Season of the Swamp, page 1

SEASON OF THE SWAMP

Also by Yuri Herrera

Ten Planets

A Silent Fury: The El Bordo Mine Fire

The Transmigration of Bodies

Signs Preceding the End of the World

Kingdom Cons

SEASON

OF THE

SWAMP

A NOVEL

YURI HERRERA

Translated from the Spanish by Lisa Dillman

Graywolf Press

La estación del pantano copyright © 2022 by Yuri Herrera

The English language translation is published by arrangement with Editorial Periférica de Libros S.L.U., c/o MB Agencia Literaria S.L.

English translation copyright © 2024 by Lisa Dillman

Part of this novel was written with support from the Awards to Louisiana Artists and Scholars.

The author and Graywolf Press have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify Graywolf Press at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Published by Graywolf Press

212 Third Avenue North, Suite 485

Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401

All rights reserved.

www.graywolfpress.org

Published in the United States of America

Printed in Canada

ISBN 978-1-64445-307-0 (cloth)

ISBN 978-1-64445-308-7 (ebook)

2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1

First Graywolf Printing, 2024

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Herrera, Yuri, 1970– author. | Dillman, Lisa, translator.

Title: Season of the swamp : a novel / Yuri Herrera ; translated from the Spanish by Lisa Dillman.

Other titles: Estacíon del pantano. English

Description: Minneapolis, Minnesota : Graywolf Press, 2024.

Indentifiers: LCCN 2024011418 (print) | LCCN 2024011419 (ebook) | ISBN 9781644453070 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781644453087 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Juárez, Benito, 1806–1872—Fiction. | Juárez, Benito, 1806–1872—Exile—Louisiana—New Orleans—Fiction. | New Orleans (La.)—History—19th century—Fiction. | LCGFT: Biographical fiction. | Alternative histories (Fiction) | Novels.

Classification: LCC PQ7298.418.E7986 E8813 2024 (print) | LCC PQ7298.418.E7986 (ebook) | DDC 863/.7—dc23/eng/20240313

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2024011418

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2024011419

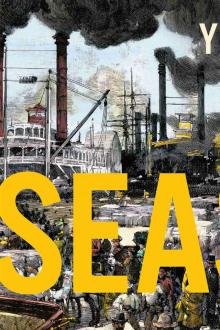

Jacket design: Carlos Esparza

Jacket art: North Wind Picture Archives / Alamy Stock Photo

1853. Benito Juárez has served as judge, deputy, and governor of the state of Oaxaca. But he has yet to become the man who will lead his country’s liberal reform, first as minister and then as president, and he is certainly not the hardheaded visionary who will lead the resistance against France’s invasion of Mexico and restore the republic. Nevertheless, he’s managed to make a number of enemies, in particular Santa Anna, who will not forgive Juárez for forbidding his entry into Oaxaca in 1847, when Santa Anna fled the capital after the disastrous war with the gringos. This is why now, back in power, Santa Anna has Juárez arrested and sent into exile.

In his autobiography, Apuntes para mis hijos (Notes for my children), Juárez describes in detail his arrest, the long journey to San Juan de Ulúa prison, and his exile to Europe via Havana, where he decides to stay and plan his return. Here, his account becomes terse. He says only:

In Havana “I remained until 18 December, when I left for New Orleans, where I arrived on the 29th day of that month.

“I lived in that city until 20 June 1855, when I headed to Acapulco to lend my services to the campaign …”

Juárez says not a word about his nearly eighteen months in New Orleans, not a single one, despite the fact that while living there he met up with other exiles, despite the fact that it is there that he evolved into the liberal leader who would transform the trajectory of his country over the decades to come. Apart from two or three vague anecdotes that appear in the multiple biographies of Juárez, no one knows what happened in New Orleans.

It is this interval, this gap, in which the following story, or history, takes place. All the information about the city, the markets that sold human beings, as well as those that sold food, the crimes committed daily and the fires set weekly, can be corroborated by historical documents. The true account of what happened, this one, cannot.

For Tori

SEASON OF THE SWAMP

ONE

The badges dragged the man from the ship, hurled him down the gangplank, and he fell in front of them and then attempted to stand, but the badges conquered him with clubs and he didn’t defend himself from their blows, because his hands were clasping a treasured object to his chest. One of the badges torturing him said Drop it. They didn’t speak the language, but that’s what the badge was saying. Drop it! shouted the one who seemed to be the boss, and then he insulted the man; they didn’t recognize the word but they recognized the language of hate. But the man did not drop it, not until three badges wrenched one arm and three wrenched the other, and the object fell to the ground and popped open, and the boss picked it up, and though he’d no doubt held objects like this one before, he was astonished to see that it was a compass.

In that frozen moment in which the badges looked at the boss and the boss looked at the compass and the man looked at the boss holding the compass and nobody knew what to do, he caught a glimpse of the tattoo on the man’s back, on his shoulder blade, a glyph of a bird walking one way while looking the other.

Then time unfroze, the boss snapped the compass shut, turned, and walked off, and his badges lifted the man up only to drag him off like a beast once more and disappear into the throng.

Then everything kicked into action: the cranes hoisting sailboats, the ships loaded with hay and coal, the cotton—so much cotton, hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of bales of cotton—the mountains of produce being unloaded, the smell of fresh produce, the smell of rotting produce, the promiscuity of incomprehensible voices, the people bustling here and there, the smell of the people bustling here and there; to the left, dark water specked with lights; ahead, the dim lights of lampposts; to the right, the twinkling lights of the city.

They let themselves lurch between the stevedores and the men who suddenly began to swarm them, offering things and pointing this way and that.

He leaned over to Pepe and shouted into his ear did he have the address. Pepe looked stricken. What was it, what was it. A hotel. Mata had sent word that he’d wait for them at a hotel. A hotel named for a city. Or a state. Or was it a person. Something with a C.

“Hotel Chicago?” he shouted into Pepe’s ear.

Pepe made squint eyes.

“Hotel Cleveland?”

Pepe dubitated, not dissenting, just dubitating.

“Hotel Cincinnati?” he asked.

Though the voices around them were a sea of unnavigable sounds, one of the squawkers accosting them beamed and, face aglow, said:

“Hotel Cincinnati,” and tapped his own chest. “Hotel Cincinnati.”

Then gestured for them to follow.

He shrugged and said to Pepe Let’s go, and the city sucked them up like a sponge.

The man walked fast but kept turning back to ensure that he and Pepe were following; after climbing down from the levee and entering the actual city-city—less congested but more mud—their guide began to walk slower and slower, until he stopped entirely, then whistled in no apparent direction, and from the alley emerged a little kid to whom he gave instructions using the universal sign for writing, and the kid took off running. Their guide turned back to them and thumbs-upped in triumph, then walked on once more.

They came to a house with a torch over the door. With a majestic flourish, their guide, spent, offered them the narrow square door as if it were the entrance to a palace. Beside it, a strip of cloth read Hotel Cincinnati.

They entered single file; inside, the boy was still holding a hammer in one hand and a strip of fabric in the other; behind him was a dark hallway, a rocker, a fireplace around which were arranged several armchairs where three sailors sat warming their hands, and an oak table where an austere woman sat, already asking Yeah, what? with her nose.

He pulled out the documents he’d shown at customs, but the woman shook an impatient head and thumbed her fingertips in the universal sign of This is what I’m talking about. So he pulled out some of the money he’d brought, in pesos, which the woman assessed for a moment before she nodded, They’re legit, took them, and gave an order to the kid, who trotted off down the hall.

They followed him to an inner courtyard containing nothing but broken chair parts and stacked-up tables, and a door at the back, which the kid opened for them. Two cots. One whole chair. A hook to hang clothes on. A pewter basin. The kid pointed to another door on another side of the patio, with any luck the toilet. The boy gazed at them in silence for a minute. Then made the universal sign of Welcome to the Hotel Cincinnati and left.

His reception on disembarking from the packet boat had been a foretaste of all that was to come: waiting and waiting and not knowing words and not being seen and learning the secret names of things.

When it was finally his turn he had pulled out his papers, but instead of taking them, the bureaucrat suppose

He’d kept his mouth shut when his papers were handed back. And Pepe had been dispatched much quicker.

They had been on their way out when the compass man landed at their feet.

A cockroach traversed the ceiling as if setting out across the desert, illuminated by a band of light coming in from the courtyard. They tracked its progress in silence even though each of them knew the other was awake. They watched it wander back and forth for a while. Then Pepe said:

“When can we go back?”

The cockroach turned and scuttled off to a corner.

“Soon, no doubt.”

They had to find the others. The next morning, he inquired as to whether Mata too was lodging there, writing out Mata’s name and mimicking the man’s long mustache. Mata was not lodging there. He asked more for the sake of it than out of any actual optimism. By this point he suspected that if the Hotel Cincinnati even existed, this was not it. But there was no point asking for the real Hotel Cincinnati, as if they might reply, Oh, you wanted the real Hotel Cincinnati.

They drank a hot drink aspiring to tea, which the austere owner logged in her little notebook, then put on their coats and set out. For a few minutes, they stood on the sidewalk in silence.

Though it was a sunny day, the street failed to register this fact. It wasn’t the worst cold he’d ever felt, but it was a slow cold that, rather than strike all at once, took its time finding just the place to let a layer of frost slip in under his coat. They walked to the corner and looked in every direction. No sign of yesterday’s crowds. They headed for the river, and as they neared it, the streets perked up: there came a smell of burning coal, shops began to open here and there, they heard whistling. A drunk, wakening to the horrific news that he was no longer drunk, looked their way with the clear intention of asking for alms, but quickly changed his mind.

Arriving at the levee, they headed to the spot where the compass man had been hurled. Somehow, he had hoped for a sign of what had happened, any sign of the beating, of the adrenaline, of the onlookers. There was nothing.

Back at the grand Hotel Cincinnati, they walked in to find two sailors bumping chests and chins right there in the, uh, lobby. The sailors spat saliva, tobacco, and insults like dogs separated by a fence, or perhaps not separated, since one leaned over all casual-like and took down the poker hanging beside the chimney, while the other—surprisingly agile, given all that hair, all that flesh, all that rum on his breath—took a step back and pulled from his armpit or who knows where a fat rope with a heavy ball on one end; he swung it around once, tracing a perfect circle, as though to furl the heat from in front of the fireplace, and the second time around he cracked the other sailor’s skull.

It was a beautifully fluid moment, despite the appalling sound the sailor’s skull made as it split. He and Pepe would come to find that such juxtapositions were quite common here.

The austere innkeeper snapped her fingers and signaled to the kid, who tugged down his cap, put on his coat, and ran off, while the husband—the one who’d guided them to the world-famous Hotel Cincinnati—pulled a pistol from under his armchair but didn’t point it at the sailor, who, though no longer swinging his weapon, was still brandishing it, bent arm aloft; the husband simply offered a couple of calm suggestions: time to stand back, put down the weapon, don’t be a jackass, one or two of those.

The sailor rolled up his weapon and tucked it back under his arm, his calm methodry in stark contrast to his endless shouting. Then the loud and living sailor bent over the collapsed one, opened his coat, and from an unusually broad pocket pulled out a pair of pants. His pants. The husband followed all this with interest but not judgment, pistol in hand, a simple fact, nothing more. Slowly, the sailor grew calm and began making comments about the man whose blood and cranial matter were now splattered about the room: that’s a shame, he was asking for it, I didn’t mean to, one or two of those.

After a few minutes the badges arrived, all slack-like, as if they’d just been dragged from a toasty-toes bath. Three of them. One sent another to examine the victim while he questioned the victimizer, who explained with his hands, mouth, pants, and weapon what he’d already said. The officer asked for the sailor’s weapon by name: slungshot. It was only then that he was actually able to appreciate the object. A round, heavy, ball-like mass at one end, covered in thin ropey fabric; the fabric was stained with blood, and not all of it was fresh: ochre specks dotted its entire circumference.

The interrogator wore an understanding expression while attending to the tale, nodding along, and seemed to side with the aggressor, tsking his head back and forth to signal What an outrage, for one man to lay a hand on another’s property. He gestured to the third officer, who wasn’t doing anything, that the man should be taken in; officer three unhitched from his pants a pair of exceedingly heavy cuffs, but officer one signaled that the cuffs weren’t necessary, and then turned to number two, who was attempting to find the victim’s pulse, and shook his head; the order-giver gave the order to haul off the corpse but showed no sign of lending his own hands, instead rubbing them together in the universal sign of Mission Accomplished, and then turned. The innkeeper’s husband took pity and helped officer three drag the victim away. A moment later, the austere innkeeper began mopping up the sanguineous intimacies smeared all over the floor.

Given that he and Pepe were witnesses, he assumed they’d be interrogated, but the officers didn’t so much as glance their way. Or rather: they glanced their way for a second, without registering them as anything other than wallpaper.

For two days they took turns guarding their meager possessions: clothes and pesos—few and suspect—a book from Havana about the United States Constitution, letters from Margarita, a few documents. One of them would go sit by the fire for a spell while the other kept watch inside the room. Who was to say thieves wouldn’t be back to strike the magnificent Hotel Cincinnati once more.

On their second day he found a newspaper. Unintelligible at first sight. Like when he’d taught high school physics and his students stared at the symbols and formulas on the chalkboard as if they were all just some kind of inhuman scrawl. Then he’d explain how each number and each symbol did something when joined together, and how the something that they did was in fact profoundly human, and his students began to glimpse a new world in those equations, the same way you see animals in the clouds, except these animals actually existed.

A few words he knew, others he intuited. He spent that second day carrying the paper back and forth between guard posts without anyone demanding it back. He was able to decipher ships’ schedules and cargos; ads for dance academies and moving companies and guesthouses (they already had a place to stay, though, at the Cincinnati, no less); news of a woman—“a lover of the arts,” the article called her—who had stolen a statue from someone’s house; a story about a Spanish ballerina, “Señorita Soto,” who’d performed several numbers never before seen outside of Spain; the arrest of a man accused of obtaining money under false pretenses (how elegant it sounded); several carriage drivers detained for furious driving (so beautifully put); a woman who had stabbed her husband; an article about Sonora, noting that it was a very rich state and that soon an expedition from California would set out to quash the Apaches (to steal Sonora, more like it, though that’s not what it said); cures for gonorrhea; rewards for runaway slaves; and an advertisement that destroyed him, for a Slave Warehouse. The ad was accompanied by a wee little drawing of a man who was supposed to be a slave, with a bundle tied to a stick over one shoulder, as if he were traveling—as if the man were doing the one thing it was utterly impossible for him to do. His eyes remained fixed on the image like it was the longest article in the paper.