David Ambrose, page 1

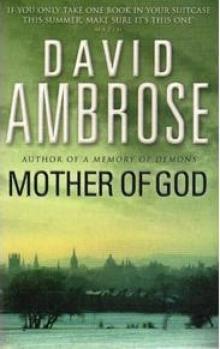

MOTHER OF GOD

Tessa Lambert is young, beautiful and a genius. She has just created the first viable artificial intelligence programme. But her discovery is so controversial that she must keep it a secret even from her colleagues at Oxford University. How could Tessa have been aware that soon there was to be a hacker stalking her on the Internet: a serial killer who has already terrified California, a killer who unbeknownst to anyone is about to give her secret invention its own terrifying and completely malevolent life …

MOTHER OF GOD

BY

DAVID AMBROSE

Complete and Unabridged

CHAPTER 1

SHE thought she might tell him when they took their Easter break together in Brittany. It depended how things went. She wasn’t trying to trap him into anything. She accepted full responsibility: she was twenty-nine years old old enough to run her own life.

All the same, he had a right to know. Whether he was interested or not was up to him. If he was horrified at the idea of a child, then they would go their separate ways without rancour. She had already decided that she wasn’t going to ask for financial support. She would bring up the child herself. Other women women she admired had done it, and so could she.

What worried her was that he might propose some sort of half-measure: for instance, that she have the baby but they keep their relationship on its present easygoing basis, no commitments either way. This, she had decided, wouldn’t work. The child would have a full-time father or none at all.

The streets of Oxford were relatively free of undergraduates when she drove to the lab that morning. Most of them had already left for the Easter vac. She and Philip were due to set out for France on Thursday. She was going to pick him up in London at his friend Tom’s flat in Earl’s Court, where the two of them were putting together the summer issue of the poetry magazine they co-edited.

She had hardly spoken to Philip in the last few weeks; he had been frantic down there, and she had been equally busy up here. She had joined him for one brief weekend, but it had been mostly parties and people and a fringe theatre show, and there had been no time to talk about a baby. It would be easier abroad, walking on the beach, perhaps, with Mont St Michel in the distance. That was how she imagined it.

His handwriting was immediately recognizable on the second letter she pulled out of her mail box. The postmark was London, Saturday. She opened it quickly, not giving herself time to wonder what it was all about. But she had only to read the first couple of lines to know.

My dear Tessa,

This is the hardest letter I’ve ever had to write. Part of me wishes I had the nerve to tell you to your face, but the rest of me thanks God that I don’t, because I couldn’t have borne that look of strange resignation you always get when something, or someone, disappoints you.

He went on to tell her that he’d been seeing this other woman for three months now. The trips to London to work on the magazine had been increasingly a cover. The woman, whose name he didn’t mention, came like him from Australia. Now that his twelve-month visiting lectureship at Oxford was coming to an end, they had decided to go back together. He didn’t give any more details, just finished off with some standard sentiments about how his time with Tessa had been precious, how he would always be grateful and would never forget her. Et cetera. Goodbye.

She realized she was still standing there gazing blankly at the letter some moments, maybe even minutes, after reading it a second time. She began again, but stopped. There was no point, no more to get out of it, no secrets between the lines. It was over.

Footsteps echoed around her on the old, cracked marble floors of the administrative building as people went about their business. Fortunately no one she knew well went past; she didn’t know how she would react if someone spoke to her. She turned and walked out quickly, got into her car, and sat behind the wheel.

Why would he have sent the letter here to the lab instead of to the cottage? Not that it mattered, but there must have been a reason.

She unfolded the letter again and her eyes ran over the familiar phrases. There it was: time. He and the woman were leaving Heathrow this morning. They would be in the air before she got to the lab. That must have been how he wanted it. No thought that she could absorb a shock like this better at home than where she worked. That wouldn’t have occurred to him.

How little he understood her. How little he cared. How little in the end, she told herself, it mattered. She crumpled the letter into a ball inside her fist, then wondered what to do with it. She pushed it deep into the pocket of her long, loose jacket. Then she wondered what to do with herself.

Damn it, she would go in to work. That was always the best therapy. If someone asked her about Easter, which they were sure to do, or mentioned Brittany, because she had told her friends, she would just say that there had been a change of plan. She wouldn’t go into details. It was nobody’s business but hers.

Like the baby. That was now nobody’s business but hers. But she had been prepared for that; she just hadn’t been prepared for the decision to be made so soon.

Well, it was behind her. So was Philip. He never would have made a father anyway. The idea was ridiculous. She and the baby were well shot of him.

She shut her car door firmly, locked it, and started briskly back across the gravel towards the labs. She paused only for an instant. Anyone watching would have thought that she was trying to remember something that she might have left behind.

What she was actually doing was asking herself whether she, Tessa Lambert, one of the brightest minds in this university of very bright minds, was capable of looking after a helpless, infant life.

CHAPTER 2

SPECIAL AGENT Tim Kelly peered down from the helicopter as it started its descent towards the hills behind Malibu. He could see the cluster of vehicles already at the crime scene and the tent which had been erected over the body.

Moments later he was inside the tent with Lieutenant Jack Fischl of the Los Angeles Police Department, and Bernie Meyer, the medical examiner.

“Two kids from Pepperdine found it on their morning run,” Jack Fischl was saying, jerking a thumb in the general direction of the nearby university campus. “Scared off a couple of coyotes who’d started breakfast. Hard to know how much was the coyotes and how much him.”

Tim looked down at the remains of what had been a young woman, and an attractive one if the other victims were anything to go by. Not that they’d looked much better than this one when they’d been found, but subsequent identification and comparison of photographs had shown that he went for a certain type. She was white, in her twenties or early thirties, not heavy but with a full figure. The modesty implied by the pale bikini lines on the stretches of her flesh that had remained untouched was mocked by the grossness of her death. She was his seventh in eighteen months. Predictably enough, the press had already dubbed the killer ‘the LA Ripper’.

Bernie Meyer rolled her on to her side to examine the dark patches of post-mortem lividity on her back. Rigor mortis had set in and Tim noticed that the bruise-like spots where blood had congealed beneath the skin after death did not correspond with the points at which the body had been in contact with the dry, uneven ground beneath it. Like the others, she had been killed elsewhere, then dumped.

“Dead twelve to fifteen hours is my guess,” Bernie said in his matter-of-fact tenor. The light voice came unexpectedly from his stocky frame and bullet-like bald head. “Strangled, then dumped here before rigor set in say between midnight and 3 a.m. Can’t say much more till I get her to the lab.”

Tim knew that there wouldn’t be much more to say even then if the killer was running to form. None of the autopsies had yielded any secretions: semen, blood, or tissue. They had nothing to go on apart from psychological profiles, but no leads and no suspects.

Jack Fischl ducked down to get out of the confined space with its smell of death, and Tim followed him. They both breathed in the sea breeze blowing off the Pacific. All around them the Crime Scene Unit was going over the ground with their usual fine-tooth comb, bagging anything from cigarette ends to buttons, book-matches, and strands of hair, always on the lookout for any soft piece of earth that might have held a tyre-print or a footprint. But there was little chance of that up here.

Jack Fischl lit a cigarette and offered one to the bored photographer sitting on his camera box, waiting to see if he’d be needed again. Then he looked over at Tim with a little shrug of helplessness. Tim liked the slow-moving, middle-aged cop. Relations between the FBI and local police weren’t always easy, but Jack had no chips on his shoulder or old axes to grind.

“You don’t have to stick around if you don’t want to,” he told Tim. “I’ll fax everything over to you soon as we have anything.”

“There’s not much I can do till we have some ID,” Tim said, glancing at his watch. “It’s still early for missing person reports.”

“Anything from the phone traces?”

Tim shook his head. “Slow, slow, slow,” he intoned.

Jack nodded in sympathy. Both knew what they meant: phone taps across state lines, not to mention international frontiers, were impossibly complex to get approved and set up. The problem was that in this case phone taps were their best and perhaps only hope.

The killer’s first two victims had belonged to the same computerized dating service, which had led the police to believe that they had a relatively simple task to break this case. But after every single male who conceivably had access to the infor

Then Fischl himself had the idea of using phone taps to find out if some hacker was getting into the data bank illegally; and sure enough they found one. But their elation was short-lived. The hacker was coming in over the Internet, which is the point at which the FBI became involved.

The Agency had established that the calls were entering the nationwide network from an international one, at which point the trail vanished into a geometrically horrifying multitude of possibilities, each one protected in its turn by a stack of legal safeguards and political obstacles. By the time that the enormity of the problem became clear, there had been four murders, all of them in the Greater Los Angeles area.

Logic dictated that LA was where the killer lived; but tracing him around the world and back to his lair, somewhere in the region’s eighteen million-plus inhabitants, would have daunted Superman, let alone Special Agent Tim Kelly.

As the helicopter climbed back into the sky and turned southeast for the FBI building in Westwood, Tim gazed out with growing depression at the hazily overcast urban carpet beneath him. There was something unnatural about this city. It had grown in a desert along earthquake fault-lines where cities didn’t belong. That it should nurture more than its fair share of maniacs and misfits was somehow to be expected.

But what was he, or any of his kind, the law enforcers of the land, supposed to do about it?

What do you do when there is nothing you can do? Except pray, if you believe in prayer. Tim didn’t. But to his surprise, as he sat there with the roar of the helicopter’s motor in his ears, he found the words of a prayer forming in his brain.

“God help us to find this one. Because if he doesn’t, I don’t know who will.”

CHAPTER 3

HELEN TEMPLE’S rambling house in north Oxford was, as always, a tumble of children and dogs. Tessa wondered at the energy required to manage all this, plus a brilliant but charmingly vague husband, and still run a full-time career as a doctor. When she had asked one time, Helen had only laughed and said, “The trick is not to panic.”

Her friend was, Tessa suspected, a truly happy woman. The thought filled her with awe and fear, a certain amount of envy, a touch of scepticism, but above all with curiosity. That was why, whenever her emotions became confused, Tessa turned to Helen.

“I’d already made up my mind that I was going to have the baby. I’d thought of every possible combination of Philip’s reactions, both sides of all the arguments, the good and the bad compromises … I was ready for everything. Except this.”

“In reality,” Helen said after a while, “you’re only in the position you were quite prepared to put yourself in if he hadn’t been willing to promise that he’d be a proper father to the child: on your own, without him.”

“Logically that’s true. But that’s not how it feels.”

“You feel betrayed. And you have been. He’s behaved like the selfish bastard we both knew he was.”

Tessa was silent. “Maybe I didn’t have the right to give him the choice of being a father or not. I mean, it was just my definition of the role that I was imposing on him …”

“You never even got the chance to try, did you? At least you were going to face him with what was on your mind. What did he do? Screwed around furtively behind your back, and sent you a coward’s letter. If you’re going to get involved with a shit, at least pick one with some courage.”

There was a silence between them in the kitchen which overlooked the leafy garden, a silence broken only by a grunt from one of the dogs as he heaved himself away from the warmth of the Aga and drank noisily from a bowl. The children had dispersed for football, the cubs, and choir practice, so the house was briefly still.

“If there were a cure …” Tessa began.

“… we’d bottle it and make a fortune,” Helen finished for her.

It had been their old joke ever since Tessa had spent some time in analysis. She’d broken off when she said that now she understood her problem, but couldn’t see any chance of a cure this side of getting too old to bother with men anyway. So she went on falling for bastards who betrayed and hurt her, and never for the nice guys who wouldn’t. The trouble was that bastards were more fun. They made her feel sexy and exciting. They took everything for granted, and yet nothing at all. The worst, the silliest thing, was that there always came a point in the relationship where she told herself that she would be the one to change him this time.

She laughed with resigned self-knowledge when she thought about how classically she fitted into all the textbooks. But knowing didn’t change anything. It was supposed to, but it didn’t. Knowledge, she had decided, sometimes had feet of clay.

If there were a cure …

“A cure in this case,” she said after a while, “implies a simple answer. And the price you pay for simple answers is being wrong consistently.”

“You manage to be consistently wrong about the men in your life, and yet I’ve never heard you give a simple answer about anything.”

Tessa smiled. Her friend’s frankness, brutal though it was at times, was the emotional anchor of her life. She wondered if Helen understood just how important she was, and decided that she probably did; it was just that Helen carried all responsibility, including this one, so lightly. It was a gift of some kind. A gift for life. How Tessa would have liked to have it.

But then how could she, when they had such different backgrounds?

“You know something,” she began hesitantly, “this is completely illogical, but for a second when I read the letter, I found myself thinking that I wasn’t going to keep the baby after all. As you said, I’d been prepared to throw Philip out of my life and have it; but when he walked out, I wondered. Can you understand that?”

Helen turned her gaze from the early evening light outside the window and studied her friend’s downcast face for a while before speaking.

“What it suggests,” she said eventually, “is that maybe you’re not as confident about having this child as you want to think you are.”

Tessa looked up and met her gaze. Helen saw pain in the look, but also indecision, and pressed on.

“Look,” she said, leaning forward slightly in the creaky wicker chair, “suppose you had confronted Philip, and he’d said very plainly that he wanted you but didn’t want the baby. You think you would have told him that that wasn’t an option. But you don’t know. You can’t be sure what you’d have done. There’s still that little area of doubt that maybe you aren’t as committed to going through with this as you’ve told yourself you are.”

Tessa leaned back against the cushions of the corner seat and rubbed her fingers down the centre of her forehead. “The only good thing about not keeping the baby,” she said, “would be that I could have a large gin, right now.”

Helen smiled sympathetically. They had been through the arguments together many times. Helen was a Catholic, though with a flexible attitude to dogma. She believed in birth control and abortion in certain circumstances, no matter what the church might say. No Pope or College of Cardinals came between Helen and the God she felt she understood better than any of them.

Tessa, on the other hand, had no beliefs: at least not of a religious kind. She did not believe that there was anything sacred about a human egg, fertilized or otherwise. It was not yet, she told herself, a living being, just a biochemical process in its early stages. As a scientist, Tessa knew that sharp distinctions between life and non-life did not exist; nature was infinitely subtle, shaded, and ambiguous.

“All the same,” she said with quiet firmness, “I want the baby. This baby. I don’t know why, but I know I do.”

“Okay,” Helen nodded and pushed herself up from her chair. “Then we’ll leave the gin where it is, and I’ll make a fresh pot of tea.”

CHAPTER 4

HE sat in darkness except for the glow of his screen. His fingers moved over the computer keyboard with the relaxed precision of a jazz pianist coaxing out an improvisation for his own amusement. His staring eyes rippled strangely as they reflected and at the same time absorbed the dense streams of information that scrolled endlessly before them.