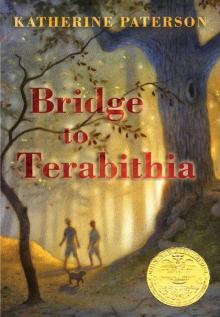

Bridge to Terabithia, page 1

Katherine Paterson

Bridge to Terabithia

Illustrated by Donna Diamond

Dedication

I wrote this book

for my son

David Lord Paterson,

but after he read it

he asked me to put Lisa’s name

on this page as well,

and so I do.

For David Paterson and Lisa Hill,

banzai

Contents

Dedication

One

Jesse Oliver Aarons, Jr.

Two

Leslie Burke

Three

The Fastest Kid in the Fifth Grade

Four

Rulers of Terabithia

Five

The Giant Killers

Six

The Coming of Prince Terrien

Seven

The Golden Room

Eight

Easter

Nine

The Evil Spell

Ten

The Perfect Day

Eleven

No!

Twelve

Stranded

Thirteen

Building the Bridge

About the Author

Other Books by Katherine Paterson

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

ONE

Jesse Oliver Aarons, Jr.

Ba-room, ba-room, ba-room, baripity, baripity, baripity, baripity—Good. His dad had the pickup going. He could get up now. Jess slid out of bed and into his overalls. He didn’t worry about a shirt because once he began running he would be hot as popping grease even if the morning air was chill, or shoes because the bottoms of his feet were by now as tough as his worn-out sneakers.

“Where you going, Jess?” May Belle lifted herself up sleepily from the double bed where she and Joyce Ann slept.

“Sh.” He warned. The walls were thin. Momma would be mad as flies in a fruit jar if they woke her up this time of day.

He patted May Belle’s hair and yanked the twisted sheet up to her small chin. “Just over the cow field,” he whispered. May Belle smiled and snuggled down under the sheet.

“Gonna run?”

“Maybe.”

Of course he was going to run. He had gotten up early every day all summer to run. He figured if he worked at it—and Lord, had he worked—he could be the fastest runner in the fifth grade when school opened up. He had to be the fastest—not one of the fastest or next to the fastest, but the fastest. The very best.

He tiptoed out of the house. The place was so rattly that it screeched whenever you put your foot down, but Jess had found that if you tiptoed, it gave only a low moan, and he could usually get outdoors without waking Momma or Ellie or Brenda or Joyce Ann. May Belle was another matter. She was going on seven, and she worshiped him, which was OK sometimes. When you were the only boy smashed between four sisters, and the older two had despised you ever since you stopped letting them dress you up and wheel you around in their rusty old doll carriage, and the littlest one cried if you looked at her cross-eyed, it was nice to have somebody who worshiped you. Even if it got unhandy sometimes.

He began to trot across the yard. His breath was coming out in little puffs—cold for August. But it was early yet. By noontime when his mom would have him out working, it would be hot enough.

Miss Bessie stared at him sleepily as he climbed across the scrap heap, over the fence, and into the cow field. “Moo—oo,” she said, looking for all the world like another May Belle with her big, brown droopy eyes.

“Hey, Miss Bessie,” Jess said soothingly. “Just go on back to sleep.”

Miss Bessie strolled over to a greenish patch—most of the field was brown and dry—and yanked up a mouthful.

“That’a girl. Just eat your breakfast. Don’t pay me no mind.”

He always started at the northwest corner of the field, crouched over like the runners he had seen on Wide World of Sports.

“Bang,” he said, and took off flying around the cow field. Miss Bessie strolled toward the center, still following him with her droopy eyes, chewing slowly. She didn’t look very smart, even for a cow, but she was plenty bright enough to get out of Jess’s way.

His straw-colored hair flapped hard against his forehead, and his arms and legs flew out every which way. He had never learned to run properly, but he was long-legged for a ten-year-old, and no one had more grit than he.

Lark Creek Elementary was short on everything, especially athletic equipment, so all the balls went to the upper grades at recess time after lunch. Even if a fifth grader started out the period with a ball, it was sure to be in the hands of a sixth or seventh grader before the hour was half over. The older boys always took the dry center of the upper field for their ball games, while the girls claimed the small top section for hopscotch and jump rope and hanging around talking. So the lower-grade boys had started this running thing. They would all line up on the far side of the lower field, where it was either muddy or deep crusty ruts. Earle Watson who was no good at running, but had a big mouth, would yell “Bang!” and they’d race to a line they’d toed across at the other end.

One time last year Jesse had won. Not just the first heat but the whole shebang. Only once. But it had put into his mouth a taste for winning. Ever since he’d been in first grade he’d been that “crazy little kid that draws all the time.” But one day—April the twenty-second, a drizzly Monday, it had been—he ran ahead of them all, the red mud slooching up through the holes in the bottom of his sneakers.

For the rest of that day, and until after lunch on the next, he had been “the fastest kid in the third, fourth, and fifth grades,” and he only a fourth grader. On Tuesday, Wayne Pettis had won again as usual. But this year Wayne Pettis would be in the sixth grade. He’d play football until Christmas and baseball until June with the rest of the big guys. Anybody had a chance to be the fastest runner, and by Miss Bessie, this year it was going to be Jesse Oliver Aarons, Jr.

Jess pumped his arms harder and bent his head for the distant fence. He could hear the third-grade boys screaming him on. They would follow him around like a country-music star. And May Belle would pop her buttons. Her brother was the fastest, the best. That ought to give the rest of the first grade something to chew their cuds on.

Even his dad would be proud. Jess rounded the corner. He couldn’t keep going quite so fast, but he continued running for a while—it would build him up. May Belle would tell Daddy, so it wouldn’t look as though he, Jess, was a bragger. Maybe Dad would be so proud he’d forget all about how tired he was from the long drive back and forth to Washington and the digging and hauling all day. He would get right down on the floor and wrestle, the way they used to. Old Dad would be surprised at how strong he’d gotten in the last couple of years.

His body was begging him to quit, but Jess pushed it on. He had to let that puny chest of his know who was boss.

“Jess.” It was May Belle yelling from the other side of the scrap heap. “Momma says you gotta come in and eat now. Leave the milking til later.”

Oh, crud. He’d run too long. Now everyone would know he’d been out and start in on him.

“Yeah, OK.” He turned, still running, and headed for the scrap heap. Without breaking his rhythm, he climbed over the fence, scrambled across the scrap heap, thumped May Belle on the head (“Owww!”), and trotted on to the house.

“We-ell, look at the big O-lympic star,” said Ellie, banging two cups onto the table, so that the strong, black coffee sloshed out. “Sweating like a knock-kneed mule.”

Jess pushed his damp hair out of his face and plunked down on the wooden bench. He dumped two spoonfuls of sugar into his cup and slurped to keep the hot coffee from scalding his mouth.

“Oooo, Momma, he stinks.” Brenda pinched her nose with her pinky crooked delicately. “Make him wash.”

“Get over here to the sink and wash yourself,” his mother said without raising her eyes from the stove. “And step on it. These grits are scorching the bottom of the pot already.”

“Momma! Not again,” Brenda whined.

Lord, he was tired. There wasn’t a muscle in his body that didn’t ache.

“You heard what Momma said,” Ellie yelled at his back.

“I can’t stand it, Momma!” Brenda again. “Make him get his smelly self off this bench.”

Jess put his cheek down on the bare wood of the tabletop.

“Jess-see!” His mother was looking now. “And put on a shirt.”

“Yes’m.” He dragged himself to the sink. The water he flipped on his face and up his arms pricked like ice. His hot skin crawled under the cold drops.

May Belle was standing in the kitchen door watching him.

“Get me a shirt, May Belle.”

She looked as if her mouth was set to say no, but instead she said, “You shouldn’t ought to beat me in the head,” and went off obediently to fetch his T-shirt. Good old May Belle. Joyce Ann would have been screaming yet from that little tap. Four-year-olds were a pure pain.

“I got plenty of chores needs doing around here this morning,” his mother announced as they were finishing the grits and red gravy. His mother was from Georgia and still cooked like it.

“Oh, Momma!” Ellie and Brenda squawked in concert. These girls could get out of work faster than grasshoppers could slip through your fingers.

“Momma, you promised me and Brenda we could go to Millsbu

“You ain’t got no money for school shopping!”

“Momma. We’re just going to look around.” Lord, he wished Brenda would stop whining so. “Christmas! You don’t want us to have no fun at all.”

“Any fun,” Ellie corrected her primly.

“Oh, shuttup.”

Ellie ignored her. “Miz Timmons is coming by to pick us up. I told Lollie Sunday you said it was OK. I feel dumb calling her and saying you changed your mind.”

“Oh, all right. But I ain’t got no money to give you.”

Any money, something whispered inside Jess’s head.

“I know, Momma. We’ll just take the five dollars Daddy promised us. No more’n that.”

“What five dollars?”

“Oh, Momma, you remember.” Ellie’s voice was sweeter than a melted Mars Bar. “Daddy said last week we girls were going to have to have something for school.”

“Oh, take it,” his mother said angrily, reaching for her cracked vinyl purse on the shelf above the stove. She counted out five wrinkled bills.

“Momma”—Brenda was starting again—“can’t we have just one more? So it’ll be three each?”

“No!”

“Momma, you can’t buy nothing for two fifty. Just one little pack of notebook paper’s gone up to…”

“No!”

Ellie got up noisily and began to clear the table. “Your turn to wash, Brenda,” she said loudly.

“Awww, Ellie.”

Ellie jabbed her with a spoon. Jesse saw that look. Brenda shut up her whine halfway out of her Rose Lustre lipsticked mouth. She wasn’t as smart as Ellie, but even she knew not to push Momma too far.

Which left Jess to do the work as usual. Momma never sent the babies out to help, although if he worked it right he could usually get May Belle to do something. He put his head down on the table. The running had done him in this morning. Through his top ear came the sound of the Timmonses’ old Buick—“Wants oil,” his dad would say—and the happy buzz of voices outside the screen door as Ellie and Brenda squashed in among the seven Timmonses.

“All right, Jesse. Get your lazy self off that bench. Miss Bessie’s bag is probably dragging ground by now. And you still got beans to pick.”

Lazy. He was the lazy one. He gave his poor deadweight of a head one minute more on the tabletop.

“Jess-see!”

“OK, Momma. I’m going.”

It was May Belle who came to tell him in the bean patch that people were moving into the old Perkins place down on the next farm. Jess wiped his hair out of his eyes and squinted. Sure enough. A U-Haul was parked right by the door. One of those big jointed ones. These people had a lot of junk. But they wouldn’t last. The Perkins place was one of those ratty old country houses you moved into because you had no decent place to go and moved out of as quickly as you could. He thought later how peculiar it was that here was probably the biggest thing in his life, and he had shrugged it off as nothing.

The flies were buzzing around his sweating face and shoulders. He dropped the beans into the bucket and swatted with both hands. “Get me my shirt, May Belle.” The flies were more important than any U-Haul.

May Belle jogged to the end of the row and picked up his T-shirt from where it had been discarded earlier. She walked back holding it with two fingers way out in front of her. “Oooo, it stinks,” she said, just as Brenda would have.

“Shuttup,” he said and grabbed the shirt away from her.

TWO

Leslie Burke

Ellie and Brenda weren’t back by seven. Jess had finished all the picking and helped his mother can the beans. She never canned except when it was scalding hot anyhow, and all the boiling turned the kitchen into some kind of hellhole. Of course, her temper had been terrible, and she had screamed at Jess all afternoon and was now too tired to fix any supper.

Jess made peanut-butter sandwiches for the little girls and himself, and because the kitchen was still hot and almost nauseatingly full of bean smell, the three of them went outside to eat.

The U-Haul was still out by the Perkins place. He couldn’t see anybody moving outside, so they must have finished unloading.

“I hope they have a girl, six or seven,” said May Belle. “I need somebody to play with.”

“You got Joyce Ann.”

“I hate Joyce Ann. She’s nothing but a baby.”

Joyce Ann’s lip went out. They both watched it tremble. Then her pudgy body shuddered, and she let out a great cry.

“Who’s teasing the baby?” his mother yelled out the screen door.

Jess sighed and poked the last of his sandwich into Joyce Ann’s open mouth. Her eyes went wide, and she clamped her jaws down on the unexpected gift. Now maybe he could have some peace.

He closed the screen door gently as he entered and slipped past his mother, who was rocking herself in the kitchen chair watching TV. In the room he shared with the little ones, he dug under his mattress and pulled out his pad and pencils. Then, stomach down on the bed, he began to draw.

Jess drew the way some people drink whiskey. The peace would start at the top of his muddled brain and seep down through his tired and tensed-up body. Lord, he loved to draw. Animals, mostly. Not regular animals like Miss Bessie or the chickens, but crazy animals with problems—for some reason he liked to put his beasts into impossible fixes. This one was a hippopotamus just leaving the edge of the cliff, turning over and over—you could tell by the curving lines—in the air toward the sea below where surprised fish were leaping goggle-eyed out of the water. There was a balloon over the hippopotamus—where his head should have been but his bottom actually was—“Oh!” it was saying. “I seem to have forgot my glasses.”

Jesse began to smile. If he decided to show it to May Belle, he would have to explain the joke, but once he did, she would laugh like a live audience on TV.

He would like to show his drawings to his dad, but he didn’t dare. When he was in first grade, he had told his dad that he wanted to be an artist when he grew up. He’d thought his dad would be pleased. He wasn’t. “What are they teaching in that damn school?” he had asked. “Bunch of old ladies turning my only son into some kind of a—” He had stopped on the word, but Jess had gotten the message. It was one you didn’t forget, even after four years.

The devil of it was that none of his regular teachers ever liked his drawings. When they’d catch him scribbling, they’d screech about waste—wasted time, wasted paper, wasted ability. Except Miss Edmunds, the music teacher. She was the only one he dared show anything to, and she’d only been at school one year, and then only on Fridays.

Miss Edmunds was one of his secrets. He was in love with her. Not the kind of silly stuff Ellie and Brenda giggled about on the telephone. This was too real and too deep to talk about, even to think about very much. Her long swishy black hair and blue, blue eyes. She could play the guitar like a regular recording star, and she had this soft floaty voice that made Jess squish inside. Lord, she was gorgeous. And she liked him, too.

One day last winter he had given her one of his pictures. Just shoved it into her hand after class and run. The next Friday she had asked him to stay a minute after class. She said he was “unusually talented,” and she hoped he wouldn’t let anything discourage him, but would “keep it up.” That meant, Jess believed, that she thought he was the best. It was not the kind of best that counted either at school or at home, but it was a genuine kind of best. He kept the knowledge of it buried inside himself like a pirate treasure. He was rich, very rich, but no one could know about it for now except his fellow outlaw, Julia Edmunds.

“Sounds like some kinda hippie,” his mother had said when Brenda, who had been in seventh grade last year, described Miss Edmunds to her.

She probably was. Jess wouldn’t argue that, but he saw her as a beautiful wild creature who had been caught for a moment in that dirty old cage of a schoolhouse, perhaps by mistake. But he hoped, he prayed, she’d never get loose and fly away. He managed to endure the whole boring week of school for that one half hour on Friday afternoons when they’d sit on the worn-out rug on the floor of the teachers’ room (there was no place else in the building for Miss Edmunds to spread out all her stuff) and sing songs like “My Beautiful Balloon,” “This Land Is Your Land,” “Free to Be You and Me,” “Blowing in the Wind,” and because Mr. Turner, the principal, insisted, “God Bless America.”