SF: Author's Choice 4, page 1

reworking of an earlier version 7-02-2023

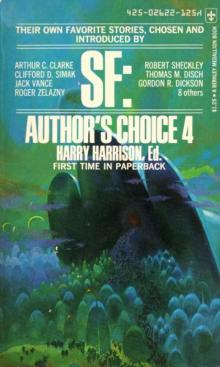

SF:

AUTHOR'S CHOICE 4

HARRY HARRISON, Ed.

Copyright © 1974, by Harry Harrison

All rights reserved

Published by arrangement with G. P. Putnam's Sons,

All rights reserved which includes the right

to reproduce this book or portions thereof in

any form whatsoever. For information address

G. P. Putnam's Sons

200 Madison Avenue

New York, New York 10022

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 74-11615$

SBN 425-02622-1

BERKLEY MEDALLION BOOKS are published by

Berkley Publishing Corporation

200 Madison Avenue

New York, N.Y. 10016

BERKLEY MEDALLION BOOKS ® TM 757,375

PRINTED IN CANADA

Berkley Medallion Edition, AUGUST, 1974

Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION - Harry Harrison

OLD HUNDREDTH -Brian W. Aldiss

FAIR - John Brunner

THE FORGOTTEN ENEMY - Arthur C. Clarke

WARRIOR - Gordon R. Dickson

ET IN ARCADIA EGO - Thomas M. Disch

BUT SOFT, WHAT LIGHT. - Carol Emshwiller

THE MISOGYNIST - James Gunn

ALL OF US ARE DYING - George Clayton Johnson

THE FIRE AND THE SWORD - Frank M. Robinson

BAD MEDICINE - Robert Sheckley

THE AUTUMN LAND - Clifford D. Simak

A SENSE OF BEAUTY - Robert Taylor

THE LAST FLIGHT OF DR. AIN - James Tiptree, Jr.

ULLWARD’S RETREAT - Jack Vance

THE MAN WHO LOVED THE FAIOLI - Roger Zelazny

SF: AUTHOR'S CHOICE 4

“Old Hundredth,” by Brian W. Aldiss, copyright © 1960 by Brian W. Aldiss; reprinted by permission of the author.

“Fair,” by John Brunner, copyright © 1956 by Nova Publications Ltd.; reprinted by permission of Brunner Fact & Fiction Ltd.

“The Forgotten Enemy,” by Arthur C. Clarke, copyright © 1949 by Nova Publications Ltd.; reprinted by permission of the author and the author’s agents, Scott Meredith Literary Agency, Inc.

“Warrior,” by Gordon R. Dickson, copyright © 1965 by Conde Nast Publications, Inc.; reprinted by permission of the author and the author’s agent, Robert P. Mills, Ltd.

“Et In Arcadia Ego,” by Thomas M. Disch, copyright © 1971 by Coronet Communications, Inc.; reprinted by permission of the author and Brandt & Brandt.

“But Soft, What Light . . .” by Carol Emshwiller, copyright © 1966 by Mercury Press, Inc.; reprinted by permission of the author and the author’s representative, Virginia Kidd.

“The Misogynist,” by James Gunn, copyright © 1952 by Galaxy Publications, Inc.; reprinted by permission of the author.

“All of Us Are Dying,” by George Clayton Johnson, copyright © 1961 by Greenleaf Publishing Co.; reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Fire and the Sword,” by Frank M. Robinson, copyright © 1951 by Frank M. Robinson; reprinted by permission of the author.

“Bad Medicine,” by Robert Sheckley, copyright © 1957 by Robert Sheckley; reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Autumn Land,” by Clifford D. Simak, copyright © 1971 by Mercury Press, Inc.; reprinted by permission of the author and the author’s agent, Robert P. Mills, Ltd.

“A Sense of Beauty,” by Robert Taylor, copyright © 1968 by Mercury Press, Inc.; reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Last Flight of Dr. Ain,” by James Tiptree, Jr., copyright © 1969 by UPD Publishing Corporation; reprinted by permission of the author and the author’s agent, Robert P. Mills, Ltd.

“Ullward’s Retreat,” by Jack Vance, copyright © 1958 by Galaxy Publishing Corp.; reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Man Who Loved the Faioli,” by Roger Zelazny, copyright © 1967 by Galaxy Publishing Corp.; reprinted by permission of the author and his agents, Henry Morrison Inc.

INTRODUCTION - Harry Harrison

In the first Authors Choice volume, Theodore R. Cogswell wrote this comment:

The only memory I have of writing any of my stories is that what took place seemed to me to be an inevitable process . . . Writing is seduction. And I’ve never quite decided who is doing what and to whom.

He went on in greater detail to assure the friendly reader that it was impossible to tell anything about a story that was not already there in the story itself. Yet in this same anthology Philip Jose Farmer wrote a description of the background and preparation for writing his story that was three-quarters as long as the story he was writing about.

In case you are beginning to get the feeling that authors are an individualistic, withdrawn, outgoing, quiet, noisy, unthinking, intellectualizing bunch of people—why you are completely right. You have to be an individualist to be a writer as these comments prove over and over again. The name of the game we are trying to play here is insight; we are attempting to pin down some factor or factors in the act of creation that will add new dimensions to the stories themselves. The authors have been asked to contribute a story they feel particularly fond of, not necessarily their favorite story but one upon which they look with a feeling of some warmth. They were particularly encouraged to uncover stories they felt should have been anthologized and that have been overlooked by the dim-witted editors. Once these stories were selected each author then had complete freedom to say just what he wanted about it including, as in the case of Mr. Cogswell, the observation that the whole thing is a foolish and impossible task.

This series started in a small way. The first volume was filled with stories by writers whom I knew and respected, whom I wanted to pin down to some description of the creative process. The results were so satisfying that other volumes followed. There are enough good and professional authors in the field of science fiction to fill far more than that single book, and while I cannot claim to have captured every one of them, I have managed to run a large percentage to earth. There is no particular sequence to the volumes other than that I have tried, in each of them, to balance new authors against old practitioners in order to give a more complete spectrum of the writing being done in science fiction today. In this present anthology we have the celebrated Arthur C. Clarke balanced against the rising star of James Tip-tree, Jr. Though balance is an unfair word. They are both laborers in our particular stainless steel vineyard. It was E. M. Forster who, while writing on the art of the novel, visualized all of the novelists of history as writing away at the same time in the reading room of the British Museum. Certainly it is a valid image, since books are shelved together and read at the same time no matter what their age. The same is true of science fiction. H. G. Wells was a nineteenth-century author, yet I recently saw one of his novels in the drugstore nestled against a short story collection of Brian W. Aldiss. I don’t think either of them suffered from the association and the proximity.

So while the novelists scribble away in the British Museum, the science fiction writers are also hard at work—but where? Perhaps in the cabin of some great spaceship with the stars of interstellar space shining through the portholes like those familiar holes in a blanket. I have tiptoed around this cabin and disturbed a few of those hard at work here and have asked them to take a look at their labors and to tell us about it.

Here is what they said.

Harry Harrison

OLD HUNDREDTH -Brian W. Aldiss

The whole human cavalcade is slowly on its way to the future, numbers swelling as it goes. Year by dusty year, the cavalcade grows noisier, while the innocent creatures dwelling in its track have more and more cause to be anxious about its depredations.

Where is it going? How long has it got to reach its unknown goal? And those who reach the goal—what relationship will they bear to those who set out blindly so many generations before?

These profound questions await answer. As yet, we can hardly understand them, even when they are applied to our own individual lives. But a writer may be allowed to sketch some sort of tentative answer now and again.

I have no religious faith. Unfortunately, I have a profoundly religious sense of life, and can’t break the habit. Even when I was a child, I found myself viewing what went on about me sub specie aeternitatis. This may sound like a case of alienation, but the fact is that nowadays—it would be unfair to speak up for that silent and long-vanished child—I enjoy a strong sense of being part of the flows and tides of Earth.

In our generation, we are accustomed to thinking of Earth as a kind of spaceship which uses the sun as power-source while recycling all its abundant but not infinite resources. The stuff of which we are made, and the natural world about us, is a recombination of the stuff of which the early amoebae in the primordial ocean, the lowly plants which first covered the land, the slow dinosaurs, the men of the Stone Age, the Angles, Saxons, and

Jutes, and Uncle Tom Cobblelgh and all were made. Everything that once existed now exists. From this it follows that we also will inevitably be ground down to provide the basic ingredients for new recipes of life throughout the remaining millions of years of Earth’s history. And all our science and technology, on which we place such great store, is not going to alter the situation.

A sense of this large harmony is what I tried to impart in “Old Hundredth,” using a veritable old harmony at the centre of the story to give body to my

As the critic Edmund Crispin has observed, I have a special feeling for the autumnal, and “Old Hundredth” is, in his words, “a dream of the last long autumn of Earth” (I think American readers would agree that the word “fair would be misleading here). Much else that Crispin says about the story is too flattering to be quoted; but I may add that it was one that gave me pleasure even before he favoured it with his commendation, perhaps because I came somewhere near to achieving what I was attempting.

Although I was trying to make everything old and dusty and—we need a word for Bygone-in-the-future—I was aiming at joy, rather in the way that C. S. Lewis gets joy into his novel Out of the Silent Planet, and in a strange fashion joy does still move like a serpent through the paragraphs—for me at least, rereading it before sending off a copy to Editor Harrison for the latest volume in his series.

To be more prosaic about the subject. The title originally had a double meaning. Ted Carnell wrote to me in 196o asking for a special contribution to the centennial number of New Worlds which he edited. I wanted to write an especially appropriate something, and the title “Old Hundredth” immediately came bubbling to the surface and would not go away.

Good old Ted! Nobody else could have performed his mammoth task of making bricks with so little straw as he did for so long. He had every reason to celebrate his long haul to Number 100. No other British magazine lived so long. He paid on acceptance, too, and I got a check for ten pounds sterling on May 25, 1960. The story was anthologized in that year’s Best SF, edited by Judy Merril (remember Judy Merril?), when it earned rather more than ten pounds. Since then, it has been reprinted half-a-dozen or so times.

It’s just an animal story. But in the background you can hear the murmur of the human cavalcade.

—Brian W. Aldiss

The road climbed dustily down between trees as symmetrical as umbrellas. Its length was punctuated at one point by a musicolumn standing on the sandy verge. From a distance, the column was only a faint stain in the air. As sentient creatures neared it, their psyches activated it, it drew on their vitalities, and then it could be heard as well as seen. Their presence made it flower into pleasant noise, instrumental or chant.

All this region was called Ghinomon, for nobody lived here any more, not even the odd hermit Impure. It was given over to grass and the weight of time. Only a few wild goats activated the musicolumn nowadays, or a scampering vole wrung a brief chord from it in passing.

When old Dandi Lashadusa came riding down that dusty road on her baluchitherium, the column began to intone. It was just an indigo trace on the air, hardly visible, for it represented only a bonded pattern of music locked into the fabric of that particular area of space. It was also a transubstantio-spatial shrine, the eternal part of a being that had dematerialized itself into music.

The baluchitherium whinnied, lowered its head, and sneezed onto the gritty road.

“Gently, Lass,” Dandi told her mare, savouring the growth of the chords that increased in volume as she approached. Her long nose twitched with pleasure as if she could feel the melody along her olfactory nerves.

Obediently, the baluchitherium slowed, turning aside to crop fern, although it kept an eye on the indigo stain. It liked things to have being or not to have being; these half-and-half objects disturbed it, though they could not impair its immense appetite.

Dandi climbed down her ladder onto the ground, glad to feel the ancient dust under her feet. She smoothed her hair and stretched as she listened to the music.

She spoke aloud to her mentor, half the world away, but he was not listening. His mind closed to her thoughts, he muttered an obscure exposition that darkened what it sought to clarify.

“. . . useless to deny that it is well-nigh impossible to improve anything, however faulty, that has so much tradition behind it. And the origins of your bit of metricism are indeed embedded in such a fearful antiquity that we must needs—”

“Hush, Mentor, come out of your black box and forget your hatred of my ‘metricism’ a moment,” Dandi Lashadusa said, cutting her thought into his. “Listen to the bit of metricism’ I’ve found here, look at where I have come to, let your argument rest.” She turned her eyes about, scanning the tawny rocks near at hand, the brown line of the road, the distant black and white magnificence of ancient Oldorajo’s town, doing this all for him, tiresome old fellow. Her mentor was blind, never left his cell in Peterbroe to go farther than the sandy courtyard, hadn’t physically left that green cathedral pile for over a century. Womanlike, she thought he needed change. Soul, how he rambled on! Even now, he was managing to ignore her and refute her.

“. . . for consider, Lashadusa woman, nobody can be found to father it. Nobody wrought or thought it, phrases of it merely came together. Even the old nations of men could not own it. None of them knew who composed it. An element here from a Spanish pavan, an influence there of a French psalm tune, a flavour here of early English carol, a savour there of late German chorals. Nor are the faults of your bit of metricism confined to bastardy . . .”

“Stay in your black box then, if you won’t see or listen,” Dandi said. She could not get into his mind; it was the Mentor s privilege to lodge in her mind, and in the minds of those few other wards he had, scattered round Earth. Only the mentors had the power of being in another’s mind—which made them rather tiring on occasions like this, they would not get out of it. For over seventy years, Dandi’s mentor had been persuading her to die into a dirge of his choosing (and composing). Let her die, yes, let her transubstantio-spatialize herself a thousand times! His quarrel was not with her decision but her taste, which he considered execrable.

Leaving the baluchitherium to crop, Dandi walked away from the musicolumn towards a hillock. Still fed by her steed’s psyche, the column continued to play. Its music was of a simplicity, with a dominant-tonic recurrent bass part suggesting pessimism. To Dandi, a savant in musicolumnology, it yielded other data. She could tell to within a few years when its founder had died and also what kind of a creature, generally speaking, he had been.

Climbing the hillock, Dandi looked about. To the south where the road led were low hills, lilac in the poor light. There lay her home. At last she was returning, after wanderings covering half a century and most of the globe.

Apart from the blind beauty of Oldorajo’s town lying to the west, there was only one landmark she recognized. That was the Involute. It seemed to hang iridal above the ground a few leagues on; just to look on it made her feel she must at once get nearer.

Before summoning the baluchitherium, Dandi listened once more to the sounds of the musicolumn, making sure she had them fixed in her head. The pity was her old fool wise man would not share it. She could still feel his sulks floating like sediment through his mind.

“Are you listening now, Mentor?”

“Eh? An interesting point is that back in 1556 by the old pre-Involutary calendar your same little tune may be discovered lurking in Knox’s Anglo-Genevan Psalter, where it espoused the cause of the third psalm—”

“You dreary old fish! Wake yourself! How can you criticize my intended way of dying when you have such a fustian way of living?”

This time he heard her words. So dose did he seem that his peevish pinching at the bridge of his snuffy old nose tickled hers too.

“What are you doing now, Dandi?” he inquired.