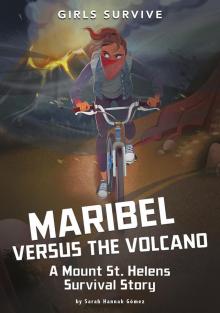

Maribel Versus the Volcano, page 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

A Note from the Author

Making Connections

Glossary

About the Author

Copyright

Back Cover

CHAPTER ONE

Cougar Junior High

Cougar, Washington

March 20, 1980

3:40 p.m.

“Thanks a lot, Maribel! Because of you, I have to wait until tomorrow to pick up my pictures!” my sister, Lupe, snapped as we walked down the hallway at school. “Why did you have to get in trouble again?”

I looked at my watch. “It’s only three-forty. That’s plenty of time to make it to the photo store.”

Lupe shook her head. “We missed the bus because you had to stay after class,” she said. “Now we have to call Mom and wait for her to pick us up. By the time we get there, the store will be closed.”

I sighed. It wasn’t like I had stayed after class on purpose. But after the fourth time my teacher, Mr. Jennings, had called on me in social studies with no response—“Miss Reyes, are you listening?”—he’d gotten mad.

He’d told me to come to his classroom after school so we could talk about “my continued failure to stay focused on course content.” That basically meant I had a bad habit of daydreaming during class.

As my older sister, Lupe always waited for me so we could catch the bus together after school. Seventh and eighth grades had different lunch periods, though, so I hadn’t been able to warn her that I would be out late.

So now I was in trouble with my social studies teacher and my sister. And when we got home and Lupe told my parents why we had missed the bus, I would be in trouble with them too.

I didn’t daydream in class on purpose. It was just that a teacher would say something, and that would make me think of something I had seen on television or read in a book. That would remind me of something that had happened at lunch the day before and… before I knew it, everyone in class was looking at me because I had no idea what was going on.

I wasn’t trying to be disrespectful to my teachers. It just sort of happened.

“Well,” I said, “it’s only Thursday. You’ll be able to go pick up your pictures tomorrow.”

Lupe glared at me. “I wanted my photos today. I was going to show them to Ms. Ybarra tomorrow.”

“I’ll make it up to you,” I promised.

I didn’t know how I would do that, but I really was sorry. Lupe loved photography. She went to the photo store nearly every week to have film developed. My parents even joked about building her a darkroom so she could develop photos herself. But our nana, who had lived with us since I was a baby, put her foot down. She said that if we wanted to have that many chemicals in the house, she would move out.

I was pretty sure she was exaggerating, but it was enough to make Mami and Dad change their minds.

Lupe and I were still bickering when we reached my locker. I spun the dial on the combination lock silently while my sister chewed me out.

“OK,” I said, stashing my books. “Let’s go.”

I slammed my locker door, and suddenly I was on my back on the floor.

I couldn’t get up. The floor was moving beneath me. The row of lockers above me rattled. I tried to look for my sister, but my eyes wouldn’t focus.

And then, just like that, everything was still—too still. It was like the world had gone from off the rails to moving backward in slow motion.

Once my gaze settled, I could see Lupe. She was on the floor, braced against the lockers. Her mouth was wide open, and the color had drained from her face.

I looked past her. At the end of the empty hallway, just before the double doors, the narrow glass case that held school trophies for sports and other events was wobbling dramatically. As I watched, it stopped its wobbling and tipped over.

Crash! It fell to the ground. The glass shattered.

I jolted. I felt as unsteady as the trophy case.

“What was that?” Lupe whispered. She tried to gulp in some air, but I heard a wheeze.

Lupe didn’t like to draw attention to it—or herself—but she had asthma. When she was stressed out or angry—like she’d been with me today—her lungs acted up.

“You felt it too?” I asked. It was almost a relief to know I hadn’t just slammed the locker shut with too much force and knocked myself over.

“Of course I felt it.” Lupe wheezed again.

She pushed herself up to standing, then held her hand out and helped me to my feet. I still felt shaky, even though the world around me had stopped moving.

Just then a classroom door opened behind us. “What was that?” a voice gasped.

I turned and saw Ms. Ybarra, the art teacher—and Lupe’s favorite person in the whole world, it seemed. When she saw us, Ms. Ybarra’s eyes widened in concern.

“Oh, girls, are you OK?” She rushed over to check on us.

“We’re OK,” Lupe said.

“What was that?” I asked. “An earthquake?”

Ms. Ybarra nodded. “A big one, I think. I’m glad you two weren’t standing near anything heavy.”

Lupe pointed to the shattered trophy case. “Luckily we missed that,” she said.

Ms. Ybarra walked over to inspect the mess. “I’ll have to call the custodian to clean it up so nobody steps on any of the glass,” she said. She turned back to us. “What are you two still doing here? There aren’t any after-school activities today.”

“We missed the bus,” I said. Lupe poked me in the side. “Well, I missed the bus. And Lupe waited for me, so she missed it too. We were going to call our mom for a ride.” I looked at my sister. “Or maybe we can just walk home. It’s only about three miles.”

Ms. Ybarra shook her head. “Oh, no, no, no. Not after an earthquake like that. I’ll drive you girls. I would never forgive myself if something happened while you two were on your own. Your parents wouldn’t forgive me, either. Come with me.”

Lupe and I followed Ms. Ybarra to the office to radio the custodian, then to the teachers’ parking lot. She had given Lupe rides home after art club, but I had never been in her car before.

A teacher’s car! I thought as we approached the little red hatchback. It seemed forbidden and almost unnatural, as if I shouldn’t know that teachers had lives outside of school.

As we turned out of the school parking lot, Ms. Ybarra rapped her knuckles on the car window. She gestured to the gigantic mountain peak—the major landmark in Cougar, Washington, where we lived—visible against the blue sky.

“Take a look at Lawetlat’la,” she said with a nod. “I think we’ve found the culprit behind our earthquake.”

I craned my neck to see. “What’s that?” I asked. “All I see is Mount St. Helens.”

Lawetlat’la is the mountain’s real name,” Ms. Ybarra said. “It’s the name the Cowlitz people gave it long before Europeans came here and renamed it Mount St. Helens. I’m surprised you haven’t learned that from Mr. Jennings.”

I was too. Then again, maybe I’d just missed it—although I didn’t want to tell Ms. Ybarra that. I was already in enough trouble for daydreaming.

“You students should know all of Washington history, not just the American part,” Ms. Ybarra continued. “You have classmates who are Cowlitz. They may not have a reservation, but this is still their ancestral land.”

“Lawetlat’la,” Lupe said slowly. “Is that why one of the hiking trails is called Loowit? And Loowit Falls? Are they related?”

“Yes!” Ms. Ybarra said. “And if memory serves me, I believe the word Lawetlat’la means ‘the Smoker.’ Seems appropriate, huh?” She gestured to the mountain again.

I stared out the window—Ms. Ybarra was right. The mountain wasn’t just a mountain. Everyone knew it had been a volcano in the past, but I had never seen it like this. Heavy clouds of smoke were pouring out of it like steam from a teakettle.

I thought of my nana’s teakettle at home and how it would shriek and sing when the water came to a boil. If I were close to the summit of the mountain, would I hear it make noise, or was it silent? When volcanoes erupted, did they fill the summit like a mug of tea with a tea bag, or did they pour out and spill over everything?

CHAPTER TWO

Swift Reservoir

Mount St. Helens

April 30, 1980

12:30 p.m.

“Hey, Maribel! Catch!” Before I could react, a Frisbee whizzed past me. It bounced on the grass of the picnic area where my family and I, along with many others, were spending the day.

I looked up to see who had thrown the disc. It wasn’t Lupe. She was sitting on the grass right next to me, fiddling with her camera.

But I saw Marcus Johnson, the son of one of my mom’s coworkers, coming from the parking lot and waving at me. Our parents were good friends, and we had invited the Johnsons out to the mountain for

a picnic at one of the

“Hi, Marcus!” I said.

I went to retrieve the Frisbee, gripped it close to my chest, and then sent it spiraling back to him. But the person who caught it wasn’t Marcus—it was his dad, who quickly sent it back. I had to leap to catch it.

I held off on returning it right away. Marcus’s mother was behind them. She was holding a picnic basket in one hand and a tote bag bursting with blankets in the other.

“Hi, Mr. and Mrs. Johnson!” I said.

I hurried over and took Mrs. Johnson’s picnic basket, setting it down next to my family’s. We had staked out a good spot at the lookout point. It was one of our favorite places for picnics—only twenty minutes away from home—but it was our first time being there since the earthquake.

There had been countless tiny earthquakes since then. I had almost come to expect them. I felt like I was constantly waiting to trip over nothing or to see pictures askew on the wall—there was something quirky to expect every day.

Many of my classmates had been out to see “the Smoker” up close in the past couple weeks. Lupe and I had begged our parents until they finally agreed to a picnic.

Now that we were here, it was unlike anything I had ever seen before. The mountain had grown in size and changed shape over the past few weeks, developing a bulge on its side. It was almost as if it was growing another mountain inside it.

Who needs a classroom science experiment when you can watch a life-size mountain burp steam and ash into the air? I thought.

Lots of other people clearly had the same idea. The lookout point was crowded today. There were babies in strollers, scientists taking measurements and photographs, hikers consulting maps, and families picnicking on blankets.

“We’re living history!” Dad had told us when we first arrived.

After the Johnsons had set up their picnic, Marcus asked me to throw him the Frisbee.

“Go over there, away from all the people,” said Mrs. Johnson. She pointed to a patch of land in the shadow of a line of trees. “See if any of the other kids want to join you!”

Marcus was already rounding up some of the classmates of ours he had found. I went over to my sister and tugged her arm.

“Come on, Lupe,” I said. “Put down your camera and play Frisbee with us.”

Lupe sighed and carefully put the lens cap on the camera. “Nana,” she said to our grandmother, “will you make sure nothing happens to my camera?”

“Of course, m’ija, Nana said, looking up from dipping a chip into a container of salsa. She held her hand out, and Lupe handed over the camera. “Don’t forget to take your inhaler,” Nana added.

Lupe blushed and ducked her head, but she obediently reached into the camera bag she had brought with her. A moment later, she pulled out her asthma inhaler. Glancing around to make sure no one was watching, she took a big puff of air in. Then she hurriedly stuffed the inhaler back into the bag.

I shook my head. My sister was so ashamed of her inhaler. It was as if she thought it made her weak or uncool to have asthma. She was always trying to sneak her inhaler out of her schoolbag and leave it at home whenever we went somewhere. It didn’t make sense to me.

Why be embarrassed of something you can’t control? I always thought.

Lupe, Marcus, and I played Frisbee with other neighborhood kids until our parents called us to eat lunch. Everything was calm for awhile. But then, when we were eating the cookies Mrs. Johnson had baked for dessert, a massive boom! shook the air.

My head jerked straight up. Everybody at the lookout point seemed to jump about a mile. It sounded like the loudest jet engine of all time. I felt the earth shake beneath my feet, just like it had at school a month ago. The vibration went all the way up my body.

High above us, Mount St. Helens had puffed out a particularly large cloud of steam. I could see ash slowly raining down. It reminded me of how fireworks looked as they died out and dropped from the sky.

“OK, kids!” my dad called. “We’re going to pack it in. Looks like Mount St. Helens is not happy we all decided to visit today.”

I sighed and turned to Marcus and the other kids we’d been playing with. “See you at school,” I said.

“Bye,” Marcus replied sadly. “See you later, Mr. and Mrs. Reyes,” he called to my parents.

So much for a fun Sunday, I thought as Lupe and I helped our parents and grandma carry our things to the car.

We headed home, but things didn’t get any calmer as we drove to our house. On nearly every block, it seemed, there were police cruisers and park ranger cars. People in uniforms were walking up and down the sidewalks and standing on porches.

“What’s going on?” I asked as I looked out the window.

Mami didn’t slow the car down, but Dad answered. “I don’t know. You’d almost think we were in some kind of cop show.”

“I don’t like the look of this,” Nana said.

“Me neither,” Mami agreed.

Thankfully there were no cars on our street when we arrived home, so we unpacked our picnic things and went inside. Lupe and I headed upstairs to finish our homework. I hadn’t done more than a few questions on my practice math quiz when I heard the doorbell ring.

Nana must have opened the door, because I heard her calling for my father in Spanish, asking him to come to the door and translate. Nana spoke English almost perfectly, but sometimes she liked to pretend otherwise—usually when she didn’t like what she was hearing or the person talking.

From upstairs I heard my parents both make their way to the front door. All of a sudden, I had a bad feeling in my chest. When I looked up from my homework and across the hallway at my sister’s bedroom, she was looking straight back at me. I knew we were thinking the same thing:

Something is wrong.

Lupe and I slid out of our chairs and quietly crept toward the stairs. From there we had a view of the door but couldn’t see who stood outside it.

“That’s ridiculous,” Dad was saying. “We were just there. Not safe to be right there at the base of the mountain, sure. But an eruption?”

“There’s no way,” Mami added.

Lupe nodded to me, and we walked downstairs. I was no longer worried about interrupting. I needed to know what was going on.

Nana saw us and motioned for Lupe and me to join the adults at the door. Dad and Mami were talking to a police officer. When he saw us approach, the officer nodded his head at us.

“Good evening, young ladies,” he said. “I’m sorry to bother you like this. I’m sure you’re just getting ready for bed.”

“Bed?” I said. “We’re not babies. It’s only six. We haven’t even had dinner yet!”

Mami shook her head at me, as if to say, Not now, Maribel.

“I’m afraid dinner is going to have to be at a friend’s or out at a restaurant tonight,” the policeman said.

“What are you talking about?” Lupe demanded. “We never go out to eat on a school night.”

Dad sighed and held up his hand. “Apparently tonight we will.”

“Why?” I asked, still confused.

“Because,” said the police officer, “you’re being evacuated.”

CHAPTER THREE

Cougar, Washington

April 30, 1980

6:02 p.m.

“Evacuated? What do you mean, ‘evacuated’?”

Mami turned to look at us. “Apparently we live in what they’re calling the red zone,” she explained. “The police are evacuating everyone who lives within twelve miles of the volcano. That includes us here in Cougar. They think it’s going to erupt.”

“When?” Lupe asked.

“Any minute now, this man says,” Dad said.

The police officer cleared his throat. “Not any minute as in tonight, he said. “But very likely in

the near future. We think. I’m not really a scientist, you know. I can’t tell you a precise date. But we’re doing this for your safety. You and all of your neighbors.”

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. First, earthquake after earthquake. Now this.

If it it’s just steam escaping from the mountain, why is everyone so worried? I wondered. It’s not like we live right at the foot of Mount St. Helens.