The Chilling, page 1

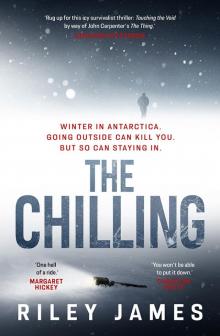

‘Rug up for this icy survivalist thriller: Touching the Void by way of John Carpenter’s The Thing.’

Benjamin Stevenson, author of Everyone on This Train is a Suspect

‘Riley James is one to watch: stoke the fire and lock the windows, you’re in for one hell of a ride.’

Margaret Hickey, author of Cutters End

‘Drier than a Jane Harper novel, more snow than a shelf of Scandi noir, The Chilling is a white-knuckle thrill ride from the first page. One of the best crime debuts of the year. I couldn’t stop reading.’

Aoife Clifford, author of It Takes a Town

‘The Chilling is an atmospheric thriller with a wild setting and a fast-paced plot—you won’t be able to put it down.’

Christian White, author of Wild Place

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

First published in 2024

Copyright © Riley James 2024

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

Cammeraygal Country

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: info@allenandunwin.com

Web:www.allenandunwin.com

Allen & Unwin acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the Country on which we live and work. We pay our respects to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Elders, past and present.

ISBN 978 1 76147 087 5

eISBN 978 1 76118 960 9

Typeset by Midland Typesetters, Australia

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

A Serpent when he is benummed with cold, hath poyson within him, though he do not exert it; ’Tis the same in us, whom only weakness keeps innocent, and a kind of Winter in our Fortunes.

—Justus Lipsius

PROLOGUE

It was a bird that lived on carrion—a bird that ate the dead.

Arindam heard the skua gull before he’d fully regained consciousness. He was still strapped into his plane seat and had no idea how long he’d been there. The impact of the landing must have knocked him out. As he came to, the bird’s repetitive burr echoed over the empty white valley.

There was usually no life in this godforsaken place, nothing that could eat or breathe or even make a background noise—no trees, no dogs, no trilling insects. But now there was this one bird somewhere outside his window. It had to be a skua, didn’t it? The predatory creature was known for scavenging the carcasses of seals and penguins. It also chased, robbed and pirated the food of other birds, and it gorged on their fledgling young. But mostly, it ate the dead.

Oh great, thought Arindam in despair.

He knew his injuries were not catastrophic: there was only a cruel throbbing in his head and a stiffness in his neck—he’d been in worse pain with a dislocated shoulder last summer. But he couldn’t ignore the sickening dizziness and the furious pounding of his heart. He was suffering from severe shock and he wasn’t dressed for minus eight degrees Celsius. A search-and-rescue team wouldn’t make it in time. As an ice driller, he’d done too many field-training exercises to fool himself otherwise: he would soon be carrion.

Prior to the crash, their twin-engine aircraft had been lost, technically speaking. On any other day, the captain would have handled the weather with ease. An experienced pilot and a fellow Brit, Noah was used to flying in snow-covered terrain. He’d flown the same interior route to East Antarctica dozens of times—he’d already transported Arindam’s field research group twice that season—and he knew what to do in a whiteout. But today, when the aircraft had reverted to flying by instruments, something hadn’t been right. Noah suspected the altimeter was broken.

‘We’re not where we’re supposed to be,’ he said, an edge of concern to his voice. ‘I don’t think we’re in position. I’m just going to duck under this cloud bank.’

He was speaking to his co-pilot Roger, but Arindam heard everything from the first row. He’d learnt they’d been in the air too long and should’ve been approaching the runway by now.

‘If I could find the horizon,’ muttered Noah, ‘I’d have a visual reference.’

In an Antarctic whiteout there was no way of telling the difference between the sky and the ground. There was no contrast between the clouds, the great sheet of ice on the water and the snow coating the surface—everything was a uniform shade of white. Usually, the pilot could catch a glimpse of shadow or a jagged peak. But in the current conditions, he was having trouble finding even the landing aids.

‘I don’t like this,’ said Noah, glancing back at his three passengers. ‘This just doesn’t look right.’

His voice had been calm, but when Arindam saw the captain’s face, his stomach plunged. There’d been a flicker in Noah’s eyes, a flash of panic.

Arindam couldn’t remember much after that. There was the deafening roar of the engines as Noah tried to turn the plane, and there was Roger’s frantic mayday call to base. Arindam clung to his seat, the aircraft rocking, his muscles aching with the strain. When he glanced at the window, a blur of white sped past before a grey ridge loomed into view.

Now the plane was still and quiet. There was a pile of snow where the cockpit had been. On top, a pale arm stuck out at an odd angle, stiff and frozen. Arindam registered that it was wearing Noah’s watch before a wave of nausea pulled him under.

When he woke again, a cold wind was blowing through the fuselage. His head felt worse than before. He slowly turned and saw that the tail section was gone. A gaping hole exposed the wreckage to the drift outside. It was still daylight, but the sky had turned a dishwater grey.

‘Hello?’ he croaked into the void. His throat felt dry, like he’d been shouting.

No one replied. No one else was on board. It occurred to him he was going to die alone. Unless there was someone in the tail section? Someone still strapped to their seat? Outside?

As he went to unbuckle himself, pain shot through his hand, a burning pins-and-needles sensation. He groaned and looked down to see a fine crystalline layer of ice had formed on the exposed flesh of his forearm. It extended from his elbow to his wrist, covering the friendship band his daughter Aisha had made for him. With a shock, he realised his skin looked like frozen meat. His body was being devoured by the cold. Soon the blood in his veins would be frozen too. He imagined tendrils of ice stretching up his neck and into his scalp.

The skua sounded its alarm again outside the window. Arindam hunched forward to get a better look. The powerful brown-grey bird was perched on a plane seat a few feet away from the fuselage. It kept bobbing up and down, its pointed wings drawn back like a Viking helmet. It was yanking at something with its frightful beak.

The bird filled Arindam with fear. He moaned into the silence, his heart still pounding. This is no way to die, he thought, with that creature out there waiting for him. He recalled eight-year-old Aisha presenting her gift bracelet, begging him to remember her. For his daughter’s sake, he could get up and stomp his feet; he could get his blood pumping and generate some warmth. Perhaps the feeling would come back to his fingers and he could write a note. Then he could find one of his colleagues—Pete or Barry—and they could shelter together and make a plan.

With fumbling hands, he unclicked the seatbelt. He slid out of the chair onto his knees. His seat was broken and bent, almost ripped from the flooring. His yellow coat rustled as he inched into the aisle and crawled towards the back of the aircraft, panting and moaning. Unable to feel his hands and feet, his limbs got caught in the scattered bags and equipment on the way. When he got to the opening, he tumbled towards the ground below. With a soft crunch and a puff of snow like smoke, he landed on his back. Somewhere in his sluggish brain, he could feel his Polartec trousers grow cold and wet.

Breathing heavily, he struggled to his knees, and looked over the crash site. There was a dirty streak like a drivew

Then he spotted the skua, still on the back of the seat.

He lurched towards the bird, ploughing through the snow on his knees. ‘Shoo!’ he called out hoarsely, as he stumbled forward. ‘Shoo!’

His voice sounded weak to his own ears, but it startled the bird, which hopped to the ground, beating its wings impatiently.

As Arindam rose behind the seat, he spotted an arm thrown over the side. ‘Hello?’ he called, peering around the front.

His heart stalled in his chest.

The broken, twisted corpse was slumped into the cushions. Its head was bent at a sickening angle, with its neck elongated and one cheek resting on its shoulder. The face was livid white, and instead of eyeballs there were only two bloodied holes.

Before he could look away, he noticed that the sockets were framed by torn pieces of flesh and bare patches of skull where the skua had been feasting. On one side of the corpse’s mouth, a row of stained teeth was exposed; on the other, a piece of frozen drool trailed down a white beard.

He had found Pete.

On the flight, the lead scientist had been sitting behind Arindam. A long-limbed man, he kept pushing the back of the chair, until Arindam turned around and glared at him. ‘Sorry, buddy,’ said Pete, who was simply uncrossing his legs. He sounded sincere and Arindam felt bad for being so prickly. It had been a long day: they’d been cutting trenches in the ice since early morning. As a courtesy, Pete moved to one of the empty rows in the tail.

Arindam collapsed against the side of Pete’s chair, his breath coming in great heaving sobs. When the bird returned to its feast, Arindam jerked his head away and staggered backwards. He’d taken only a few steps when his boot plunged through the dusty surface of a snow bridge. He dropped into the crevasse as if through a trap door.

With a hard jolt, he landed upright on a platform hardly wider than a window ledge. The crevasse walls glowed pale blue, and the caverns below appeared eerily lit from within. The sudden fall in temperature was shocking. His lungs gasped for air, and he could no longer feel any part of his body. He was beyond cold, beyond breath and beyond pain.

Barely conscious, he heard a low rumbling in the distance. To his surprise, he realised it was a motor engine: a Hägglunds.

The vehicle stopped, and a door creaked open. There was a flurry of human movement and the crunch of feet on snow. It seemed to go on for some time.

Then a man began talking only a few yards away, his soft Australian twang rising and falling in the wind. ‘There’s no survivors,’ he said. ‘They’re all dead.’

1

‘He’s an arsehole,’ said Daphne.

Kit Bitterfeld glanced up warily from her Sunday newspaper. She’d never heard her mother swear before. Even now, despite the dementia, the word didn’t sound like it should be in Daphne’s vocabulary.

Reluctantly, Kit peered at her mother’s face and took in her confused watery-eyed expression. The elderly woman was seated upright against the pillows on a narrow single bed. Her electric blanket was on even though it was a hot summer’s day, and her cheeks were flushed pink. Her ancient eyes darted about the room.

‘I beg your pardon?’ said Kit, her voice tired and neutral.

‘That man,’ said Daphne, her gaze coming to rest on Kit’s face, ‘your husband.’

‘My ex-husband,’ corrected Kit.

‘Yes, that man. He’s a castle.’

‘A castle?’ said Kit, a little surprised.

Daphne nodded, and Kit nodded back with encouragement. She was relieved to find that it was just a nonsense word, a random firing from her mother’s brain. Kit hadn’t the energy to cope with another outburst, not today.

‘I told you,’ continued Daphne, ‘when you introduced me to him. I warned you about him. I said, “He’s a remarkably handsome man”, didn’t I? We were in the kitchen at the old house, and you said, “We’re going to get married.” And that’s when I warned you. I said, “There’s such a thing as being too good-looking, Kitty.” And that man is too good-looking.’

Kit frowned and shifted uncomfortably. She was disturbed that Daphne had remembered.

That day, the two of them had been alone in the kitchen. Elliot had just gone to the bathroom, and they were waiting for him to come back. They’d been discussing Kit’s new hairdo, a self-styled pixie cut. Her mother was complimenting her, even though Kit had cut the fringe too short and severe. Daphne said she liked it, that Kit looked like a pretty Joan of Arc. Kit was pleased.

That was why the veiled insult took her by surprise.

‘You should be careful, Kitty,’ Daphne said suddenly. ‘A handsome man is like a castle.’

The boiling jug gurgled on the bench, and the teacups rattled ominously. Kit felt a weight in her stomach. Here it comes, she thought. Trust her mother to cut her to the quick with a he-can-do-better-than-you, just when Kit felt so stupid about her hair—and when she already knew Elliot was out of her league.

‘You know the old saying,’ said Daphne. ‘A handsome man is like a castle, and a castle much assaulted will eventually yield. Women will look at him on the street, they’ll make suggestions, they’ll throw themselves at him.’ Her eyes narrowed. ‘And being a man, he’ll like it. He’ll like the attention and the suggestions, just you wait and see—he’ll give in to them.’

In that instant, an image of Elliot from the night before came to Kit’s mind. He was standing at the picnic table in the backyard, talking to boring Lucia from the bushwalking club. He was smiling politely, throwing in a line here and there, helping the conversation along, his square jaw moving and his eyes working their charm. Lucia looked animated for once.

But from where Kit sat inside, she could see Elliot subtly incline his head to the right, to where Melody stood not more than a few metres away.

Melody was wearing a short one-piece jumpsuit, the kind you had to take off completely to go to the bathroom. It made her look even more childlike than her petite frame suggested, despite her tattoos. She was tottering on a steep pair of heels. Earlier in the night, when Kit had made some biting comment about them, Melody drunkenly declared that she could go out dancing in her shoes all night backwards, if she had to. To prove her point, she’d come up to Kit and gyrated her hips. Next to Melody, Kit had felt tall and awkward; she’d moved away and gone into the house.

It was through the living-room window that Kit noticed Melody walk casually up to Elliot and touch his arm. He greeted her as if he’d known she was there all along, had been waiting for her to come over. His smile finally looked genuine.

And so, Daphne had ended up being right: Elliot had been assaulted, and he had yielded. But it had taken some time for Kit to discover the deception. Ten years, in fact. The problem, she now realised, was that his love was a refrigerator light—whenever she saw him, the light was on. His love was a glowing, bright yellow beam. And like an infant she’d assumed the light was on whenever she wasn’t there.

‘Yes, Mum,’ she said. ‘There is such a thing as being too good-looking.’ She gave her newspaper a satisfying flick. ‘Thankfully, I will never have to worry about it.’

‘Yes, I know, I know,’ said Daphne carelessly, and Kit chuckled. But her mother’s next question came like a blow to the chest. ‘Has that woman had her baby yet?’

Kit took a ragged breath and stared intently at the newsprint. The words blurred, but she kept her voice neutral. ‘No, she hasn’t, Mum. Melody’s not due till August.’

Kit’s thoughts flashed back to the week before, the first anniversary of their separation, when Elliot’s best friend Grey had come to her office at the university. She worked there as a researcher in the dental school. ‘Come in,’ she’d said, her mind reeling. She hadn’t seen or spoken to Grey for at least six months, and his visit was unexpected. ‘What brings you here?’

‘Sorry to drop by without calling.’ He failed to look her in the eye. ‘Do you have a moment to chat?’ Without waiting for a response, he came in and sat on the stool by her desk. As he looked down at her, she could see his nasal hairs and a fine sheen of sweat above his lip. He placed his hands on his knees and drew a breath. ‘I wanted—’