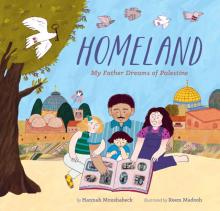

Homeland, page 1

To refugees around the world and all those displaced from their homelands. —HM

To my loving family. And to my grandparents. Thinking of you, always. —RM

Text copyright © 2023 by Hannah Moushabeck.

Illustrations copyright © 2023 by Reem Madooh.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available.

ISBN 9781797202051 (hc), 9781797203607 (epub2), 9781797225913 (epub3), 9781797225906 (Kindle)

Design by Mariam Quraishi.

Typeset in Klinic Slab.

The illustrations in this book were rendered digitally.

Chronicle books and gifts are available at special quantity discounts to corporations, professional associations, literacy programs, and other organizations. For details and discount information, please contact our premiums department at corporatesales@chroniclebooks.com or at 1-800-759-0190.

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, California 94107

Chronicle Books—we see things differently.

Become part of our community at www.chroniclekids.com.

We wait in bed for our father to come home from work. We know he’s coming when we hear the coins jingle in his pockets as he walks up the stairs.

Sometimes he whistles us to sleep. Sometimes he tells us stories.

We like the stories best.

There’s the story about how he fed his neighbor Muhammad so many beans that he farted powerfully enough to lift off the ground.

And there are stories about our homeland, a place we’ve never been.

Every summer my father visited his grandparents Teta Maria and Sido Abu Michel, who lived in the Old City of Jerusalem. The final day of one visit started with his favorite breakfast, ka’ek.

Teta Maria called through the window to a street vendor below. She dropped a basket on a rope, and up it came—delicious bread, still warm. No matter how much food my father ate, Teta Maria always told him, “Eat more, habibi!”

His sido was a stern-looking, tarboosh-wearing, argileh-puffing, mustachioed man. He was always busy with grown-up matters. But this bright morning Sido announced that together the two of them would visit the family café.

Walking through the streets of East Jerusalem, my father and his sido stopped every few paces to greet people and tell stories. Abu Michel was called al-Mukhtar, the head of the community, and he spoke many languages.

They walked hand in hand through a bustling collection of colorful vendors. Men and women sold everything from olive oil soap with rose water and heaping bags of za’atar to gold jewelry and embroidered textiles.

As they walked, they were serenaded by sounds: the chanting of the muazzin’s call to prayer mixed with the ringing of church bells and the market vendors singing the praises of pickling cucumbers or prickly pears.

They could hear the cheerful sounds of children practicing dabke dancing and the songs of Oum Koulthoum that blasted from radios on windowsills.

But what fascinated my father most was the juice vendor! A short man, he carried a big tank filled with jellab on his back. He traveled by foot from neighborhood to neighborhood. To announce his arrival, he played beautiful, intricate rhythms, using brass cups and saucers.

To his teta’s horror, my father later practiced these same rhythms at home, using her china.

Now a professional drummer, he shows me and my sisters the juice man’s rhythms by drumming on our backs, like a musical massage.

At the family café, my father was greeted quickly with one kiss on each cheek by Amo Mitri. He was then put to work cutting cucumbers, chopping parsley, and preparing plates of olives and pink pickled turnips.

The café was a popular destination for great thinkers. Poets, musicians, historians, and storytellers gathered to listen to the exchange of ideas at al-Mukhtar’s café.

With a rare smile, Sido signaled to my father to follow him down a hallway. Sido unlocked the iron gate and led him to a lush, sunlit garden. Hundreds of homing pigeons rustled in their wooden cages in the shade of a proud olive tree.

The next moment, he released all the pigeons and skillfully guided them into a circle in the sky, with the help of only a black piece of cloth tied to the end of a long stick.

With surprise and delight, my father asked, “Won’t they fly away?”

Sido shook his head slowly, the key swaying at his side. “This is their home.”

That was the last day my father saw his grandfather; the last time he saw Palestine.

Our eyes are heavy with sleep, but we want to hear more. “Show us the key!” we cry. My father produces the large, rusted old key to our family’s home in Jerusalem. We know the ending of this story is not a happy one. We know that we may never sit and watch the juice man by Jaffa Gate. But we whisper the hope of return as we turn out the light.

At night we dream of our homeland.

Glossary

Teta [Teh∙tah] and sitti [sit∙tee] are Arabic words for grandmother. Teta is what I call my grandmother.

jiddo [jed∙do] and Sido [See∙doo] are Arabic words for grandfather. Jiddo is what I call my grandfather, and it is what my nieces and nephews call my father.

Abu [A∙boo] means father of. In the Arab world it is common to refer to someone as Abu and then the name of their eldest child. My great-grandfather was referred to as Abu Michel because his eldest son, my grand-father, was named Michel.

KA’EK [Ka∙Eh∙k] is a baked good that looks like a flattened bagel with sesame seeds and a big hole in the middle. Ka’ek vendors display dozens of these loaves in trays that they balance on their heads.

Habibi [Ha∙bee∙ bee] (masculine) and Habibti [Ha∙ bee∙tee] (feminine) mean my love or darling but can often be used in a casual exchange to stand in for my friend. These are among the most common words used in conversational Arabic.

Yalla [YAL∙LAH] means come on, let’s go, or hurry. Arab Americans say “Yalla, bye” when they are saying goodbye quickly (goodbyes usually take a long time for Arabs).

A tarboosh [tar∙boo∙sch], sometimes called a fez, is a red felt hat, often with a black tassel, worn by men in the Middle East.

An argileh [ar∙gee∙lay] is a water pipe that uses a long tube and hot coals to draw flavored tobacco through water. It is also known as a hookah or shisha.

A mukhtar [mook∙tar] is a leader of a town or government. My father’s grandfather was head of the Eastern Orthodox Christian Arab community in Jerusalem.

Za’atar [Za∙tar] is a wild variety of oregano that grows all over the Levant. It is the main ingredient in a popular Middle Eastern spice mixture of the same name, which is made up of the dried crumbled herb, sumac, and toasted sesame seeds.

A muAzzin [mo∙a∙Zen] is a person who calls Muslims to prayer, through speakers or from the minaret of a mosque.

Dabke [Dab∙kah] is an Arabic folk dance in which people line up, often holding hands, and perform a combination of hops and stomps. Dabke is usually a dance of celebration and takes place at events such as weddings and parties.

Oum Koulthoum [UMm∙Kul∙thoom] was a legendary singer, songwriter, and actress. She is the most famous singer in the Middle East, having sold over 80 million records. To this day she is a treasured icon across the world.

A kaffiyeh [ko∙fee∙yeh] is a square scarf with checkered embroidery, worn around the head or neck to offer protection from the sun. Kaffiyehs are worn by both Arabs and non-Arabs as a symbol of Palestinian solidarity and resistance.

Jellab [Jal∙lab] is a sweet brown drink made from carob, dates, grape molasses, and rose water, topped with pine nuts.

Tatreez [Tut∙reez] is a colorful, intricate cross-stitch embroidery style. It has been used in Palestine for over 3,000 years.

Author’s note

My sisters and I grew up hearing stories of our homeland from our mother, father, aunts, and uncles. Sometimes I learned my history at family gatherings, when the grown-ups became nostalgic and argued about how we were related to various people—“No, you are second cousins on both sides, not first cousins on one side!” My family laughed about old stories between the hard times—and during, too. Sometimes stories were told to my mother by my father’s mother, a bond between women, secrets meant to be passed like recipes to her daughters. Someday I hope to pass these stories on to my own children, just like I’m sharing this one with you.

The stories told to me and my sisters before bed, in the room we shared, were the best. In the same night, we would hear a tale of a hero climbing a tower to rescue a magical princess, and then we would learn about our father as a boy, skillfully evading grumpy priests and stealing sweets from his teta’s kitchen. Now it’s hard to remember which were fairy tales and which were true, as the stories blend together and our homeland feels more and more like a magical place.

My family lived in the Katamon neighborhood in West Jerusalem until May 15, 1948, the day Palestinians call Al-Nakba, or the catastrophe. On this day all my relatives, after being warned of danger, packed small bags, locked their doors, piled into my grandfather’s car, and took sanctuary in the Greek Orthodox Monastery next to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in East Jerusalem. They were never allowed to return to their homes and, to this day, carry with them the keys to their houses, now occupied by others. As the mukhtar, my great-grandfather was permitted to live at the convent until he died. My relatives, including my father, visited the

Issa Michael Rofao Toubbeh (known as Sido, the Mukhtar, or Abu Michel) in Palestine, 1960s

Hannah and her father, Michel, in Brooklyn, 1987

Hannah’s father, Michel Simon Moushabeck, sitting on the stoop of his Uncle Fakhri and Aunt Almaza’s house located just outside Jerusalem, 1966

Hannah, Leyla, and Maha Moushabeck in their home in Brooklyn, 1991

Reem Madooh is an illustrator from Kuwait with an MA in Children’s Book Illustration. She is an avid picture book collector and loves narrative storytelling and incorporating a dreamlike atmosphere into her art. As a child, she enjoyed listening to stories of the old days from her parents and grandparents. She also loves za’atar and makes sure to have some every day. Homeland: My Father Dreams of Palestine is her first picture book. She lives in Kuwait.

Hannah Moushabeck is a second-generation Palestinian American author, editor, and marketer who was raised in a family of book- sellers and publishers in Western Massachusetts and England. Born in Brooklyn into Interlink Publishing, a family-run independent publishing house, she learned the power of literature at a young age. Homeland: My Father Dreams of Palestine is her first picture book. She lives in Amherst, Massachusetts, on the homelands of the Pocumtuc and Nipmuc Nations.

Hannah Moushabeck, Homeland

Thanks for reading the books on GrayCity.Net