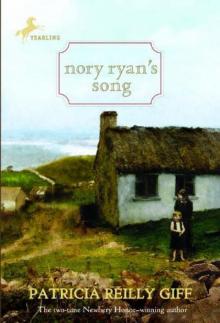

Nory Ryan's Song, page 1

ALSO BY PATRICIA REILLY GIFF

For middle-grade readers:

Lily’s Crossing

The Gift of the Pirate Queen

The Casey, Tracy & Company books

For younger readers:

The Kids of the Polk Street School books

The Friends and Amigos books

The Polka Dot Private Eye books

Published by

Delacorte Press

an imprint of Random House Children’s Books

a division of Random House, Inc.

1540 Broadway

New York, New York 10036

Copyright © 2000 by Patricia Reilly Giff

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher, except where permitted by law.

The trademark Delacorte Press® is registered in the

U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and in other countries.

Visit us on the Web! www.randomhouse.com/kids

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools,

visit us at www.randomhouse.com/teachers

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

For Anna Donnelly,

who stayed.

For the Reillys,

who sailed on the Emma Pearl.

For the Monahans,

who came to 416 Smith Street.

For the Haileys, the Cahills, and the Tiernans,

who finally had that bit of land.

For all of them, my family.

For my children and grandchildren:

Jim, Laura, Jimmy, and Christine

Bill, Cathie, Billy, Cait, and Conor

Alice, Jim, and Patti …

a memory of An Gorta Mór, the Great Hunger.

And most of all

for Jim.

CONTENTS

Cover

Other Books by This Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Glossary

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Dear Reader

About the Author

GLOSSARY

a stór uh stoar my dear

bean sídhe ban-shee female fairy beings who wail when someone is about to die

diabhal djow-uhl devil

Dia duit djee-a-ditch God save you (a greeting)

fuafar fu-uh-fur disgusting, hateful

madra mah-druh dog

poitín puh-tjeen an alcoholic drink made from potatoes

Rith leat! rih-leat Run away!

sídhe shee creatures from another world who supposedly cause trouble

CHAPTER

1

Someone was calling.

“Nor-ry. Nor-ry Ry-an.”

I was halfway along the cliff road. With the mist coming up from the sea, everything on the path below had disappeared.

“Wait, Nory.”

I stopped. “Sean Red Mallon?” I called back, hearing his footsteps now.

“I have something for us,” he said as he reached me. He pulled a crumpled bit of purple seaweed out of his pocket to dangle in front of my nose.

“Dulse.” I took a breath. The smell of the sea was in it, salty and sweet. I was so hungry I could almost feel the taste of it on my tongue.

“Shall we eat it here?” he asked, grinning, his red hair a mop on his forehead.

“It’ll be over and gone in no time,” I said, and pointed up. “We’ll go to Patrick’s Well.”

We reached the top of the cliffs with the rain on our heads. “I am Queen Maeve,” I sang, twirling away from the edge. “Queen of old Ireland.”

I loved the sound of my voice in the fog, but then I loved anything that had to do with music: the Ballilee church bells tolling, the rain pattering on the stones, even the carra-crack of the gannets calling as they flew overhead.

I scrambled up to Mary’s Rock. As the wind tore the mist into shreds, I could see the sea, gray as a selkie’s coat, stretching itself from Ireland to Brooklyn, New York, America.

Sean came up in back of me. “We will be there one day in Brooklyn.”

I nodded, but I couldn’t imagine it. Free in Brooklyn. Sean’s sister, Mary Mallon, was there right now. Someone had written a letter for her, and Father Harte had read it to us. Horses clopped down the road, she said, bringing milk in huge cans. And no one was ever hungry. Even the sound of it was wonderful. Brook-lyn.

The rain ran along the ends of my hair and into my neck. I shook my head to make the drops fly and thought of my da on a ship, the rain running down his long dark hair too. Da, who was far away, fishing to pay the rent. He had been gone for weeks, and it would be months before he came home again.

I swallowed, wishing for Da so hard I had to turn my head to hide my face from Sean. I blew a secret kiss across the waves; then we picked our way up the steep little path to Patrick’s Well.

We sat ourselves down on one of the flat stones around the well and leaned over to look into the water. People with money threw in coins for prayers. But the well was endlessly deep, wending its way down through the cliffs toward the sea, and it took ages for coins to sink to the bottom. Granda said that might be why it took so long for those prayers to be answered.

But not many people had coins to drop into the well. Instead there was the tree overhead. People tied their prayers to the branches: a piece of tattered skirt, the edge of a collar.

“I see my mother’s apron string.” Sean pointed up as he tore a bit of dulse in two and handed me half.

I nodded, sucking on a curly edge. I looked up at the tree. A strip of my middle sister Celia’s shift was hanging there. Now, what did that one want? She had no shame. There it was, a piece of her underwear left to wag in the wind until it rotted away. Every creature who walked by would be gaping at it.

I stood up quickly, moving around to the other side of the well to look down at our glen. The potato fields were covered with purple blossoms now, and stone walls zigzagged up and down between.

And then, something else.

“Sean,” I said, “what’s happening down there?”

Absently he tore the last bit of dulse in two. “Men,” he said slowly. “Bailiffs with a battering ram. Someone is being put out of a house.”

Someone. I knew who it was. A quick flash of the little beggar, Cat Neely, her curly hair covering most of her face. And Cat’s mother, who sat in their yard, teeth gone, cheeks sunken, with no money to pay the rent.

“Don’t think about it,” Sean said, his hand on my shoulder, his face sad. “There’s nothing can be done.”

“Coins,” I said. “If only someone …” I broke off. I knew it myself. No one in the glen had an extra penny. Not Sean’s family. Not mine. My older sister Maggie and Sean’s brother Francey were saving every bit they could to get married. But even that would take years.

The dulse on my tongue tasted bitter now. Cunningham, the English lord, owned all our land, all our houses; he could put any of us out if he wanted. And now it would be Cat and her mother.

There was someone with a coin, I knew that.

Anna Donnelly.

Sean and I were afraid of her. He had said that one of the sídhe might live under her table. I shuddered, thinking of those beings from the other world. Tangles of gray hair, bony fingers pointing, crouched in the darkness. Anna had magic in her, too. She could heal up a wen on the finger, or straighten a bone with her weeds, but only when she wanted to.

And she hadn’t saved my mam the day my little brother, Patch, was born.

That Anna Donnelly had a coin.

And I was the only one who knew about it.

I thought of the day I had stopped near her house. The thatch on her roof was old and plants grew green over the top. And there was Anna outside, teetering on a stool, her white hair in wisps around the edge of her cap. She had peered over her shoulder, her face as wrinkled as last year’s potatoes, then held something up before she shoved it deep into the thatch.

I had seen the glint of it, the shine.

The coin.

And in my mind now: I could save Cat Neely and her mother. If only Anna would give me that coin.

Suddenly my mouth was dry.

I turned to Sean. “Thank you for the dulse,” I said, and left him there, mouth open, as I flew down the path away from the cliff.

CHAPTER

2

I hurled myself along the road, thinking about the bailiffs and Devlin, who collected the rents for Lord Cunningham. They’d tear down the roof of the Neely house and pound at the beam until it splintered in over the hearth. Nothing would be left but dust, and chunks of limestone, and bits of thatch settling on the floor.

Cat would be sobbing, her tiny face blotched, and her mot

I crossed our own field, seeing my sister Maggie drawing a picture on the wall of the house. Three-year-old Patch was dancing around her. “Me,” he was saying. “It’s my face.”

They didn’t see me, and I didn’t stop. What would I say to Anna? I wondered. My da will be home soon, long before the rent is due, I’d tell her. We will give you back the coin straightaway. But right now we could save Cat and her mother. Even the thought of knocking on her door dried my mouth and dampened my hands. But if she said yes I could bring the coin to Cat and put it into her little fist. When she opened her hand, her mother would see it.

I picked up my skirt and catercornered across Anna’s field, one hand covering the stitch in my side. I could feel my fingers trembling. I went up the path then before I could change my mind, rapped hard on the door, and stepped back.

Nothing happened. I leaned forward and knocked again. The door stayed shut. Where was Anna? Where had she gone? Was someone’s baby being born in one of the far glens?

From far away I heard the men shouting. I went out to the path to see if she was coming. Please come, Anna Donnelly. Please.

I turned and looked back at the thatch. The coin was right there. It was so close I could climb up and reach for it.

And then the door opened.

My hand flew to my mouth. I stepped back, so frightened I hardly remembered why I was there.

Anna stared at me with faded blue eyes, her head to one side.

I opened my mouth, but I couldn’t speak.

She took a step outside, listening to the men shouting in the distance. “They are putting the Neelys on the road?” Her lips were puckered, with deep lines around her mouth.

“Lend me a coin for them,” I said in a rush. “I will pay you.”

“And how will you do that?”

“My da will be back. He’ll give it to you. I know he will.”

A louder sound in the distance. Was the house going under?

Anna looked up, thinking, frowning. “I will give you the coin,” she said, “but you will pay for it another way.”

“What do you want?” My lips felt strange as I said it.

“Work for me. Help me gather my weeds and dry them.”

I took another step back, suddenly shivering, holding my hands under my shawl, wanting to run, wanting to go to my own house and be safe. Go to Anna’s house? Help Anna? I could hardly breathe. “I will,” I managed to say.

She pointed to the roof with her cane. While she watched I used the stool to climb. I reached into the thatch, feeling the thick straw dig into my skin and under one of my nails. And there was the coin.

I flew up the road, holding it so hard it made ridges in my palm.

A knot of people were gathered in front. Francey Mallon, my sister Maggie’s beau, was sitting on a stone wall, his face dark with anger, staring at Devlin the agent. And the house: only stone walls standing, dust still rising from where the thatched roof had been. Cat and her mother were gone.

I pulled my shawl closer. “Where are they?” I asked a woman who was peering inside. I stood on tiptoes in back of her. The beam of the house had splintered as it fell. It lay in two great pieces on the floor. A rush potato basket lay on its side, empty.

“Can I take the basket, sir?” the woman asked the bailiff.

“Where are they?” I pulled at her sleeve, pulled hard.

She slapped at my hand. “The basket, sir?” she called again.

“The Neelys,” I said, holding on to her sleeve.

“Gone.” She motioned over her shoulder with her thumb. “Debtors’ prison, maybe. They owed rent, owed it for a long time. Someone said they’ll be sent to Australia.”

I looked at her, horrified. “But that’s where criminals go.”

“I don’t know,” she said, her eye still on the basket. She turned away from me, half ducking inside to pick it up.

Gone. Poor Cat. Poor Mrs. Neely.

I loosened my clenched hand and looked down. Anna’s coin could go back into her thatch. I wouldn’t have to go to her house. I wouldn’t have to learn her secrets. Her magic. I wouldn’t have to see the sídhe under her table.

Just under my feet was something of Cat’s, a small piece of yarn she had worn in her hair. I reached down to pick it up. Australia, I thought.

I circled the house, passing the Neelys’ dog, a great black-and-white sheepdog without a name. She lay in front of the tree, tied to the trunk with a piece of rope. When she saw me she lifted herself to her feet, her tail beginning to wag. I could see how thin she was, how easily you could count her ribs. Did she know she had been left there, that Cat and her mother would never come back for her?

I swallowed, watching her sink down again when she realized I hadn’t come to let her loose. Her eyes drooped as she rested her head on her paws. I tried not to think of what would happen to her.

Then suddenly someone shouted. “You!”

I looked back over my shoulder at the bailiff’s angry face. And I was more frightened than I had been of Anna Donnelly.

I began to run and didn’t stop until I reached the cliff road. Then, more slowly, I climbed until I reached the top and sank down to lean my head against the cool rocks of St. Patrick’s Well.

A footstep in back of me. The bailiff?

I jerked and opened my hand. The coin slid into the well and Cat’s bit of yarn after it. For a moment I could see the glint of the coin, and then it was gone, down, down into water so deep no one would ever find it. The yarn floated on top for a little longer before the water covered that, too.

I turned. The Neelys’ dog stood there, the rope still around her neck, the frayed end trailing on the ground. My arms went around her as I sank down to unknot the rope. I rested my head on her matted fur, thinking. The bailiff hadn’t called me. He wanted the woman next to me and the basket.

I had lost the coin. The precious coin.

Gone forever.

And I would have to go to Anna’s.

The dog’s back was warm and her ears soft against my fingers. She whined a little and began to lick my face.

At last I stood up. The dog wagged her tail just the least bit. I sighed. “Come, madra,” I said. “We’ll go home.”

CHAPTER

3

My middle sister, Celia, sat on the wall of the yard, knitting a shawl. I closed my eyes for a moment, thinking of the one I was knitting. It had a hole I could stick my thumb through, and bits of thistle somehow poked through the stitches. A great mess. And Celia had lost no time in telling me so.

She looked up, her eyes widening when she saw the dog. “Where is your head?” She shook her needles furiously.

Fourteen, only two years older than I, and she wanted to be my mother.

“Look at the size of that beast,” she said, twitching her little nose like Mallons’ goat. “He’d eat as much as I do.”

“She. Her name … is Maeve.” I walked around Celia and inside, blinking in the dim light and nodding at Granda.

Muc the pig in her corner pen snorted when she spotted the dog, and Patch dived into the straw of his bed.

“She won’t hurt you, Patcheen.” My voice was aimed at the doorway. “She’ll be after Celia.”

“Really?” Patch said. He raised his head.

“Not really. She’s a grand dog. I’ve named her after Queen Maeve.” I looked down at her. Her muzzle was white, with small black dots where her whiskers grew, almost like the freckles on Maggie’s cheeks.

Where was Maggie?

“Grand?” Celia came in with the knitting spilling to her knees. “How do you think we’ll manage with another mouth to feed?”

“We just won’t feed you, my girl,” I said. Big Maggie would have laughed, but my heart wasn’t in the teasing. All I could think of was Cat, gone forever, and the coin, and Anna.