The Author's Cut, page 1

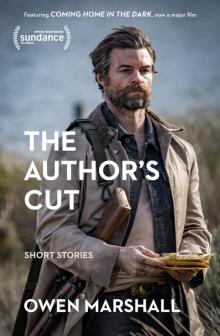

Chosen by the author from his thirteen previous collections, this latest selection of stories includes ‘Coming Home in the Dark’, the inspiration for a new feature film.

Owen Marshall is regarded as one of our finest living writers. His stories capture the imagination and refuse to let go. From dark to funny, acerbic to warm, they probe our national psyche with clear-eyed insight. This selection from a long career ranges across New Zealand and ventures overseas; the pieces explore both cruelty and love; they look back to childhood and also capture the world we live in today. Full of unexpected turns, lyrical writing, wry observations and intriguing plots, this sampling offers a provocative take on New Zealand.

I very much envy his ability to lay things down in such a way that each one has its natural weight and place, without any straining and heaving. — Maurice Gee, Sport

I’m an admirer of Owen Marshall’s literature, with my favourite stories, chapters, etc. — Janet Frame

Owen Marshall has established himself as one of the masters of the short story — Livres Hebdo, Paris

Contents

Foreword by Fiona Kidman

Coming Home in the Dark

Living as a Moon

Mr Van Gogh

The Master of Big Jingles

Iris

Watch of Gryphons

Minding Lear

Blunderer

Mumsie and Zip

The Divided World

Cabernet Sauvignon with My Brother

End of Term

A View of Our Country

The Fat Boy

Freezing

Supper Waltz Wilson

Hodge

Anacapri

The Rule of Jenny Pen

Sojourn in Arles

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Previous Works by Owen Marshall

Follow Penguin Random House

In memory of my brother, Hugh

FOREWORD

With all the beauty of language that words can muster, Owen Marshall has been exploring landscapes in his stories for the past forty or more years with a painterly and poetic eye that defies comparison. But within these gorgeously wrought exteriors, inner lives rage with passion, anger, love and unbridled pain.

The opening story of this collection, ‘Coming Home in the Dark’, must rate as one of the most powerful and terrifying stories in New Zealand literature. Telling, as it does, the story of a family picnicking in a glorious South Island spot, caught up in random and dreadful violence, it portrays the unspeakable, a metaphor for the dark side of our existence that can play out at the high point of our well-being. In a recent interview, Owen Marshall said: ‘Life is precarious, happiness is fragile, triumph and disaster are only a random incident apart.’ In other words, nothing is ever really safe, we should not delude ourselves, we should take nothing for granted. Time and again, in earlier classics like ‘Mumsie and Zip’, ‘The Fat Boy’ and ‘The Rule of Jenny Pen’, we are led into their dangerous territories, and we risk a part of ourselves when we come face to face with them. It takes great courage to write like this, to fearlessly lead the reader into dark, deep, dense places and out again into the light, or, at very least, the hope that light will shine.

But the master storyteller also provides moments of understated humour as well as portraits of love at its most tender: that between couples, between parents and their children, and the power of friendship. The vulnerability of a widowed father caring for his teenage daughter in ‘Freezing’ simply wrenches my heart. These twenty stories, drawn from earlier collections, range around New Zealand and around the world. Marshall writes superb characters, whether they are local school teachers or florists in the South of France, each shining with their own burnished lustre. The last story, ‘Sojourn in Arles’, is among my favourites, capturing the essence of place while revealing a clever and subtle storyline. The writer’s frequent employment of the first person voice gives many of the stories immediacy, yet we are never drawn into the trap of identifying the author as narrator. Each is different, and whether the writer is describing the good or the ugly, these twenty stories are fiercely well informed. There is much to learn about our country and its values, about people’s occupations and their work places, above all, what things and places look like. It is no surprise that the author is distinguishing himself as a poet in more recent writing, or that he collaborates with major artists in his non-fiction work.

These are stories of great beauty, power and emotional intensity. Owen Marshall has been described as a ‘master of the form’, a ‘Chekhov of the south’, labels that he quietly puts aside in conversation, yet they ring true. His incomparable stories enhance our literature and enrich our reading pleasure.

Fiona Kidman

COMING HOME IN THE DARK

Windswept to a bowl of peerless blue, the sky arched above it all; not oppressive on the landscape, but rather an insistent suction that offered to remove everything into the endless, spun abstraction. The lake had a chop on its milk-green opaqueness. The mountains of black and white rose up ahead. There was a fixed intensity in the delineation of shapes and colours; no compromise, no merging.

‘We’ll see Cook again soon, I think,’ said Hoaggie.

‘It’s the boys’ first time up here,’ said Jill.

‘So it is, and it should be a view today that they’ll remember. I hope that all their lives they can think back to this trip — their first sight of Mount Cook.’

‘I wish we were going to ski, though,’ said Mark.

At the head of Lake Pukaki was the flat outwash of the glaciers and the cold, braided streams milky with rock flour. Hoaggie noticed how the sun caught and glittered from surfaces and turns of the water as he drove. For a selfish moment he was without family, and felt a pack on his back, boots on his feet, and heard the skirl of the wind on the rock faces.

Jill was telling the boys what the Hermitage was like, based on somewhat hazy recollection of a visit well before she and Hoaggie had shifted to Auckland. Her sons were more interested in the outside opportunities of the place. ‘Well, make sure you don’t lose anything today. We can’t come back. Check your stuff.’ She didn’t believe in having the twins dressed the same. She said the modern thinking was to encourage a natural growth of separate identity. Both the boys wore linen shorts, but Mark had a jersey and light, suede boots, while Gordon had a ribbed, blue jacket and sneakers. Gordon had more to say, but Mark was more stubborn.

They passed Bush Creek, and Hoaggie recalled for his wife a climb that he and Tony Bede made to the saddle from there. He experienced as he talked a quick reprise of the euphoria of youth, but had no words to articulate it. They passed Fred’s Creek and saw a Mercedes abandoned on its side in a ditch of stones.

‘Look at that. Yeah, wipeout,’ enthused Gordon. He and Mark scrabbled to see more from the back window as they went on.

‘Someone overdid it there,’ said Hoaggie.

‘And can’t have had any help for miles,’ said Jill.

‘You remember when Bruce Trueno broke down on the Desert Road last Christmas and when he came back with the tow-truck he found the wheels stolen.’

The outwash was mainly an expanse of shingle, but those parts not recently swept by the channels had rough pasture and matagouri, briar, clumped lichens. Beef cattle were feeding by the road. There was oddity in the sight, because of the close proximity, although distinct by altitude, of ice and snow and screes. The inside of the car was more comfortable still: the sun warmed it and the breeze was excluded.

‘Moira wants to nominate me as the Regional Arts Council rep on the grants board,’ said Jill.

‘Who better if you’ve got the time. Go for it.’ Hoaggie was always gratified when his wife proved her competence in her own right. Successful himself, he felt no threat from the achievements of others. He realised also, that because of his own focus on work, his wife had given much of her time to the family. ‘They would be lucky to have someone of your ability,’ he said in all sincerity.

‘Flatterer.’ She rested her hand on his arm. ‘You won’t say that if you’re left to cope when I’m away.’

They came up the final slope to the head of the alpine valley beyond the lake’s expanse. Scenery has little intrinsic appeal to the young, but even the twins, accustomed only to the landscape of the North Island, gazed quietly for a few moments at the sheer valley sides and the towering bulk of Cook and Tasman among their barely less impressive fellows. Then Gordon elbowed his brother. ‘Now those suckers are big,’ he said.

‘I had a talk with Athol Wells at Rotary a while back,’ said Hoaggie. ‘Did I tell you that?’

‘Athol Wells?’

‘He’s the deputy principal at Westpark. You must remember; I said that maybe he’d have an angle on a school for the boys.’

‘I don’t want them to go to a boarding school. You know that.’

‘Well, neither do I personally. It’s what’s best for them in the long run though, isn’t it?’

‘What better environment can you have than your own family?’

‘Roddy Sinclair says he’s going to Wanganui Collegiate,’ put in Gordon.

‘Spastic,’ said his brother. Hoaggie had almost forgotten they were in the back. He dropped the subject.

Hoaggie turned off the Hermitage road and on to the track that led them to the area where camping was allowed. He was pleased to see almost as few amenities, as few small climbing tents, as he remembered.

When the family stood

‘Come on, come on,’ shouted Gordon, and as if it were a consequence, almost immediately there was the shivering rumble of an avalanche on Mount Cook, although not on the faces they could see.

‘Let’s hope no one’s under that lot,’ said Hoaggie.

‘No one would be climbing where that’s likely to happen, would they?’ asked Jill.

‘Sometimes I guess it’s just luck.’

The four of them started on the walking track to the Hooker, which wound through the tussock and thorns of the old, heaped moraines. They were out of the breeze from the snowfields for a while and it was pleasantly warm. Jill put her hand on Hoaggie’s collar. She ran her nails up and down the back of his neck as they walked behind the twins. ‘Maybe you’re right,’ she said. ‘About the secondary school thing.’

‘Maybe not,’ said Hoaggie. ‘What the hell. We can work it out among us all. It’s about giving them the right start, isn’t it?’

Mark had found a stick, discarded by a previous walker. He flourished it proudly, and Gordon began questing on both sides of the track as they went on, searching for a stick that would restore his equality. They could hear the sound of the swift stream from the little lake at the glacier’s snout and the track began to wind over heaped greywacke shingle and boulders.

Below them two other people were climbing up to join the track. The man in the lead was thin and pale; he shrugged his shoulders as he walked. The man behind was immensely solid, the features of his full face seeming indented like those of a snowman. He wore a denim jacket so tight that it pulled his arms back, accentuating the bulge of chest and stomach. Neither of them was old, but men nevertheless, not boys. The big man behind was singing a song from Phantom of the Opera, but only the tune was an identification; the words had been replaced by ta and la. The one in front wore a denim top as well, but of a much darker blue against which light stitching stood out. The stoop of his thin shoulders made the sides of the jacket hang below his waist, while the back rode up showing the grubby white of his T-shirt.

Having ta-laed himself to the end of the music of the night as he reached the path ahead of Hoaggie and his family, the big man followed his friend with a gait grown suddenly shambling without a melody. Neither man looked back; neither waved.

Gordon sniggered and was joined by Mark. ‘Don’t be rude,’ said Jill.

‘What a geek,’ said Gordon, doing a quick chesty imitation of the man’s walk. It was true they seemed unlikely nature lovers.

‘It takes all sorts,’ said Jill.

The two men were soon lost in the turns of the track through the moraine and when the family reached the swingbridge there was no sign of them. Hoaggie was happy to share the surroundings with no one but his wife and children: he had deliberately planned on being there before the school holidays began and in that had been very loyally supported by Gordon and Mark. Such feelings of exclusivity were selfish, Hoaggie knew, but part of his response to beauty.

There was the small lake among the shingle and boulders at the glacier’s end. Etched icebergs floated there, freed from the rocks that covered the ice flow. Some of them had seams of dirt, or stones, some had the flat tints of very old milk. Other ice showed in the banks where the overlay of shingle kept it from the sun. Impressive though it was, Hoaggie knew it to be only the remnant of the ice-age days and he pointed out the ledges and striations hundreds of feet up the valley sides where the great rivers of ice had been thousands of years before. ‘Hey, yeah,’ said Gordon. ‘Next time, Mark and I’ll climb up there and roll stuff down.’

They walked for an hour up the Hooker and then sat for a while before beginning a return. In the clarity of the mountain air the soaring ridges and coruscating sweeps of snow were deceptively near at hand, and even the stunted olearia, hebe and cottonwood where they rested seemed to have a special sharpness of form. Just occasionally they were caught by the edge of a passing breeze and drew their shoulders in for warmth.

On the way back, shortly before the carpark, Hoaggie took a snap of his wife and the twins just below a cairn that commemorated the death of mountaineers many years before. As he lined it up through the viewfinder he had a sudden sense of image within image, of time within time: the shot as it would be with all the others in the album, the wider freeze frame, transient, but stronger just for that instant, showing the four of them together there at the foot of the mountains with the grasses and flowers, the spiked matagouri and the sheen of the great snow slopes in the distance. Hoaggie had no god to pray to, but he offered a sort of prayer nevertheless, which was part gratitude for what he had, and part plea for continuance.

‘Take another one and let me hold the stick in it,’ called Gordon.

The brown grasses were ungrazed and high as Hoaggie’s knee. Where the moraine was exposed the grey stones bore badges of lichens — green, yellow, silver and silver-blue. Some puffed out a little from the rock like the frilled head of a lizard; others were so fine, so delicate, they seemed more like fossils within the rock than anything that grew on its surface. The small white and pink flowers glistened on the humped bushes among the stones, and flies, quick and colourful, were in a euphoria of pollination.

As the family went on to their car and the grassy clearing where camping was allowed, the sounds from the Hermitage carried clearly to them, but subdued in that great natural space. No wind at all in the low clearing, and just a toss of cloud at Cook’s summit to show the westerly at work.

The boys wanted to eat at once, but Jill didn’t wish to have their picnic near the tents and within sight of the small toilet block. ‘There’s always red sleeping bags and socks out to air,’ she said. ‘Always someone with an empty, unpleasant laugh.’

So Hoaggie drove back down the valley just a short distance, and took the turn-off to the Blue Lakes and ventured into the tussock grass along its side. There was a bridge not much further on, and on the high side of that a cluster of alpine beech as a feature in the treeless area around them. Hoaggie nosed the Volvo between matagouri bushes so that the boot was ideally placed to service a grassy area behind it. Jill took out the tartan rugs and told the twins to sort out a good place without stones. The long, dry stalks held up the rugs at first, but Gordon and Mark rolled over and over on them to crush them flat.

‘I hope you checked for any stuff under there,’ said Hoaggie.

‘You mean poop,’ said Gordon delightedly.

‘Anything,’ said Hoaggie.

‘But especially crap,’ said Gordon.

‘Crap,’ repeated Mark.

‘That’s enough,’ said Hoaggie.

Hoaggie and Jill ate on the rugs there, propped on their elbows like Romans, and looking down because of the late-afternoon sun. The boys grappled and snorted through their food, pursued grasshoppers, collected chrysalids, scratched themselves, claimed to see skinks beneath the stones they lifted. Eventually they, too, lay on the rugs, talking in their own close language.

Hoaggie relaxed on his back, his hand across his face as a shield from the sun. He could smell chlorine from the swim a day ago, and the sultanas from the muffin he’d held, and also a scent from the hair on his wrists that had something of tobacco although he didn’t smoke.

He was wondering if it was time to consider buying a bach in the Coromandel, and thinking of the joy the twins would have there, when they stopped arguing with each other and in the pause he heard Jill say, ‘Hoaggie.’ Her voice wasn’t loud, but had an odd formality. He took his hand away and squinted up into the sun. Two men were standing close to them, among the briars. The same men that the boys had laughed at on the track.

The big man put on a silly smile when he realised the family were watching, as if he wanted to appear friendly, but had never checked the expression to ensure that it accorded with his intention. He cracked his knuckles and looked at the food on the rugs. The other man was more interested in the twins. He took several long steps to bring himself up to them, and as they sat up he pushed them down again with his foot. Mark still had something of a smile, as though he thought the men might turn out to be part of a joke his father was playing on them, and he didn’t want to be too easily taken in. ‘Oh, my God,’ said Jill. She put her hands to her face. Hoaggie stood up, clumsy after lying in the sun all that time.