World's Best Mother, page 1

-

Dissecting the myth of motherhood

A thirty-five-year-old writer decides she wants to have children. Rounds of IVF treatments and several years later, she has two daughters and sits down to write this book. World’s Best Mother is a sublime journey—through pregnancy, the mothering of small children, marriage, an affair—which unfolds in a heady mix of anecdote, imagination, and social commentary. Clever and insightful, the narrator examines the myth, but also the scam, of motherhood, openly dialoguing with voices of the past that in one way or another have fueled her condition as a woman: from the legendary hominid Lucy—“the mother of humanity”—to Cinderella, passing through Plato, Mother Teresa, Darwin, Maupassant, and Simone de Beauvoir along the way. Humor, love, and horror converge in this lively auto-fictional battle between the intensity of child rearing and the writer trying to fight her way out.

-

Praise for World’s Best Mother

“This sincere and visceral chronicle of motherhood is very revealing.”

El País

“Prepare to read a book like you’ve never read before, one that breaks the bounds of the narrative and the biographical, the conventions of both traditional and alternative values. A book of humor, love, and pain; as intoxicating as strong wine and as tumultuous as life. The truth is that I can’t imagine the possibility of someone not liking it.”

ROSA MONTERO

“A story told from the edge of a knife, a fictionalized chronicle that investigates pain and darkness, but also love, solidarity, and hope.”

TodoLiteratura

“In clean, quick, and pointed prose that gets into the reader’s soul from the start, Labari’s novel leaves space for reflections on pain and makes room for understanding and coming to the aid of the fragile, incidental individual in today’s society.”

El Confidencial

“Nuria sheds a light on this chaos of darkness that I inhabit when I think about my motherhood (or non-motherhood).”

PAULA BONET

“Nuria Labari shows that living motherhood and writing about it is the new punk. A book against social conventions and against the predictable.”

SERGIO DEL MOLINO

“There are many ways to talk about motherhood, but Nuria Labari’s book is profoundly original and brilliant. This novel is an explosion, an intellectual journey through the most primary instincts and the most human love. Nuria Labari has written a necessary book on a universal theme.”

LARA MORENO, author

“Labari infuses this story with some of her own experience, going beyond the life of a protagonist who lifts the veil on stereotypes and turning this text into a universal story about motherhood loaded with humanity, doubts, humor, regrets and imperfections.”

El Diario

“This novel joins the debate already opened by public figures such as Samanta Villar: the ambivalence generated by motherhood in contemporary female identity.”

ANABEL PALOMARES, Jared

“For Labari, the important thing is to take the issue of motherhood to the streets and to books, to take away that sense of duty to be maternal that floods us and infiltrates our way of living sex.”

PAOLA ARAGÓN, Fashion & Arts

“Nuria Labari’s book must be read slowly, with a pencil, underlining. And, at the end of each chapter, get up, walk, think. It is both a necessary and insufficient book: we need more women, we need more mothers, more non-mothers, more workers, more artists, more grandmothers, more cleaners, more executives, more single mothers … We need more voices. That said: how well you think and what a pleasure to read you, Labari. Somebody take care of those girls for a while, please. Let Nuria keep writing.”

PALOMA BRAVO, Zenda

-

NURIA LABARI was born in Santander and is a writer and journalist. She has written for El Mundo, as well as Telecinco, where she was the editor in chief for web content. She is currently a frequent contributor to El País. Her short-story collection Los borrachos de mi vida (“The Drunkards in My Life”) won the seventh Premio Narrativa de Caja de Madrid in 2009. In 2016 she published her first novel, Cosas que brillan cuando están rotas (“Things That Shine When Broken”). World’s Best Mother is her latest work.

KATIE WHITTEMORE translates from the Spanish. She is the translator of Four by Four (Open Letter Books, 2020) by Sara Mesa, and her work has appeared in Two Lines, The Arkansas International, The Common Online, Gulf Coast Magazine Online, The Brooklyn Rail, and InTranslation. Current projects include novels by Spanish authors Sara Mesa, Javier Serena, and Aliocha Coll (for Open Letter Books), and Aroa Moreno Durán (for Tinder Press). She lives in Valencia, Spain.

-

AUTHOR

“We are the first mothers in the world, in some ways, who have had to study the same, or a little more, and work the same hours as before, when we have a baby. In fact we are the first to be the same as men until we have children, and this makes us very different from previous generations of mothers. And not only that: we are the first to worry about freezing our eggs, the first to seek companies willing to freeze them, the first to have children with another woman’s eggs, the first to have children with another woman, the first to share the custody of our children with our ex-partners. I wrote this book because it seemed to be of literary, political, and social urgency: an important way to understand the world we live in. We can’t understand reality without literature, without this way of thinking about our lives.”

TRANSLATOR

“What I loved most about translating this book was simply spending time with the narrative voice: playful, intelligent, irreverent, dipping into humor and pathos by turns. I read this book feverishly, underlining passages, thinking of the women and men I knew would nod along in recognition once they had the chance to read it in English. My happy challenge was to capture Labari’s style in all its light and shadow, and delve with her into the tension between motherhood and other acts of creation.”

PUBLISHER

“I am sure many people—not only women—will enjoy this astute meditation on the joys and curses of motherhood. It’s well written, clever, funny, and profoundly honest. Nuria Labari is unsparing in her description of the way motherhood affects one’s sexuality. I am proud to introduce this new and highly original voice into the body of literature on motherhood and writing.”

-

Nuria Labari

World’s Best Mother

Motherhood, Ambivalence, Writing, Ambition,

Infertility, History, Sexuality, Love, Abortion,

Philosophy, Marriage, Infidelity

Translated from the Spanish

by Katie Whittemore

WORLD EDITIONS

New York, London, Amsterdam

-

Published in the USA in 2021 by World Editions LLC, New York

Published in the UK in 2021 by World Editions Ltd., London

World Editions

New York / London / Amsterdam

Copyright © Nuria Labari, 2019

English translation copyright © Katie Whittemore, 2021

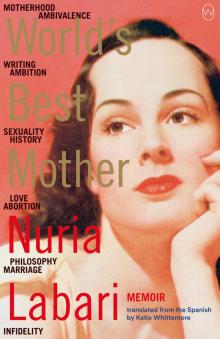

Cover image © The Print Collector/Heritage-Images/Scala, Florence

Author portrait © Adasat

The quote in chapter 2 is from the Bible, New Revised Standard Version, Genesis 3. The quotes in chapter 3 are from The Trial by Franz Kafka, translation by Idris Parry, copyright 1994 by Penguin Random House, pp. 170–172. The quote in chapter 4 is from The Divine Comedy by Dante, The Inferno: Definitive Illustrated Edition, translation by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, copyright 2016 by Dover Publications, canto II, verses 70–73. The quote in chapter 5 is from the Bible, New Revised Standard Version, Genesis 28. The quote in chapter 20 is from “Elegy 1” by Rilke, accessed from https://www.poemhunter.com/poem/elegy-i/.

This book is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental. The opinions expressed therein are those of the characters and should not be confused with those of the author.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data is available

ISBN Trade paperback 978-1-64286-072-6

ISBN E-book 978-1-64286-087-0

First published as La mejor madre del mundo in Spain in 2019 by Literatura Random House, Barcelona.

This edition is published by arrangement with International Editors’ Co. Literary Agency.

Support for the translation of this book was provided by Acción Cultural Española, AC/E.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Twitter: @WorldEdBooks

Facebook: @WorldEditionsInternationalPublishing

Instagram: @WorldEdBooks

www.worldeditions.org

Book Club Discussion Guides are available on our website.

-

For Esther Gómez Echaide, mother

-

ONE The Punctuality of Playmobil Bunnies

I’m a woman, I’m a mother, I can’t have children, I write. I can’t have children, I’m a mother, I write, I’m a woman. I write, I’m a mother, I’m a woman, I can’t have children.

I’m a woman, not a bird. And some evenings, just before I dissolve into the traffic jam that will carry me home, I try to determine the minimum distance I should maintain with respect to other members of my own species. Some days—today, for example—I wonder if such a distance even exists. To be honest, all my points of reference were blown sky high when I became a mother. Everything’s up in the air now. Everything except me. Because, unlike birds, I can’t fly.

“They’re doing the tests tomorrow,” I said to MyMother.

Five years ago. The brief flash of her scared-squirrel face.

“I don’t understand what they can tell you from a blood test. I know you think I’m very old-fashioned, but this is something new, all the stuff you girls go through these days. I never wanted to have children. I mean, not like people want them nowadays. I got pregnant without realizing it. I didn’t plan, I didn’t try. Of course, I was younger than you are—twenty-four. Can you imagine? You wouldn’t have been an only child if your father hadn’t died, that’s for sure. It’s different now. My gynecologist told me that you’re not actually very young at thirty-five, that the reason you’re not getting pregnant is because you waited too long. But it’s your insistence that I don’t understand. Babies come when they come, and if you start planning on them, they don’t. I certainly wouldn’t have had you, if I’d stopped to think about it. No, listen. One day, I showered to go out with your aunts, and when I went to put on my green dress with the buttons, it didn’t fit. I thought it had shrunk. It didn’t even occur to me to think that I’d gained weight. But I was pregnant. And I didn’t stop gaining, more than fifty-five pounds in the end. After I had you, I never weighed less than 130.”

“I’ll get the results in ten days.”

“Me! Who never weighed more than 110 pounds and had to eat cornstarch to put on weight!”

I recall many conversations that I had with MyMother when I was trying to get pregnant, all of them immaterial. Talking to one’s own mother is impossible because mothers are like mute magpies: they never shut up, but they don’t have anything to say. MyMother doesn’t stop, words gush from her. The same messages day after day, year after year. The same stories. Her chatter, a music aimed at the back of my head. Like a revolver. And yet, it’s a kind of comfort, too: when I talk to her, I’m not looking for dialogue or ideas, but the hum, her melody. Sometimes I just want the sound of her voice saying whatever it has to say, and what I have surely heard before. It used to drive me crazy. I wanted her to be direct. I thought her ideas didn’t make sense, that she could do better. But now, I think it’s because she’s MyMother, a mother, and that means she knows her music is all I’ll have left when she dies. She doesn’t want to leave me alone.

The medium is the message and the mothers of the world decided a long time ago that it had all been said before. No one ever listened to them, anyway.

The thing is, four years ago I too became a mother. And what’s worse is I still haven’t found my own melody. That’s why we’re here, in this book that will be my failure and disappearance as a mother and as a writer, when I haven’t established myself in either field.

I’m an amateur mother and I’m already done for. I write behind my daughters’ backs, like they aren’t enough. I write when I should be playing with them or telling them a story or making a cake. And when this book is finished they will know.

But I’m not really what you’d call a writer, either. I’ve written a few dozen short stories—one of them won a local prize—a novel I haven’t managed to get published and another I haven’t managed to finish. I make money as a creative director in a digital marketing agency. I’m good at it, they pay me well, and I enjoy myself. I have no excuse for spending my child-rearing days writing, and much less writing about motherhood, which will be the definitive confirmation of my lack of literary ambition. Because I don’t think you can be an artist and write as a mother.

Talented artists are daughters, always their mothers’ daughters regardless of whether or not they have their own offspring. Good writers write about daughterhood, or about any other subject in which their point of view forms the center of the universe. Like Vivian Gornick’s Fierce Attachments, an autopsy of motherhood in which she is the daughter, of course, because Gornick is a creator. In contrast, a mother is always the satellite of another more important body. A mother is the antithesis of the creative Ego. “Mothers do not write, they are written,” pronounced the psychoanalyst Helene Deutsch around 1880. Arguably, this still stands today.

That’s how I know that if I persist in this, I’ll end up strolling into publishers’ offices with a manuscript under my arm that will sooner or later be labeled “a woman’s intimate journal,” an invisible category that, in book circles, denotes a highly suspect lack of literary ambition.

I read enough to know that any text that smacks of the female experience is to literature what tampons are to the big drugstores: a “feminine hygiene” product. In Europe, you can buy Tampax in the same places you buy expensive perfume, but each product sits on its own shelf and every shelf has its value.

The masculine experience, by contrast, has always invoked universal themes. There are no “typically male subjects” because for centuries boys’ themes belonged to everyone. At least that’s what I notice whenever I’ve poked around in the intimate experience of a man I’m close to. But the reverse doesn’t happen often. The male experience is all of ours, while the female experience belongs to women alone.

This subtle poison of prejudice is perceived throughout literary history. Sometimes I think about how if Kafka’s Letter to His Father had been a Letter to His Mother, it would have been considered the clucking of a hen and not a rooster’s proud crow. We’ve accepted that some are destined to wake the very sun with their morning call while the rest of us limit ourselves to pecking at the ground and laying eggs.

If that weren’t enough, there is a silent—and silencing—battle between what it means to create as a mother and to create as a woman. There are three unwritten rules: a woman’s most important creation will be her children, motherhood her greatest achievement, and, for as long as she lives, her children will be her greatest passion. This is why I think there are so many more mothers who write than there is writing by mothers: we almost always prefer to use what we create to connect with the other I that we are able to be when we aren’t raising children. Out of my way for a moment, child, I’m going to write, I’m going to dance, I’m going to act, I’m going to paint. I read authors (mothers) who talk about writing as “their space.” And they write an article or a few stories about motherhood, or poems, lots of poems, entire books of poems, sometimes. In writing about motherhood, it seems you must betray either yourself or your child, or maybe both, as in my case. There is only one way that the experience of motherhood becomes universal, and that’s the death of a child. At that point, you just have to dig in, because there’s no other way to go on, if one can somehow go on. The creator’s point of view (her pain) is once again the center of the universe.

In The Year of Magical Thinking, Joan Didion approaches the theme of motherhood (among others) after her husband’s death and the serious illness of her daughter, who would die shortly after the book was published and about whom she would write in Blue Nights. Her autofiction is a contemporary classic; it’s not relegated to the tampon shelf. Maybe tragedy is the only way to turn motherhood into a universal theme. Maybe without pain, there are no universal themes. Maybe without pain, there is no universe.

And so, in general, great women writers focus on their writing in addition to their children (when they have them). Two circus rings. Two types of music, two dances. This is the best-case scenario, of course, when the mother-artist divides herself between raising children and creating. The problem is that I’m not even a writer, and I haven’t suffered any misfortune that legitimizes my need to write about motherhood. My responsibility—without a doubt—is to take care of my daughters and keep quiet. Because nothing hurts. Because everything is fine, really. The girls are fine, Man is fine, work is fine. We are healthy enough, have enough money. But here I am, holed up in a café, far from them, writing, when I know this is bad for them, I know that the three of us would be better off if I went home and we hid out in the bottom bunk. If we started to play Playmobil zoo, baby edition, and I made a cave with the comforter to protect us from a pretend storm. And set up the fences for the jungle beasts and the pens for the farm animals. It must be time to feed the Playmobil bunnies right about now. They’re always terribly punctual.