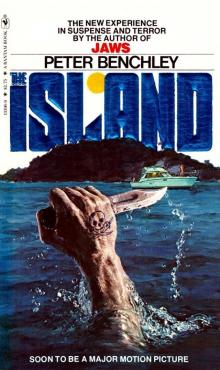

The Island, page 1

Millions of JAWS fans are waiting

to discover Benchley’s newest terror . . .

THE ISLAND

Peter Benchley has thrilled millions of enthusiastic readers with the magic of his bestselling novels . . . Now comes the latest from the man who made you think twice before going anywhere near the water. Now terror stalks the land in The Island . . .

In the Caribbean, a few steps may lead from the sunlit villas of tanned lovers to something evil rotting in the tropical underbrush, from a world of natural perfumes and silken breezes to choking heat thick with the smell of death . . .

In the Caribbean, 610 seagoing boats and 2,000 innocent people have simply vanished . . . apparently lost forever. How could it happen? Why does no one know, or care to know?

Blair Maynard becomes obsessed with finding out what’s going on—and pursues the story to a remote archipelago southeast of the Bahamas. There, on the deceptively inviting waters of the tropics, Maynard and his son sail into as sinister a drama as has ever been played out on the sea . . .

#1 SUPERTHRILLER

THE ISLAND

Bantam Books by Peter Benchley

THE DEEP

THE ISLAND

JAWS

From the Producers of

“Jaws”

Universal Pictures and

Zanuck/Brown Productions

Present

The Most Terrifying

Motion Picture Of the 80’s

“THE ISLAND”

Michael Caine as Blair Maynard

David Warner as Jean-David Nau

Angela Punch McGregor as Beth

Jeffrey Frank as Justin

Plus the most unusual cast of

characters brought to the screen!

A Michael Ritchie Film

Produced by

Richard D. Zanuck and David Brown

Directed by Michael Ritchie

Screenplay by Peter Benchley

THE ISLAND

A Bantam Book / published by arrangement with

Doubleday and Company, Inc.

PRINTING HISTORY

Doubleday edition published May 1979

Bantam edition / March 1980

All rights reserved.

Copyright © 1979 by Peter Benchley.

ISBN 0-553-13396-9

Bantam Books are published by Bantam Books, Inc. Its trademark, consisting of the words “Bantam Books” and the portrayal of a bantam, is registered in the United States Patent Office and in other countries. Marca Registrada. Bantam Books, Inc. 666 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10019.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

for Tracy and Clay

“Romantic adventure is violence in retrospect.”

—adage

“[In a state of nature] No arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

—Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan

T H E

I S L A N D

C H A P T E R

1

The boat lay at anchor, as still as if it had been welded to the surface of the sea. Normally, this far out, there would be long, rolling ground swells—offspring of far-distant storms—that would cause the boat to rise and fall, the horizon constantly to change. But, for more than a week, a high-pressure system had squatted over the Atlantic from Haiti to Bermuda. The sky was empty even of fair-weather clouds, and the reflection of the midday sun made the water look as solid as polished steel.

To the east, a splinter of gray hung, shimmering, suspended a millimeter above the edge of the world: the refracted image of a small island just beyond the horizon. To the west, nothing but waves of heat rising, dancing.

Two men stood in the stern, fishing with monofilament hand lines. They wore ragged shorts, filthy white T-shirts, and wide-brimmed straw hats. Now and then, one or the other would dip a bucket off the stern and pour water on the deck, to cool the Fiberglass beneath their bare feet. Between them, over the socket where the fighting chair would fit, was a makeshift table of upturned liquor cartons, covered with fish heads, guts, and skeins of thawing pilchards.

Each man held his fishing hand out over the stern, to prevent the line from chafing on the brass rub-rail, and felt with the tip of a callused index finger for the tick that would signal a bite, a hundred fathoms below.

“Feel him?”

“No, He’s down there, though . . . if the hinds’ll let him get near it.”

“Tide’s runnin’ like a bitch.”

“It is. Keeps takin’ my bait up the hill.”

Cooking smells drifted aft, mingling with the stench of sun-ripening fish.

“What’s that Portuguee bastard gonna poison us with today?”

“Hog snout, from the stink of it.”

In the darkness of the canyon beneath the boat, a fish of some size took one of the baits and ran with it to a crevice in the rocks.

The man was slammed against the gunwale. Bracing himself with his knees to keep from being pulled overboard, he reached out with his left hand and hauled a yard of line, then a yard with his right, another with his left. “Damn! I knew he was there!”

“Prob’ly a shark.”

“Shark, my ass! That’s Moby goddamn shark if it is.”

The fish ran again, and the man gritted his teeth against the pain in his hand, refusing to let the line burn through his fingers.

The line went slack.

“Bitch!”

The other man laughed. “Man, you can’t fish. You pulled the hook right out his mouth.”

“Bit it off, is what.”

“Bit it off . . .”

He retrieved the line slowly, careful to let it tumble in a pile at his feet, untangled. Hook, weights, and leader were gone, the monofilament severed. “I told you; bit it off.”

“Well, I told you it was a goddamn shark.”

The man tied a new hook and leader to his line. He peeled two half-frozen pilchards from the ball of bait fish, ate one, and threaded the hook through the other—in and out the eyes, along the spine, in and out by the tail. He cast the hook overboard and let the line run through his fingertips again.

“Hey, Dickie.”

“Hey.”

“What time tomorrow, the cap’n say?”

“Noontime. He’s meetin’ the plane at eleven-somethin’. Dependin’ how much crap they got, they should be at the dock around noontime.”

“What kind of doctors they are again?”

“Nelson . . . I told you a hundred times. They’s neurosurgeons.”

Nelson laughed. “If that don’t beat all . . .”

“I still don’t see the funny in neurosurgeons.”

“Head doctors, man. What’s head doctors doin’ goin’ fishin’?”

“Neurosurgeon ain’t just a head doctor.”

“You say. All I know is, after that fella in Barbuda hit me up ’side the head with the ball peen, they sent me to a neurosurgeon.”

“You told me.”

“I baffled him, though, so he sent me to a Czechoslovak.”

“Anyway, no law says a neurosurgeon can’t fish, too. Important thing is, cap’n say they pay cash up front.” Dickie paused. “You ’member how many there is?”

“I never did know.”

Dickie shouted, “Manuel!”

“Aye, Mist’Dickie!” A boy appeared in the door to the cabin. He was slight and wiry, twelve or thirteen years old. His skin had been tanned umber. Sweat matted his hair to his forehead and streaked the front of his starched white shirt.

“How many . . .” Dickie stopped. “You dumb, scramble-headed Portugee sum’bitch! I told you not to wear your uniforms when there ain’t no guests aboard!”

“But I ain’t—”

“Look at your pants boy! Looks like you crapped yourself!”

The boy glanced down at his trousers. The heat in the cabin had steamed out the creases, and the legs were spattered with grease. “But I ain’t got no other pants!”

“Well, I don’t care you have to stay up wash-in’ all night, they better be white as an angel’s ass by first light.”

Nelson smiled. “What do we know, Dickie? Maybe neurosurgeons like dirty little Portugees.”

“Well now, Nelson, maybe you got a point. What d’you say, Manuel? Sh’we let them nooros fool with you?”

The boy’s eyes widened. “No, sir, Mist’Dickie. Whatever that is, I don’t want none.”

“How many bunks you make up?”

“Eight. That’s what the cap’n said.”

Nelson sniffed the air. “What the hell you cookin’, boy?”

“Hog snout, Mist’Nelson.”

Dickie said, “I told you, Nelson. That’s all you’re good for.”

When Manuel had washed and stowed the plates and pots and pans, and had scrubbed the galley clean, he had nothing to do. He would have liked to shut the outside door, turn on the air conditioning and the television in the main salon, and lounge on the velour-covered sofa. But the air conditioning was never turned on except for the comfort of paying guests; there were no signals for the television set to receive; and the sofa—like all the rest of the furniture—was covered by protective plastic shrouds.

There was a bookcase full of paperbacks, and Manuel could have gone to his bunk and read, but his reading fluency was limited to the block letters on packages of frozen food, labels on marine instruments, and place names on nautical charts. He was determined t

Dickie and Nelson were still fishing off the stern. Manuel could have rigged himself a line and joined them, and he would have if they were catching anything. But the banter between Dickie and Nelson increased in inverse proportion to the number of fish being caught, and on days this slow it was ceaseless. If Manuel joined them, they would turn on him as a fresh target, and that he hated.

So he washed his clothes and ironed them, and was bored again.

Dressed only in a pair of mesh undershorts, Manuel walked to the stern. The sun was swelling as it touched the western horizon, and the moon had already risen, a weak sliver of lemon against the gray-blue sky.

“Mist’Dickie, you want I should take the covers off the chairs and stuff?”

Dickie did not answer. He was sensing his fingertips, trying to decipher the faint jolts and tugs on his line, to distinguish between the nibble of a small fish and the first tentative rush of a larger one. He yanked at the line to set the hook, failed, and relaxed.

“No. Leave it be. Time enough in the morning. But if you’re sittin’ around with your thumb in your butt, you might’s well fill the booze locker.”

“Aye.”

“And bring us a charge of rum when you’re done.”

“Can I turn on the radio?”

“Sure. A touch of gospel do you good. Flush the evil thoughts from your mind.”

Manuel returned to the salon. In a cabinet beneath the television set was a bank of radios: single side band, forty-channel citizens band, VHF, and standard AM-FM. At this time of day, most of the receive-and-transmit bands were cluttered with conversations between Cuban fishermen discussing the day’s catch, cruise-ship passengers calling the States (via Miami Marine), and commercial purse seiners telling their wives when to expect them home. Manuel switched on the AM receiver and heard the familiar, anodyne voice of the Saviour’s Spokesman—an Indiana preacher who taped religious programs in South Bend and sent them by mail to the evangelical radio station in Cape Haitien. Most boats cruising in the neighborhood of latitudes 20° and 22° north, longitudes 70° and 73° west, kept their AM receivers locked on WJCS (Jesus Christ Saviour), for it was the only station that was received without interference and that broadcast regular local weather conditions. U. S. Weather Bureau reports from Miami were reliable enough for Florida and the Bahamas, but they were notoriously, dangerously, bad for the treacherous basin between Haiti and Acklins Island.

“. . . and now, shipmates,” crooed the Saviour’s Spokesman, “I invite you to join us here in the Haven of Rest. You know, shipmates, for every soul a-sail on the sea of life there is always a small-craft warning flying high. But if you’ll let him, Christ will stand beside you at the helm . . .”

Manuel rolled back the carpet in the salon, lifted a hatch cover, and dropped into the hold. He took a flashlight from brackets on the bulkhead and shone it on countless cases of canned food, soft drinks, and insect repellent, net bags of onions and potatoes, paper-wrapped smoked hams, tins of Canadian bacon and turkey roll. Crouching in the shallow hold, he moved forward, searching for a case or two of liquor. At most, he figured, three cases: eight people—including four women, who don’t drink as much as the men—for a seven-day trip. Thirty-six bottles would be more than enough. And he knew that guests did not order more than they planned to drink. Food was included in the charter price, but liquor was extra, and leftovers remained on board. Those were the rules.

He moved farther forward and shone his light into the bow compartment. It was full of liquor boxes. He read the stenciled letters on the sides of the cartons, and then, conditioned to distrust his reading, read them again: scotch, gin, tequila, Jack Daniel’s, rum, Armagnac. In his head, Manuel counted bottles, people, and days. A hundred and forty-four bottles, eight people, seven days. Two and a half bottles per person per day.

Manuel knelt on the deck and stared at the cartons and felt ill. This was going to be a bad trip. There would be complaints about everything: When the guests drank too much, nothing was right for them—not the weather, not the comforts aboard the boat, not the food, not the kinds of fish caught nor the number, and especially not each other. Dickie and Nelson and the captain were immune to churlishness; their ages and experience and toughness deterred all but the most reckless of boors. That meant, of course, that the drunks saved their most vitriolic abuse for the young and defenseless Manuel.

He set the flashlight on the deck and tore open the nearest case of scotch. The topside bar could hold two bottles of everything—enough for the first night, at least.

At twilight, the fish began to feed.

“I never could figure it,” Nelson said, hauling in his line hand over hand. “There’s no light down there anyhow, so how’s them buggers know when’s dinnertime?”

“They got a natural clock inside ’em. I read that.” Dickie leaned over the stern. “Well, looka that goggle-eyed bastard.”

Nelson reached for the leader and hauled the fish over the gunwale. It was a glass-eyed snapper, rich, reddish pink, six or eight pounds. As the fish had been dragged from the bottom, the air inside had expanded, bloating the fish’s belly and popping its eyes. The tongue had swollen to fill the gaping mouth.

“Supper,” Nelson said.

“Damn right. Manuel!”

There was no reply. The boy was in the hold, far up in the bow. From the salon came the voice of the Saviour’s Spokesman, backed by a choir: “. . . you may say to yourself, shipmate, ‘Why, Jesus can’t love me, for I am too grievous a sinner.’ But that’s why he loves you, shipmate . . .”

“Manuel!” Dickie started forward. “Goddammit, boy . . .” Looking beyond the salon, through the forward windows, Dickie saw something drifting toward the boat, carried by the swift tide. “Hey, Nelson,” Dickie pointed. “What you make of that?”

Nelson leaned over the side. In the half-light, he could barely see what Dickie was pointing at. It was twenty or thirty yards in front of the boat—dark, solid, twelve or fifteen feet long. Obviously, it was unguided, for it swung in a slow clockwise circle. “Looks like a log.”

“Some robust log. Damn! It’s gonna smack our bows dead-on.”

“Not movin’ fast enough to do no harm.”

“Scrape the crap outta the paint, though.”

The object struck the boat just aft of the bow shear, stopped momentarily, and then, caught in the tide, moved lazily toward the stern.

Below, Manuel heard a dull thump on the port side. He opened a case of Jack Daniel’s, tucked two bottles under his arm, and, holding the flashlight in his other hand, went aft toward the hatch. He reached up and set the Jack Daniel’s on the salon deck. He crouched again and moved forward, ignoring the Saviour’s Spokesman’s exhortation to “. . . write to us here at the Haven of Rest, and we promise to write you back if you will enclose a self-addressed stamped envelope.”

“It’s a boat!” said Dickie.

“Go on . . .”

“Like a canoe. Look at it.”

“I never seen a boat like that.”

“Get a gaff. The big one.”

Nelson reached under the gunwale and brought out a four-inch gaff hook with a six-foot steel handle.

The object was closing fast. “Snag it,” said Dickie. “Wait . . . not yet . . . not yet . . . Now!”

Nelson reached out with the gaff and jerked it toward him. The hook buried in the wood, and set.

It was a huge, hollowed log, tapered at both ends. The tide pulled at it, swinging the far end away from the boat. “It’s a heavy bastard,” Nelson said. “I can’t hold it much longer.”

“Bring her ’round here.” Dickie unlatched and opened the door in the transom used for bringing big fish aboard. He stepped down onto a narrow platform at water level, just over the exhaust pipes.

Nelson guided the log around the stern, into the lee of the boat, out of the tidal flow. The log rocked gently, like a cradle.

Nelson said, “There’s something in it.”

“I see it. Canvas, looks like.”