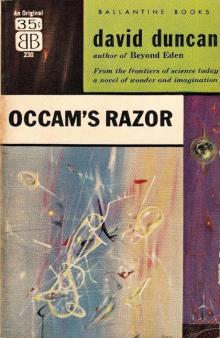

Occam's Razor - David Duncan, page 1

“The voice from the receiver was Roger Staghorn’s, shaking and shrill with tension. ‘Hume!’ it cried. ’At my laboratory! For God’s sake get over here quick!’ Before he could answer there was a clattering sound as though Staghorn had dropped the receiver. Shouts brought no reply. Hume heard only what sounded like a distant splashing.

“No more than three or four minutes could have passed from the time of the phone call until Hume pulled up at the curb beside the electronics building, but there was no light coming from the basement windows. He ran down the steps and opened the door Staghorn was so proud of leaving unlocked. Then he paused, peering into the interior darkness. ‘Roger?’ he called. ‘Roger?’ There was no answer. The basement was like a tomb, and filled with a clammy dampness rising from the big basin of bubble solution. Not a sound.

“He set his emergency kit on the floor and struck a match. In the darkness the tiny flame blinded him and before he could see anything, a puff of breeze blew it out. Behind him the door creaked open and enlarged the rectangle of dim light coming in from the night. At the same time, Hume heard a splashing sound, then a quick pattering on the concrete floor. For an instant or so, two figures silhouetted in the doorway. He could tell no more than that the shapes looked human.”

By David Duncan

Remember the Shadows

The Shade of Time

The Bramble Bush

The Madrone Tree

None But My Foe

The Serpent’s Egg

Wives and Husbands

Dark Dominion *

Beyond Eden The*

Trumpet of God *

Occam’s Razor *

*Published by Ballantine Books, Inc.

This is an original novel—not a reprint—published by Ballantine Books, Inc.

david duncan

OCCAM’S RAZOR

Ballantine Books • New York

©, 1957, by David Duncan

Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 57-13096

Printed in the United States of America

Ballantine Books, Inc.

101 Fifth Avenue, New York 3, N. Y,

For Ellice and Dan

1

At eight o’clock on the evening of February 17 Cameron Hume left the medical center of the Santa Felicia Island base and drove his jeep to the auditorium to hear Dr. Roger Staghorn lecture to a group of young naval officers on the mathematical theory of minimals. A sultry breeze swept through the night. Overhead the sky was filled with ragged blue-black clouds shot through with a lace of moonlight, and as they twisted across the sky the moon itself occasionally soared into the clear between the rifts. A first-quarter moon, beautiful from earth. But a dead thing in space, a dead goal. Hume didn’t think anyone was going to reach it—an improper thought under the circumstances but one he couldn’t deny.

It was going to rain tonight. This was supposedly the dry season but that meant only that it rained less often than during the wet season, and tonight it would rain. He could smell it. He could hear the surf rubbing the rocks around on the long shingle beach, a whispering sound punctuated by hollow blockings as though unseen guests were asking to be let in. They wouldn’t be—not on Santa Felicia Island. It was a night to make one dream of love and poetry but no one was doing much dreaming of that kind. The nature of the night was a menace. It meant another twenty-four hours’ delay in the launching of the Luna One, and at any time during those twenty-four hours the world might explode. Meanwhile every radar station was in constant operation; the sonic ears were listening far beneath the surface of the surrounding ocean, and the fleet of deadly Homing Pigeons was set to scream into the air at the flicker of a vacuum tube. Under these conditions men attempted to perform their duties as usual and pretend that life and its problems were of some consequence.

Hume pretended this successfully as he drove to the auditorium. He was interested in Staghorn and he was interested in what Staghorn had to say about minimals. The lecture was to deal with physical subject matter but Cameron Hume felt that the principles involved might also have a psychological application. As the officer in charge of the hospital and as a psychiatrist, it was his duty to be interested in such matters. Besides, he’d been concerned lately with the mental state of Roger Staghorn. Not that Roger’s trouble would have been serious elsewhere; on Santa Felicia any kind of trouble was serious.

So it was startling, and for a moment confirming, to step into the little conference room where Staghorn was giving his lecture and find him blowing a soap bubble. The place was dark when Hume opened the door and let in a flood of light from the hallway. Staghorn sat at the speaker’s table on the opposite side of the room, and without taking his eyes from the bubble he called out, “Shut the door, damn you, whoever you are!”

Hume shut the door without identifying himself and groped forward to a chair beside Captain Flanders. He could see better by then and realized that the soap bubble was part of a demonstration. The conference table was covered with an electric blanket that provided an upward current of warm air to keep the bubble suspended. Staghorn sat behind the table, and in front of it, their chairs pulled close so they could watch, sat a dozen young naval officers. Captain Flanders, Hume and several civilian scientists sat behind them.

The bubble, about a foot in diameter, had been filled with gas from a small pressure tank and now floated magically above the table. Staghorn held an insulated metal rod in each hand and brought them forward on either side of the bubble. Then with his foot he pressed a switch beneath the table to put charges on the rods. Instantly the bubble began to glow with a pale blue light of its own, a light that fluctuated in intensity as Staghorn varied the distances of his two electrodes. For several seconds the bubble wavered there, its light forming dual reflections in Staghorn’s thick-lensed glasses. Then it burst, the light vanished and Hume felt a few drops of moisture flick against his forehead. Staghorn reached to the wall behind him and switched on the room lights. At Hume’s side Captain Flanders nodded a grudging satisfaction.

“A beautiful demonstration, Staghorn,” he said. “You may have invented the potential at least for a new signaling device.”

The words were intended as a compliment and anyone except Roger Staghorn would have accepted them as such. Instead he was irritated and took no pains to hide it. “I don’t invent things, Captain,” he said coldly. “If you can think of a practical application, you’re welcome to it.”

Flanders flushed angrily so that red mottles showed on his weathered cheeks. He was a small, hard man in his late fifties. “Sorry I suggested such an indecency.” His voice was a barely audible growl but Staghorn heard him.

“You should be,” he replied gracelessly.

Staghorn was a very tall individual, only four inches shy of seven feet, very lean, hollow-cheeked and pallid. His shoulders drooped forward whether he was sitting or standing, and his eyes were huge and cadaverous behind the magnification of his glasses. His dark suit had needed pressing for as long as Hume had known him. His tie was askew and he could have used a haircut. In addition to being physically untidy he had a superior and insulting manner that was particularly marked when he was in the presence of any higher authority. He was, in fact, the rudest man Cameron Hume had ever known, and Hume had reason to know him well because for the last two months Staghorn had been spending an hour a week in Hume’s private office in an attempt to improve his personality. So far the results were a poor recommendation for his doctor, but the effort had tempered Hume’s feelings toward him. No one else, however, knew that Staghorn was making the effort. “If this gets out, I’ll break your neck,” he’d said to Hume.

“Let’s just rely on ethics, Roger,” Hume told him.

Staghorn was on the island for only one reason. He possessed that certain type of genius which during the atomic age had become indispensable for the efficient destruction of mankind. He knew his value and in the privacy of Hume’s office deplored it. But at the moment he wasn’t in Hume’s office.

His bubble gone from above the table, he removed the electrical apparatus, dabbled his long pasty fingers in a basin of soap solution and wiped them on his handkerchief as though literally cleansing himself of such childish nonsense. The he placed a wooden box on the table, opened it and took out an assortment of forms, each made entirely of fine brass wire. He had cones, cubes, spirals, catenaries, interlocking circles and a variety of cycloid curves, all shaped in wire. He also took out a pair of pliers and a small silver ice pick with a needle-sharp point. Then he ignited the flame of a Bunsen burner. While he was about it, he addressed his audience.

“You’re here to learn something about minimals,” he said. “Minimal surfaces, minimal distances, minimal time and minimal energy. All are included under one general principle which in honor of William of Occam I’ll call the principle of universal parsimony.”

“Who’s William of Occam?” asked Ensign Waters.

’Tour grammar is wretched,” Staghorn said. “The past tense is proper for that question. And since he’s dead, let’s ignore the question and stick to the principle of parsimony. There are limitless applications in every field of science and, as Ensign Waters’ question shows, even in the field of education. The least effort sufficient to gain the barely acceptable end.”

Ensign Waters squirmed in his chair and plucked nervously at his protruding lower lip. Staghorn meanwhile picked up a wire with a circular loop at one end and dipped the loop into the basin of soap solution. When he lift

“The problem,” he said, “is to determine the smallest possible surface that will completely span the area enclosed by the circle of wire. Here is the visual solution to the problem. The film of soap, being controlled by the principle of parsimony, immediately assumes that shape which will fulfill the requirements with the least use of space and energy. This is the minimal surface enclosed by a circle—in this simple example, its area. Clear?”

Ensign Waters cleared his throat nervously. “Not quite. If you’ll forgive my stupidity, where’s the energy?”

“The energy is not conditional upon my forgiving your stupidity,” said Staghorn. “It consists of the surface tension of the soap film. If the film is now distorted by an external force, the principle of parsimony will force it to seek a new minimal form.” With this he brought the loop of wire close to his lips and blew gently. The film of soap billowed out, broke free and drifted away as a soap bubble. “The sphere,” said Staghorn. “The geometrical form enclosing the most space in the least surface area. You will recognize this particular bit of apparatus as a common child’s toy. I mention this to encourage those of you who might wish to pursue the subject further in your spare time. The more complicated apparatus you will have to manufacture for yourselves.” He tossed aside the circle and picked up a system of wire shaped to the outline of a cube. “Here the problem is identical in principle to the first but has a more intricate solution. What are the minimal surfaces which will unite all the extreme dimensions of a cube?” He used the pliers to straighten one of the wires, then lowered the cubic frame into the basin and carefully withdrew it. Soap films now formed indented pyramids on each of the six sides of the cube, their apexes meeting at a small square of film near the center.

“Again the soap film gives the answer,” said Staghorn. “Here it is.” And he held the system of glistening surfaces out for their inspection.

“But what is the area?” asked Ensign Waters doggedly. “You’re looking at it,” snapped Staghorn.

“Sure, but that doesn’t tell me how many square centimeters it is.”

Staghorn leaned across the table and spoke with exaggerated patience. “Any solution you reached by mathematical computation would be nothing except an abstraction of what you see before you in reality. I’m trying to impress upon you that all mathematical abstractions, if valid, must relate to reality. But if you have the reality, why must you also have the abstraction?”

Bryan Waters thrust out his jaw at Staghorn. “Because when I’m back at my desk or on duty in the cage, I work with mathematical formulas, not soap film. When I compute the minimal path of a guided missile, I want to know what I’m doing!”

“I assure you,” said Staghorn, “that anyone who computes the path of a guided missile can’t possibly know what he’s doing.”

His voice was loaded with sarcasm. At Hume’s side Captain Flanders struck his palm angrily against the arm of his chair. “Just one minute,” he said. “Waters has a point, damn it. You’re here to instruct these boys, Staghorn, and I expect you to answer their questions and do it so that they can understand you.”

Staghorn shifted his attention to Flanders and picked up the silver ice pick. For an instant Hume thought he was going to hurl it at Flanders’ breast, but instead he used it as a pointer to count the number of plane film surfaces arranged within the wire cube. There were thirteen of them. “I trust none of you are superstitious,” he said. “I’ve heard that sailors are often afflicted in that respect.” He heated the tip of the ice pick in the flame of the Bunsen burner and touched it to one of the films. The film instantly broke and vanished. “Note now,” said Staghorn, “how the remaining surfaces have automatically readjusted themselves to the minimal area connecting the sides to which they still adhere. Although the sides of the cube are straight, the major surface is now a curve.” He touched this with the heated ice pick and it too vanished. Then he carefully put the apparatus aside and faced Flanders. “And now, if I may be permitted to get Ensign Waters out of his quandary without exciting the wrath of the Base Commander, I shall explain that there are certain minimal surfaces or minimal distances, connecting an infinite number of points, where mathematics based upon the calculus of variations is helpless. In such cases Ensign Waters could calculate from now to eternity without arriving at a solution subject to proof. And yet the solution exists in reality and can be demonstrated visually in soap film. Here is an example.”

He searched among the wire frames in his wooden box and brought out one of extremely curious design. Hume had an uneasy feeling as Staghorn held it out, suspended by a fine thread, and let it turn slowly in front of the group. Parts of it kept seeming to vanish and reappear in a manner vaguely reminiscent of the stripes on a rotating barber’s pole. It might easily have won an award at an exhibit of modern art.

Staghorn continued his lecture. “Here we have the framework of two systems, in each of which a single onesided Moebius surface encloses a three-dimensional space. The two systems are interlocked in such a way that the enclosed spaces are interpenetrating by a constantly varying amount. In reality an infinite number of such systems could be interlocked, but two are enough to illustrate the principle. Mathematical proof of what constitutes the minimal connecting surface is impossible. None the less these surfaces exist in fact and can be shown in soap film.” Slowly he lowered the wire figure into his basin and withdrew it. What looked like dozens of soap films now stretched between the wires, glimmering softly in the light and enclosing a twisted volume of space that the eye couldn’t follow.

Looking at it, Hume had a nostalgic memory of sitting at his mother’s dressing table when he was about eight years old and pulling the two side-wing mirrors forward until his head was enclosed by a triangle of mirrors. Then he’d sit for a long while, looking at the hundreds of reflections that surrounded him at increasingly dusky distances—some in profile, some straight on, some from the back. He could never be quite sure that it was the back of his own head he was seeing. That was such an impossible thing to do. It seemed more reasonable to imagine that the reflection of the boy with his back turned was someone else who might at any instant turn about and face him. It never happened, but he used to frighten himself with the thought. And he remembered the endless rooms and countless doorways that were barely visible through the opening between the mirrors, which couldn’t be folded quite together because of his neck. The path of the reflected light was a minimal too. Staghorn had just said so. Hume’s attention came back to the twisting system of soap films that dangled from Staghorn’s hand. It was a jewel of many curving facets, a jewel with a lifetime of only a few seconds. While these seconds were ticking away, Staghorn addressed Ensign Waters.

“How many separate surfaces do you see here?”

“More than I can count,” Waters replied defiantly.

“Then you can’t count very far. There are two, One surface for each system. I’ll ask you to prove it. Come. Take the ice pick.”

Reluctantly Waters stood up, bent across the table and grasped the ice pick, looking uneasily at the suspended film system.

“Only the individual soap film that you prick will break,” said Staghorn. “If there are more than two surfaces, it will take more than two pricks of the ice pick to break them. But I say that two will be sufficient no matter where you start. Heat the pick and go ahead.” Waters stared at the figure so long that Staghorn had to repeat his order. “Go ahead! In a moment the films will break because of evaporation.”

Hume leaned forward to watch as Waters passed the pick through the flame of the burner and brought its point against a transparent surface of soap film. The surface at this point snapped and vanished, but in a peculiar way the total amount of film didn’t seem to be reduced. Rather it appeared to slide over the wires into a new position. Hume would have thought this was what was expected if he hadn’t glanced at Staghorn’s face. Staghorn’s jaw dropped and his long neck shot forward to bring his eyes closer to the film system. His voice went hoarse. “Now the other one. Prick the other film. Quick!”