Glamour Ghoul, page 1

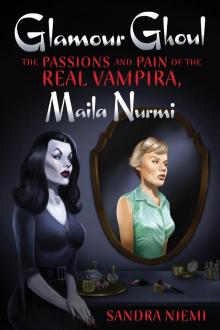

Glamour Ghoul: The Passions and Pain of the Real Vampira, Maila Nurmi

© 2021 Sandra Niemi

Published by Feral House, Inc.

All Rights Reserved

eISBN: 9781627311069

Cover illustration by Mark Hammermeister.

Back cover photo courtesy of the Jove de Renzy collection.

Feral House

1240 W. Sims Way Suite 124

Port Townsend, WA 98368

FERALHOUSE.COM

Glamour Ghoul

THE PASSIONS AND PAIN OF THE REAL VAMPIRA,

Maila Nurmi

SANDRA NIEMI

This book is dedicated to my cousin, David Putter.

Found, at last.

To my family, Amy, Noelle, Liam. David and Judi.

I love you more.

Table of Contents

Foreword

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Bring on the empty hearses that I may people them with my enemies.

Isn’t that, after all, why people commit autobiography? To aggrandize themselves and to destroy their enemies?

In any case, of course, the enemy shall be felled quite accidentally as the flailing sword of truth decapitates them. Now—all nonsense aside—you know I have no enemies. Only discarded lovers—and they have their memories.

—Maila Nurmi

Vampira. Courtesy of the Jove de Renzy Collection,

When she transformed into a butterfly, the caterpillars spoke not of her beauty, but of her weirdness. They wanted her to change back to what she’d always been.

But she had wings.

—Dean Jackson

Foreword

Dear Aunt Maila:

You grew wings. By the time you reached your 18th birthday, you’d begun to display them in splendiferous Technicolor, much to the consternation and confusion of your family. Collectively, they clung fast to their caterpillar consciousnesses, shook their heads, and made excuses. Your youthful impulsivity was only a phase, they said, which would pass with maturity, and then you’d commit to the traditional life they longed for you and expected of you. That of marriage and motherhood. But what does a caterpillar know of a butterfly?

Your innate desire for creative expression and the freedom to cultivate a lifestyle far different than their own was never taken seriously, and so you did the only thing you could to survive. You flew away.

Did you know you became a lifetime obsession of mine? From the first time I saw you in 1953, at age six, pre-Vampira, all beautiful blonde hair, red lips, and eyelashes, wearing transparent heels that looked every bit like glass slippers, you became my own private Cinderella.

During Vampira’s early years, you appeared on television on The Red Skelton Show. I looked in vain for you throughout the show. It was only afterward I was told that the black shrouded woman, whom I thought was a witch, was you. Although it was only June, I assumed the show was called Red “Skeleton” as an early homage to Halloween.

It was another two years before I saw you again, and this time, Cinderella was in love. Crazy, silly, mindless love. Short hair, no makeup, baggy sweater, capri pants, and barefoot—you uttered barely a word to us and instead perched on your lover’s lap and whispered in each other’s ear, giggling like schoolgirls. At nine years old, I was entranced and secretly wondered if someday this kind of behavior was in my future.

In 1957, Grandma died, and I saw you for the third time. No longer the Cinderella or the giddy girl in love, with your grief etched in your sad, tear-stained face. Considering the wretched occasion of your mama’s death, understandably, I think I loved you even more then.

To me, Vampira is Aunt Maila wearing a black dress and wig. To everyone else, she is the first, the original glamour ghoul—the epitome of goth beauty. Vampira was intended to share just a small part of your life. Instead, once the human cartoon burst forth into the world, she clung to you, her creator, like a second skin for the rest of your life. I know you never expected that, 75 years after the momentous birth of Vampira, she would still draw fans from around the world.

You were the architect of the goth phenomenon. From the moment Vampira first slithered onto the television screen, she captivated America. She was emaciated, with a waist so tiny it defied reality, but was somehow at once voluptuous and beautiful. A ghostly complexion, nails honed to dagger-like claws, and boomerang eyebrows, her visage and silhouette were simultaneously disturbing and curiously pleasant. Once she was observed, one couldn’t look away.

Vampira was the first goth, and in that sense, you were a pioneer. With the character, you defined goth beauty and inspired and beguiled generations—and you continue to do so to this day.

During those decades, before computers, I searched for you. I wrote letters to magazines and newspapers, seeking information on Maila Nurmi a.k.a. Vampira, without a single response. I spent hours on the phone calling Information, using every name I knew you to employ. In 1977, you still couldn’t be located, even as I enlisted the help of the Red Cross, in order to tell you that your brother, Bobbie, was dead.

At long last, in 1989, I found you through an article in the Star magazine. It had been 32 years. As adults, we spent a glorious week together in Hollywood. We laughed, cried, ate, put on the dog for brunch at the Beverly Hills Hotel, got drunk, and because you didn’t own a bed or a bedroom, we slept on the floor with your puppy, Bogie. It was heaven. It was the culmination of my lifelong dream. We corresponded through letters for several years, and at Christmas, I sent you a box of assorted tins of fish and a bottle of wine. I never heard from you again after that. I was devastated. Had I upset you somehow?

On Monday, January 14, 2008, I read the news in the local newspaper. You were gone. My own private Cinderella caught the dream and flew away.

I was your only family, and even with my limited funds, I had to find a way to get to Los Angeles—and fast. Who else besides family are entrusted with final arrangements? I filled out the death certificate and paid for a future cremation. Through what can only be described as a miracle, I found your apartment. Several authorities had to be appeased before I was allowed to enter, because the county deemed you “a celebrity.”

Like your mama before you, you died alone. Alone on the only piece of real furniture you owned, a sofa, with your feet propped on a plastic patio chair. My heart was broken.

You lived by yourself, so I can understand why your living room and bedroom were cluttered with castoffs, old clothes, memorabilia, and debris. But you still kept your kitchen and bathroom spotless.

The only thing I wanted were your writings. Even then, I knew you always wanted to tell your story to the world, and I knew that I would get them published, because I loved you and I owed it to you. It took 12 years.

I found those writings scattered about on the floor, in drawers, in pockets of your clothes, in satchels and handbags, in an envelope behind a picture frame. There were letters you’d written but never mailed. Sometimes there were pages of writings, and sometimes just a sentence or two. A memory here, a memory there. Written on hundreds of scraps of notebook paper, the margins of newspapers, a calendar, a diary, old hotel stationery. On the backs of photocopies of Vampira. This book is the result of cobbling those pieces together. Everything in italics is your own words, verbatim. I thought the public would want to hear directly from you.

They buried you at Hollywood Forever with your baby, Houdini—your dog whom you loved greatly. Your good friend, Dana Gould, told me it was what you would have wanted, and he graciously paid for it—thank you, Dana. I paid for your modest headstone. Someday, I hope to replace it with something more fitting for the Hollywood icon you were—and still are today.

Fly high, Aunt Maila. Beyond these earthly bonds. And fly proud for what you accomplished.

Love,

Sandra

Chapter One

At eight o’clock, on the evening of October 4, 1941, the Greyhound shuddered to a stop at the Los Angeles bus station.

The young woman checked her freshly bleached hairdo, the result of youthful impulse and a long layover in Portland. Her hair was a mess, and her clothes were wrinkled from two nights sleeping in a bus seat, next to a stranger. None of that mattered as she leaped off the bus into the embrace of the warm night air.

“Hollywood, here I come.”

It had been a long battle for her to get to Los Angeles. But finally, two months shy of her 19th birthday, she was there.

Her life began on December 11, 1922, in Gloucester, Massachusetts, joining a brother, Bobbie, only 17 months older. Her father, Onni, christened her Maila Elizabeth after the Finnish author Maila Talvio. The name “Elizabeth” was a nod to his mother. When she was four, Maila’s f

That Easter, in 1927, Maila made her public speaking debut at the Finnish Lutheran Church. For the occasion, Sophie, her American mother, made her a white dress decorated with ribbons and rosettes. There in the front pew, her mama and papa proudly sat with Bobbie between them, sticking his tongue out at her. A nod from Papa signaled that she should begin.

I recited the Bible verse Papa taught me. When I finished, I picked up the hem of my dress & put it in my mouth, exposing my bloomers to the congregation. And then I was in Papa’s arms & he was whispering how proud he was of me as we settled back into the pew. At a young age, I knew I was the favorite of the King.

In Fitchburg, Onni became involved with the political, social, and economic issues in Finland and the effects they had on his fellow immigrants. Although Finland’s Civil War was over, Stalin’s rise to power was concerning, and as a journalist, Onni felt obligated to ferret out the facts.

In 1926, Onni dropped a bombshell on his unsuspecting wife. He was going to Finland. Maybe for a year. He claimed it was his journalistic duty to witness the political upheaval in his homeland.

It was an outrageously selfish act. Sophie was still grieving over the loss of both parents less than a year before, and now she was expected to take on the responsibility of caring for their two young children alone, far away from her familial home. Onni offered to take Sophie along, but he knew she would never agree to leave her children. As an added insult, Onni used Sophie’s inheritance from the sale of her parents’ mercantile store to fund his trip.

The kicker is that, even though she was born in Massachusetts, Sophie was no longer an American citizen at this time. When she married Onni in 1918, the law of the land stated that the bride must take on the citizenship of her husband. So without ever setting foot in Finland, Sophie was now an American-born Finnish citizen living in the United States—without her Finnish husband, who was the whole reason she’d lost her American citizenship in the first place.

After a year, Onni returned to the U.S. The nation was in the throes of Prohibition at the time, and Onni was teetotal, preaching the evils of alcohol at temperance halls. His fellow Finns at the halls greeted him like a rock star upon his return, hungry for the news from abroad. His wife’s welcome was far less enthusiastic.

Maila and brother Bobbie (my dad), in front of their house at 3 Norseman Avenue, Gloucester, Massachusetts

Sophie on the right, her children Maila and Bobbie right in front of her, with family friends. Gloucester, Massachusetts, 1925.

It was almost as if Onni had returned to a stranger. When he came home, he found that Sophie had bobbed her hair and started wearing makeup and shorter skirts. But most alarming was that her agreeable nature had been replaced with something quite unfamiliar: defiance.

As the stalwart Finn preached the gospel of alcohol abstinence to ever increasing audiences, his wife was unapologetically enjoying bootlegged wine. Onni learned that during his absence, his wife had made new friends, and she’d been going out drinking with them, not bothering to hide her new habits. Onni was greatly dismayed by the change, but he assumed it would pass once they resumed their routine.

As an additional insult to Sophie, while her husband was away, he’d changed his surname, Niemi, back to Syrjäniemi, the original Finnish form he’d used before he emigrated to the U.S. Thereafter, a silent though salient wedge divided the family, as Sophie and her children remained Niemis.

The year following Onni’s return, 1928, was an election year. The next president would be either the pro-Prohibition Protestant candidate, Herbert Hoover, or the “wet” Catholic, Al Smith. As Onni’s reputation as a gifted orator gained widespread recognition, he expanded his repertoire to politics. There was never a doubt which candidate Onni preferred. He hated Catholics almost as much as he hated booze. His zeal for Hoover’s candidacy was rewarded when he was selected as one of the Republican’s election speakers to encourage the Finnish vote.

In April of 1929, the family moved to Cleveland, Ohio, where Onni took on the position of editor-in-chief of the Finnish-language newspaper Kansan Lehti. Six months later, Wall Street crashed. As America entered the Dirty Thirties, the economy began its free fall. To ward off financial ruin, the newspaper moved to Ashtabula, 50 miles east of Cleveland, and once more, the Niemis were on the move and the children, aged eight and nine, were uprooted from their school and social life.

The kids gleefully discovered their new neighborhood was full of playmates. There was a diseased black walnut tree on the property, and Maila decided it was the perfect place to play Movie Star, as did her newfound pals.

Playing Movie Star was a favorite game of the girls in the neighborhood. Maila had recently been introduced to movie magazines, which carried stories and pictures of her favorite stars, like Greta Garbo, Louise Brooks, Norma Shearer, and Toby Wing. Women who had everything life could offer, who bathed in jewels, swathed themselves in fur, and rode around in fancy cars—no matter that most of the country was suffering during the Great Depression. Such was the life Maila dreamed of for herself.

Every day, the girls decided who they’d be & I always wanted to be Toby Wing. But the other girls insisted I be Joan Bennett instead. Well, I was not going to concede to their wishes without compensation. So, I said I would IF I got the highest spot in the old tree. It was perfect. Every day I, as Joan Bennett, received the benefit of free rent in the old tree’s penthouse. And everywhere else, there was a depression going on. Oh, it was divine.

A cat, Passenger, and a dog, Timmie, were added to the Niemi family, along with an apparent fugitive from someone’s henhouse. An animal lover, Maila named the chicken Muna, the Finnish word for egg.

The Niemis lived in an upstairs apartment across the street from a grocery store. From her bedroom window, Maila and Bobbie watched the Mr. Goodbars melting in the sun. If the chocolate turned white, those bars could be bought on Sundays for three cents instead of five. Sunday also was allowance day and each kid got 25 cents. Maila and Bobbie would pool their money, grab ten white discounted candy bars and a pound of jelly beans, and with the nickel remaining, they’d buy a Sunday paper.

Bobbie read through the comics and was done, but for Maila, the comics opened a portal into a land of fantasy, allowing her to run wild through the streets of her imagination. When everyone was finished reading, Maila gathered up the comics and stacked them in a pile in her room so she could read them over again.

The Barsettis lived downstairs, and soon after moving in, Sophie and Addie Barsetti became friends. Addie’s kitchen was the hub of her family life, and most days, the pungent, garlicky aroma of a simmering pot of marinara sauce competed with the clamor of kids and dogs running in and out of the house. Muna visited as frequently as an open door would allow, pecking at the crumbs between the floorboards, which Addie called “’crack food.” The Barsettis, an Italian-American family of Catholics, enjoyed wine with every meal, Prohibition be damned. They made gallons of elderberry wine and insisted on sharing it with friends and neighbors.

To Sophie, her friend’s kitchen was everything she’d hoped her married life to be: kids, dogs, laughter, the aroma of dinner cooking, and a husband who would be home every night to enjoy it all.

But it wasn’t meant to be for Sophie.

When Onni was home, his children competed for his attention. Maila, imitating her orator father, took to reciting stories of her own creation. These she read aloud to Onni, as Bobbie interrupted with thunderous sound effects.

As an editor, Onni began his workday among the people, gathering information for his next op-ed. Keeping his finger on the pulse of public opinion was essential, though effortless, for the gregarious Finn. After work, the temperance hall beckoned, and it became his temple, its message his passion. He stood at the podium and raged against the “Devil’s water,” opposing even the use of sacramental wine, and blamed alcohol for everything from infidelity to insanity.

When Prohibition was repealed in 1933, one could buy either a bowl of soup or a drink for a dime. Each offered temporary relief; the decision was whether to appease the beast of hunger or the need for escape. For Sophie, the decision was an easy one. She needed the drink. How else could she cope?