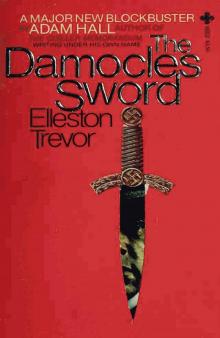

The Damocles sword - Trevor, Elleston, page 1

Playboy

paperbacks

THE DAMOCLES SWORD

Copyright © 1981 by Trevor Enterprises, Inc.

Cover photo by Swan Mosberg: Copyright © 1981 by PEI Books, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by an electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording means or otherwise without prior written permission of the author.

Published simultaneously in the United States and Canada by Playboy Paperbacks, New York, New York. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 81-82967. First edition.

Books are available at quantity discounts for promotional and industrial use. For further information, write to Premium Sales, Playboy Paperbacks, 1633 Broadway, New York, New York 10019.

ISBN: 0-872-16932-4 (U.S.)

0-867-21021-4 (Canada)

First printing February 1982.

To

Jean-Pierre

Contents

1

LONDON, JULY 1939

2

BERLIN, AUGUST 1939

3

4

LONDON, 15 AUGUST 1939

BERLIN, 16 AUGUST 1939

LONDON, 17 AUGUST

5

LONDON, 20 AUGUST 1939

6

BUCHENWALD FOREST, 26 AUGUST 1939

BERLIN, 27 AUGUST 1939

7

BERLIN, 28 AUGUST 1939

8

GERMAN-POLISH FRONTIER, 31 AUGUST 1939

BERLIN, 1 SEPTEMBER 1939

BERLIN, 3 SEPTEMBER 1939

LONDON, 3 SEPTEMBER 1939

9

BUCHENWALD, 20 SEPTEMBER 1939

10

BERLIN, 1 NOVEMBER 1939

11

BERLIN, 9 NOVEMBER 1939

12

BUCHENWALD, 12 NOVEMBER 1939

13

LOWESTOFT, ENGLAND, 15 NOVEMBER 1939

BUCHENWALD, GERMANY, 16 NOVEMBER 1939

BERLIN, 17 DECEMBER 1939

14

LEIPZIG, 10 FEBRUARY 1940

NEAR SCHWARZHEIDE, 27 FEBRUARY 1940

SACHSENHAUSEN, 3 MARCH 1940

BERLIN, 3 MARCH 1940

15

BERLIN, 5 MARCH 1940

16

BERLIN, 8 MARCH 1940

17

BERLIN, 9 MARCH 1940

ZEHDENICK, 9 MARCH 1940

18

BERLIN, 10 MARCH 1940

19

DEBNO, POLAND, 12 MARCH 1940

20

BERLIN, 12 MARCH 1940

21

BERLIN, 14 MARCH 1940

22

LONDON, 14 MARCH 1940

23

BAVARIA, 15 MARCH 1940

BERLIN, 15 MARCH 1940

NEAR SCHONEBECK, 15 MARCH 1940

24

FURSTENWALDE, 17 MARCH 1940

BERLIN, 18 MARCH 1940

SACHSENHAUSEN, 20 MARCH 1940

25

BERLIN, 21 MARCH 1940

26

LOWESTOFT, ENGLAND, 24 MARCH 1940

27

BERLIN, 24 MARCH 1940

DEBNO, POLAND, 24 MARCH 1940

28

BERLIN, 25 MARCH 1940

29

LOWESTOFT, ENGLAND, 25th MARCH 1940

30

BERLIN, 25th MARCH 1940

31

BERLIN, 25th MARCH 1940

32

DEBNO, POLAND, 26 MARCH 1940

33

BERLIN, 26 MARCH 1940

34

DEBNO, POLAND, 26 MARCH

35

BERLIN, 26 MARCH 1940

36

REGENSBURG, BAVARIA, 26 MARCH 1940

37

WURTTEMBERG, SOUTH GERMANY, 27 MARCH 1940

38

ZURICH, 28 MARCH 1940

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

1

LONDON, JULY 1939

The gates of the palace were opened at 3:15 in the afternoon, a few moments after Big Ben had ..chimed the quarter, and within twenty minutes the parking area of the forecourt was full, and traffic began flowing into Wellington Barracks. Along the Mall the police were watching for the windscreen stickers and directing the guests into parking lanes. The sunshine was hot and the air sultry and, in their summer dresses and wide floppy hats, the women were more fortunate than the men in their dark formal suits. By a quarter to four the pavements were crowded along the Mall, Birdcage Walk and Buckingham Gate. Ten thousand people had received invitations, and more than eight thousand were expected to attend.

Shortly before four o’clock a retriever was caught in the traffic jam and run over, and its squealing pierced the nerves of the people nearby until a policeman put the animal out of its misery. One woman fainted and had to be given first aid. The crowds moved on toward the palace, now hurrying.

The band of the Coldstream Guards struck up the National Anthem as the royal family appeared from the Garden Entrance promptly at four o’clock, and within a few minutes the king moved off, escorted by the Lord Chamberlain, leaving the two princesses with their mother as the presentations began. Not long afterward the guests began converging slowly on the refreshment areas, some of them to await the arrival of the king at His Majesty’s tea tent. Everyone complained of the heat, and, of course, of the international situation, though voices were lowered in the vicinity of the Diplomatic Tent. It was noticed that the German Ambassador had few people around him, and in any case seemed in no mood for light conversation.

The civil band had now taken over from the military for a while, and many of the guests found the music cheerful.

“It’s up to Mr. Chamberlain,” a lady in mauve was saying. “He’ll do it again, of course—he’s more clever than some people give him credit for.” She patted gently at the perspiration below the brim of her muslin hat, and noticed that Lady Barbara had brought that awful child again this year, the one with the whining voice. The girl wasn’t ready yet for royal occasions.

Conversation drifted across the crowded lawns, most of it desultory as the guests moved ceaselessly, trying to catch a glimpse of the royal family.

“Absolutely pathetic,” a young charg6 d’affaires was saying quietly near the Diplomatic Tent. “Every bomber was obsolete and they’re still using biplanes for fighters, except for half a dozen new ones. My host kept on apologizing to me, for some reason. The thing is, if Hitler decides to go into Poland, their air force won’t stop him.”

“Then I suppose we’ll have to.”

“We’ll have to try.”

King George moved quietly among his guests, the Lord Chamberlain introducing him to those he had not met before. He smiled for them punctiliously, though it was noticed that he looked tired, and sometimes glanced across the lawns to where the queen’s party was moving, as if he missed the comfort of her presence.

This afternoon, however, his stutter was hardly noticeable, thanks to his constant efforts to overcome it.

Over by the general tea tent a small throng had gathered, attracted by raised voices. Lady ffoulks-Barrington had fallen, valiantly trying to curtsy at the age of eighty-three. A first-aid unit of the Navy was quickly called to the spot, and the queen was seen to be upset, feeling she was herself the cause of the accident. A stretcher was brought for the fallen guest, who seemed to be in some pain, and it was a few minutes before the queen could continue to greet people with her customary charm.

The talking had more energy around the Diplomatic Tent, where the foreign contingent was dutifully awaiting the arrival of the king.

“Labour’s shouting its head off about conscription, while the Tories are all out for further appeasement to calm Hitler down. God help the Poles, that’s all I can say.”

“I think it was an act of absolute lunacy.”

“What was?”

“That pact we signed with them.”

“Oh. You may be right.”

Two men were standing alone beneath one of the trees, a colonel in uniform with Intelligence Corps insignia, and a slightly younger man in morning dress. Their heads were down as they talked quietly, and the civilian —Sir Thomas Benedict, a newly elected Member— poked at the grass with the toe of his polished black shoe. “Made an awful gaffe just now,” he said, half to himself.

“What?” Colonel Fenshaw turned his head abstractedly. He had been gazing somberly at Herr von Ribbentrop, thinking what a clown he looked in that big top hat.

“I said I made an awful gaffe,” Sir Thomas told him again. “Bumped into Harris just now—you remember his boy was killed on a motorbike a few months ago?

By way of condolence I said well, at least the boy wouldn’t be sacrificed in this senseless war that’s coming. Then I remembered he’s got another son, of military age. Damned stupid of me.” He jabbed rather hard at the grass with his toe.

“He knew you meant well,” the Colonel told him. “Think so?” Sir Thomas felt slightly better; he’d been depressed all day as it was, with the news coming in, and Vanessa over there in Berlin making eyes at that bloody Jack-in-a-box. He hesitated for a moment before speaking again. “Something you might do for me, Brian, if you will.”

“Anything you say.”

“The king telephoned me yesterday, about my daughter.”

“Vanessa?”

“Yes. What he said was that I ought to persuade her

“Quite so.” Colonel Fenshaw gazed across the lawns to where the king’s party was moving. His commanding officer, General Westerby, had brought up the matter of “the Benedict girl” a couple of days ago at the club, saying that more than a few people in high places were becoming embarrassed. The Benedicts were close friends of the royal family and Sir Thomas had become an important figure in the House, and it was common knowledge that his daughter had been following Hitler about for months, and that the astute Reichschancellor had taken pains to encourage her attentions. He didn’t want a war with England, and Vanessa Benedict might prove useful as an intermediary behind the scenes.

“You want me to send Martin over there?” Fenshaw asked after a moment.

Sir Thomas looked up quickly, relieved. “Yes. Of course, I’ve asked him to go and bring his sister back, more than once, but as he says himself, she’s pretty strong-willed. But if you sent him to Berlin officially, with orders to bring her back, it might do the trick.” The Colonel thought about it, watching the colors of the uniforms and the women’s dresses flowing across the lawns. “Orders are one thing,” he said doubtfully. “She’s a free woman, after all.”

“Martin would do his level best to persuade her, if you gave him official sanction. I’m his father, but you’re his commanding officer. There’s a difference.”

They began strolling across to His Majesty’s tea tent, so as to be there when the king arrived. “I’ll have to talk to General Westerby first,” Fenshaw said. “This isn’t really an Intelligence matter.”

“But you think he might agree?”

Fenshaw reflected. “We’d be doing the Palace a favor. That’s going to carry weight, when I put it to him. Give me a few days, and meanwhile we should keep this strictly confidential.”

2

BERLIN, AUGUST 1939

Outside the Reichschancellory the massed crimson banners hung limp in the evening air, their colors deepening as the floodlights took over from the dying glow of the sunset. Pigeons dipped and wheeled above the stone frescoes, sometimes swooping past the lower floors of the building, their wings spread wide and seeming motionless, gilded by the lights. The ground-floor windows were radiant, and passers-by could see the brilliance of the chandeliers inside.

The vast Hall of the Ambassadors was already crowded, bedecked with uniforms and the silk and satin gowns of the women, their colors complementing the rich blooms of roses and hydrangeas under the grouped spotlights. Shortly before eight o’clock the great doors at the far end of the hall were swung open, and suddenly the Reichschancellor was among his guests, already shaking hands with those at the head of the lines.

The drone of conversation had dropped to near silence as the doors had opened; now the hall was filled with a low and vibrant murmuring, as if the Chancellor, simply by his presence, had commanded a change of mood in the spirit of the people. The men in uniform had stiffened suddenly, and the women had leaned forward a little toward the single figure, their eyes eager and their lips parting as they waited, their breath coming faster.

“Oh, I can’t see! Is he there yet?”

“Shhh . . . yes, darling.”

‘The Führer?”

“Yes. The Führer.”

“Oh . . . will he shake hands with me?”

“He’s going to shake hands with all of us, but only if we keep very quiet.”

In a moment a low booming laugh sounded above the murmuring, and someone said, “That’s Field Marshal Göring.”

A few of the women laughed lightly, their nervousness allayed; things would be less solemn with Göring here: he was always so jolly.

A girl in a turquoise sequined gown dropped her fan, and it clattered on the marble; heads turned, and her face was crimson when she straightened up from retrieving it, too embarrassed to notice that several of the personal SS guards had lifted their heads sharply at the sound.

A short bearded man in coattails, newly arrived from Geneva, was whispering. “That is Himmler over there, yes?”

“Yes.”

“And just behind him—the tall blond man?” “Heydrich.”

“My God, the power that is here tonight . . .” “What? Oh, yes. They are powerful men.”

Not far from the head of the lines stood Vanessa Benedict, rather tall, a little gawky in her ivory satin dress, devoid of jewels but with her wide eyes shining as she stared at the Reichschancellor.

“Don’t you see it?” she asked the man beside her in a low, intense whisper. “Don’t you feel it in here?” She darted a look around her, but only for an instant before her eyes were drawn irresistibly back to Adolf Hitler. “Can’t you sense the excitement in here, the pride?”

“Yes,” her brother said.

“Doesn’t it make you want to yell out Heil! at the top of your voice?”

“Frankly, no. I’m more used to ‘God Save the King.’ ”

“Oh, Martin . . . you’re so English!”

“We both are, actually.”

She stopped talking now; the Chancellor was only a few yards away. Martin could feel the excitement in her, shaking her like a fever as she watched the short man in the simple uniform greeting the guests. Vanessa had always been a lively girl, buzzing with new ideas and ready to shout their praises from the housetops; but he had never seen her like this, quivering with tension, her hands locked together in their long white gloves, her eyes shimmering as she waited for Hitler to approach, as if she waited for a lover. Martin had noticed this in some of the other women present.

Suddenly she was taking a step forward and saying, “Good evening, my Führer,” as the man took her slender gloved hand in his, bowing slightly and offering his thin smile.

“Vanessa, my dear young lady . . . I’m so glad you could come.”

“I am always at your command, my Führer. Always.” She turned quickly. “Let me present my brother, Martin.” With a soft ring of triumph she said, ‘The Reichschancellor . .

Martin noted that they both used the familiar “thou” to each other, but the thought slipped from his mind as he returned the dark penetrating gaze of the man in front of him. As they shook hands he felt a sudden tension in the air, as if all the deep half-muted excitement in this enormous room had become focused here. Unnerved, he heard himself saying in German, “A privilege, Herr Reichschancellor.”

“Your sister has talked about you a great deal, Herr Benedict. Welcome to Berlin.”

Martin was aware of brief impressions: a faint smell of carbolic soap, or perhaps hair pomade ... a sense of raw energy, though not in the handshake or in any physical way—it was like a dark force vibrating, its violence held in check.

Vanessa was taking her brother’s arm affectionately. “I rather suspect he’s here to take me back to London, but of course I’m not going to let him!” She laughed easily, but Hitler looked quite put out.