Night Magic, page 1

Published by

ALGONQUIN BOOKS OF CHAPEL HILL

an imprint of Workman Publishing

a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

1290 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10104

The Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill name and logo are registered trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

© 2024 by Leigh Ann Henion. All rights reserved.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture. The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

Portions of “Fireflies Blinking” appeared in different form in the Washington Post. Permission to reprint “To Know the Dark” granted by Wendell Berry.

Design by Steve Godwin.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Henion, Leigh Ann, author.

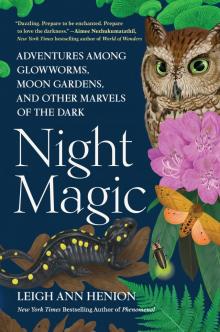

Title: Night magic : adventures among glowworms, moon gardens, and other marvels of the dark / Leigh Ann Henion.

Description: First edition. | Chapel Hill : Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, [2024] | Includes bibliographical references | Summary: “In a glorious celebration of the dark, nature writer Leigh Ann Henion invites us to leave our well-lit homes and step outside to embrace the biodiversity that surrounds us”—Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2024021972 (print) | LCCN 2024021973 (ebook) | ISBN 9781643753362 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781643756196 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Henion, Leigh Ann. | Night gardens. | Night. | Phenogodidae. | Fireflies.

Classification: LCC SB433.6 H46 2024 (print) | LCC SB433.6 (ebook) | DDC 635.9/53—dc23/eng/20240617

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2024021972

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2024021973

ISBN 9781643756196

E3-20240902-JV-NF-ORI

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Preface

SEASON OF INSPIRATION Fireflies Blinking Synchronicity

Rising

SPRING Salamanders Migrating Under a Rock

Where the Sidewalk Ends

Watching a Salamander Dance

Owls Nesting The Astronomer and the Owl

Blue Light Refugees

What Is Darkness, Really?

All the Life We Cannot See

Glowworms Squirming Local Tourist

The Cartography of Evening

SUMMER Moths Transforming Shadowbox

Mothapalooza

Invitation to a Moth Ball

Bats Flying Bat Blitz

Close Encounters

Flight for Life

Foxfire Glowing Vision Quest

Learning to Walk

Tiny Lanterns

FALL Moon Gardens Blooming The Language of Flowers

Heirloom

Secret Gardens

Humans Surviving Burnout

Core Strength

Remembering How to Blink

Acknowledgments

Discover More

Also by Leigh Ann Henion

Selected Bibliography

Additional Resources

For Archer, my adventure partner,

and for everyone

who has ever felt lost in the dark

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

How insupportable would be the days,

if the night with its dews and darkness

did not come to restore the drooping world.

—HENRY DAVID THOREAU

To go in the dark with a light is to know the light.

To know the dark, go dark. Go without sight,

and find that the dark, too, blooms and sings,

and is traveled by dark feet and dark wings.

—WENDELL BERRY

Preface

Years ago, I heard a story about a boy who was lost, alone, in the woods. When a man from the search-and-rescue team found that child, curled like a baby rabbit among leaf litter, he did not lift him from the forest floor. He did not whisk the boy away to an artificially lit, human-built space. Instead, he lowered himself to the ground beside the boy and asked him to describe what he had heard and seen and felt during the long hours he’d spent in the dark, terrified.

At his rescuer’s prompting, the boy described the sounds of creatures cackling, the feel of tiny feet tickling his skin. In return, the man, to the best of his ability, explained what had been going on around him. That first responder understood that, for the rest of the boy’s life, his memory would wander back to that place. And, if he had been properly introduced to the creatures he’d encountered there in the dark, he would not have to continue living in fear of them.

Unfortunately, most of us are rarely advised to hold space for darkness, and it’s difficult to find guides that might help us better relate to it. Against darkness, the Western world has a deep cultural bias. Almost every storyline we’re familiar with suggests that we should banish it as quickly as possible—because darkness is often presented as a void of doom rather than a force of nature that nourishes lives, including our own.

But darkness is an integral and essential part of the human experience, and it’s one that we are collectively losing. Organizations ranging from DarkSky International to the American Medical Association have implored the public to fight light pollution, which has been shown to cause increased rates of diabetes, cancer, and a variety of other ills, as well as degradation to entire ecosystems. Still, light pollution continues to grow.

What might we discover if we pause to consider what darkness offers? What might happen if we, as a species, stopped battling darkness—negatively pummeled in popular culture and even the nuance of language—as something to be conquered and, instead, started working with it, in partnership?

This is the story of how I set out to re-center darkness by spending time with some of the diverse and awe-inspiring life-forms that are nurtured by it. We are surrounded by animals who rise with the moon, gigantic moths and nocturnal blooms that reveal themselves incrementally as light fades. In the past, I might have conceptualized a journey to align with natural darkness as requiring a jaunt to the Canary Islands, the darkest place on Earth. I might have neglected the nocturnal expanse of my Southern Appalachian homeland. But we are increasingly in need of models of how to find wonder on our own patch of planet. In this way, I hope my quest will strike curiosity that can be applied by anyone, to any nocturnal landscape.

Darkness turns familiar landscapes strange, evoking awe by its very nature, in ways that meet people wherever they stand. In Appalachia, as everywhere, night offers a chance to explore a parallel universe that we can readily access, to varying degrees. Nocturnal beauty can be found not only by stargazing into the distant cosmos or diving into the depths of oceans, but by exploring everyday realms of the planet we inhabit.

We, along with everyone we know, have relationships to darkness that influence how we think about it, talk about it, and move through it. But, unlike that child found in the woods, we’re rarely given opportunities to contemplate our experiences. Whether we are swimming in bioluminescent tides off the coast of California or watching iridescent moths hover over a sidewalk in Brooklyn, nearly anywhere on Earth can—at the flip of a switch—become a wilderness of possibility.

As you travel with me through the fern-sprouting valleys and cloud-cresting peaks of Appalachia, encountering creatures both familiar and strange, I hope you will join me in recognizing darkness as a restorative balm for this burning world. And by the time you’ve turned the last page, I hope you won’t feel the impulse to always quicken your step when encountering darkness, imagining perils. Instead, when you come across shadows, I hope you’ll be inspired to sometimes slow your stride, alert to marvels.

Season of Inspiration

Fireflies Blinking

Synchronicity

I’ve been in Great Smoky Mountains National Park for less than an hour when I’m mistaken for a woodland fairy. Even though I’m here to witness the ethereal phenomenon of synchronous fireflies—a species famed for its ability to flash in unison—the association is surprising since I’m feeling more like a haggard dweller of the modern world than an enchanted being of old-world mythology. In fact, when I hear a stranger calling out from across the forest glen I’m wandering, it takes me a second to realize that she’s addressing me. She waves me over and asks again: “Are you a magical creature?”

The woman gestures toward the two young children with her and says, “We saw you walk down to the river, and then you disappeared. I told the girls you must be magical. This whole place is magical. Reminds me of Narnia or something.”

It does feel like we’ve traveled through a portal to another realm. The woman is sitting on a porch stoop, but there’s no porch. And there’s a chimney nearby, but no house. To reach the Elkmont-area trailhead, we—along with hundreds of other visitors here to witness the synchronous fireflies’ light show, which generally occurs in a two-week period

In 2021, Tufts University released the first-ever comprehensive study of firefly tourism. They found that, globally, one million people travel to witness firefly-related phenomena every year. Given that the synchronous fireflies of Elkmont are some of the most famous fireflies in the world—and that I live in Southern Appalachia, their home region—coming across the study during a pandemic lockdown made me think it was past time for me to see these brilliant creatures.

The firefly event in Great Smoky Mountains National Park, which straddles this section of Tennessee and North Carolina, draws visitors from across the continent. Years ago, the National Park Service instituted a lottery for people to secure passes since the species’ growing popularity raised concerns about conservation. I explain to the woman that I’d dipped down to the river for a brief respite from the crowd. She empathizes. Even with attendance limitations, the annual gathering isn’t a small one.

I’m here hoping to glimpse fireflies’ bioluminescence, or living light, partly because I’ve been spending too much time basking in the illumination of screens. I’ve fallen under the influence of phones, computers, and tablets. For several seasons now, I’ve been beating myself against screens like a moth against a lightbulb, seeking entertainment that might numb me, news that might serve to comfort me. In a time of global confusion, I’ve been trying to find answers that do not exist. The process has only served to disrupt my animal instincts—and the influence of artificial light in my life isn’t limited to electronics.

According to DarkSky International, 99 percent of people in the United States live under the influence of skyglow—diffuse, artificial brightening of the night sky—with a loss of unfettered access to the blinking sun-and-moon patterns with which we evolved. Internationally, light pollution is increasing at exponential rates with no signs of slowing. It’s as if we, as a species, have grown afraid of the dark. Tonight, I’m hoping to break the spell that artificial lights have cast.

Along the trail designated for firefly viewing, people have been setting up folding chairs as if they’re waiting for a parade. They’re a diverse bunch. Despite the awkwardness of talking to strangers in the dark, I learn that there are nine-month-olds and ninety-year-olds among them. Some of them have been to the firefly viewing several times. Some, from the West Coast, are awaiting the first firefly sighting of their lives. They’ve come alone. They’ve come with their families. They’ve come because this event is something they’ve always wanted to attend and, due to the state of the world, they’ve stopped taking next year for granted.

Firefly habitat is so specific, so mercurial, that it’s possible to see a great show from one section of the trail while another remains relatively dark. No one, not even rangers, can predict the best seats for the evening, so people mill around until they find a spot that feels right to them. Finally, dusk comes.

When the first synchronous fireflies appear, sporadically flashing, they don’t seem, to my untrained eye, to be much different from common species that illuminate backyards across the country. But as their numbers grow, expectant murmurs travel up and down the row of spectators. Instinctually, when hundreds of insects grow to be thousands—each appearing to light the next in line, like a candle being passed—the crowd stands.

For a while, the insects’ rhythms remain a bit discordant, like those of an orchestra warming up. Scientists have found that the more individuals participate, the more in tune the insects become. Before long, it’s clear that the fireflies are working in unison. The effect isn’t a lights-on-lights-off situation, as I’d expected; it’s more like watching one of those raised-hand stadium waves, when people at a sporting event sequentially lift their hands, swept into the fervor of something larger than themselves.

The insects are responding to each other’s light, working with their neighbors to find their role in the whole. From a distance, the activity appears as a shimmering current of light running through the forest from right to left: Whoosh. Then darkness. Then again, a whoosh of light.

I cannot see the face of the woman beside me, but I come to attention when she calls out, “Dun, dun, dun, dunnn,” mimicking Beethoven’s famous symphony motif. “It’s like they’re playing music,” she says to someone beside her.

Spontaneously, I pipe up: “I couldn’t help overhearing what you just said about music. Have you heard about how the synchronous fireflies were found here?”

“Whoa, a messenger from the dark!” she says, laughing. “No, tell us!”

So I share what I’ve heard, about how naturalist Lynn Faust, who used to spend summers in the now-defunct Elkmont community, grew up admiring the fireflies we’re watching. As an adult, she came across an article about synchronous-flashing fireflies in Asia, and she recognized similarities in what the scientists were reporting and what she’d seen as a child.

When she reached out to researchers in the 1990s, they were skeptical that an unknown-to-science species existed in the most-visited national park in the country, so she sent a musical composition mimicking the sequence of flashes in Elkmont. It’s what convinced firefly scientists that they should make the trip to Great Smoky Mountains National Park, where they confirmed a never-before-recorded synchronous species: Photinus carolinus. This is, ultimately, how we all ended up here, bearing witness this evening.

I can sense more people gathering around me as I’m speaking. When I finish, strangers’ voices ping to my left, to my right, from the trail behind me. Their words ring like bells.

“Amazing!” says a baritone.

“Fantastic!” shouts a soprano.

“What, exactly, do you think they’re singing?” a man asks the crowd.

“Beyoncé! ‘All the Single Ladies’!” a woman says. Laughter ripples up and down the trail.

Most people in attendance seem to be familiar with the concept of firefly flashes as a function of courtship. The insects we’re seeing are males, signaling to females who stay close to the ground. Scientists generally agree about the utility of fireflies’ bioluminescence as mating-related, but they’ve long tussled over how, exactly, fireflies make light. It’s generally thought that illumination occurs when fireflies send nerve signals to their lanterns—allowing oxygen to ignite inborn organic compounds in their bodies. This means, in a roundabout way, that when you see fireflies light up, you’re watching them inhale. And these fireflies are pulsating like cells of a glowing, forest-size lung.

Collectively, the crowd gasps and sighs as fireflies crackle. But despite the dazzle, I find my eyes drifting downward toward the infinitely dark ground. Because once I started researching fireflies, I came across this unshakable fact: By the time we see fireflies in flight, they have potentially been living among us for up to two years in various life stages, dimly glowing on the ground. What we’re witnessing now is the grand finale of a long-term metamorphosis. These famed fireflies have spent much of the past year crawling around in the dark to find what they needed to survive so that their species might ultimately thrive.

There are more than 2,500 known species of fireflies in the world, and 19 of those—with synchronous being the most famous—reside within the borders of Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Will Kuhn, Director of Science and Research at Discover Life in America, a nonprofit centered on biodiversity, believes there are even more. “I don’t think we’ve found all firefly species in the park,” he says. “And there’s still a lot we don’t know about the ones we have found.” If that’s true, there is a chance we won’t know what we’ve got even after it’s gone. Globally, firefly populations are under assault, and the largest threats to their well-being—according to the Tufts report—are habitat loss, pesticide use, and light pollution.