No Life for a Lady, page 1

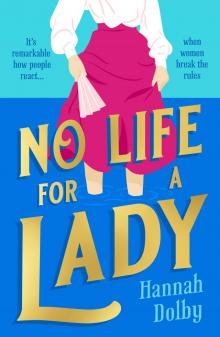

NO LIFE FOR A LADY

NO LIFE FOR A LADY

Hannah Dolby

www.headofzeus.com

First published in 2023 by Head of Zeus, part of

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Copyright © Hannah Dolby, 2023

The moral right of Hannah Dolby to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This is a work of fiction. All characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN (HB): 9781804544365

ISBN (XTPB): 9781804544372

ISBN (E): 9781804544341

Cover design: Nina Elstad

Head of Zeus

First Floor East

5–8 Hardwick Street

London EC1R 4RG

WWW.HEADOFZEUS.COM

To my mother, Ann Grace – my rock and my inspiration for joy, creativity and laughter

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Chapter Forty-Two

Chapter Forty-Three

Chapter Forty-Four

Chapter Forty-Five

Chapter Forty-Six

Chapter Forty-Seven

Chapter Forty-Eight

Chapter Forty-Nine

Chapter Fifty

Chapter Fifty-One

Chapter Fifty-Two

Chapter Fifty-Three

Chapter Fifty-Four

Chapter Fifty-Five

Chapter Fifty-Six

Chapter Fifty-Seven

Chapter Fifty-Eight

Chapter Fifty-Nine

Chapter Sixty

Chapter Sixty-One

Chapter Sixty-Two

Chapter Sixty-Three

Chapter Sixty-Four

Chapter Sixty-Five

Chapter Sixty-Six

Acknowledgements

About the Author

An Invitation from the Publisher

Prologue

It was hot, the night my mother disappeared.

It was a Saturday, and she had been going out. I had wanted to go out with her, because I was eighteen, and bored, and because the world and my exciting future beckoned.

‘You can’t come this time, Vi,’ she said, stroking my hair. ‘When you’ve had your debut, perhaps. Then I can take you to a few parties, we can have fun. Girls together.’ She was wearing a dress in dark green silk, her hair tangled up with sprigs of flowers and a scattering of ruby pins, and she smelt like gardenias or some other exotic bloom.

‘Where are you going?’ I asked, because she had as ever been vague.

‘Just to see a few friends. Nothing dramatic. I will probably be bored.’ She yawned, and stretched out her feet, examining her silk evening slippers. ‘No dancing, I hope.’

‘You look beautiful,’ I said, because it was expected and also true.

‘It’s not all it’s cracked up to be, this beauty lark,’ she said. ‘A lot of the time it’s more trouble than it’s worth. Just be glad that you don’t have to put up with it.

‘I don’t mean it like that,’ she rushed to say, seeing my face. ‘You are just as beautiful as me, when you sparkle, and make funny jokes. We all love, love, love your jokes. Your personality makes you gorgeous. I just mean that it can be a trap, too. People want too much from me. It’s not all good. But you are my beautiful, funny, sweet little daughter and I love you.’ She grabbed me in her arms and squashed me tight, while I resolved to give up my role as comedy daughter.

These scenes of lamentation were not new, but I did wish she would stop using me as a comparison.

‘I should like to do something useful in life,’ I said, when she had released me. ‘Something that could perhaps earn money. Do you think there might be a way?’

‘There are always ways, but it’s not easy,’ she said. ‘There is a gazette, I think though, that has ideas for employment for women. Interesting ideas, like book binding, or botany. Let me have a think. But don’t you want to get married?’

‘Not quite yet,’ I said.

‘Well then, I must be away!’ she said. ‘They are expecting me half an hour ago. Enjoy your evening, my Vi.’

She wafted out of the door, and that was the last time I saw her. There had been no sign from her that she might leave, no real difference in her behaviour to make me suspect she planned to go away.

That was why it would be easier to think her dead. But even now, ten years on, I could not let her go.

Chapter One

I first suspected I had hired the wrong detective when he gently stroked the photograph of my mother with his thumb.

‘Attractive lady,’ he said. ‘Hastings pier, you say? When was it?’ He laid the picture down beside the pile of pound notes I had given him and stared at it. ‘You don’t look like her.’

‘It was ten years ago, the summer of 1886. No, I don’t,’ I said.

He was dressed in a puce and yellow striped blazer and a straw boater, as if he should be strolling along the beach instead of sitting behind a desk. It was no reason to dismiss a successful man of business, but my instinct was a live creature, squealing at me to leap off my chair and scurry out.

I stayed because I had dreamt of hiring a detective for a long time. His advertisement in the Hastings Observer promised, in splendidly large capital letters, to deal with investigations with discretion and valour. His office was in a smart glass-fronted shop on the St Leonards’ Colonnade, on the very finest stretch of the Marine Parade, and he had a shining brass pen and inkstand on his well-varnished desk. These things should inspire confidence.

‘Lily, Lily Hamilton.’ He scrawled it on a sheet of paper and circled it twice. ‘And the disappearance was in the newspapers? What did the police say?’

I realised I was clutching the edge of my chair, so I loosened my hands and smoothed them flat across my skirts. ‘Yes, it was in the local newspapers. I don’t think it went further. The police did not investigate for long. They thought she had left us, and my father agreed.’

‘Where is your father today?’

‘He does not need to be involved,’ I said, firmly. The man looked at me with a small smile and his moustache, sleek and rat-brown coloured, smiled along with him.

‘To be frank,’ he said, and that was silly, because he was Frank – ‘Frank Knight’, the sweep of gold lettering said on the window behind me, ‘Detective’. A name full of hope, of chivalrous adventure and pioneering spirit; now of slowly deflating dreams. ‘There are ladies who don’t like what they are made for, the cleaning and the domestic business, the caring and the mothering. We might think badly of them for it, but it does happen.’

A philosopher, then. ‘I don’t think she would have wanted to leave,’ I said. I could not talk about love to this man. ‘I think she would have let me know. She—’

‘And it’s such a long time,’ he said. ‘Ten years? She will have a whole new life by now, started again somewhere else. A lady who looks like that, could.’ He looked past me out of the window, at the bustle of carriages and the gaggles of people thronging the promenade. Outside I could hear chatter and laughter as well as the cries of seagulls and, distantly, the squabbles of a Punch and Judy show. ‘If she’s alive, that is. If she drowned, well, of course, that’s tragic. It is surprising she didn’t wash up somewhere along the coast, though.

‘What age are you, twenty?’ he said to the window behind me. ‘You should be thinking about your own life, not raking up the past. Creating your own brood.’

It had been a mistake to come without a chaperone. ‘I am twenty-eight, and not inclined to marry,’ I said. It sounded grown-up, until I said it aloud. ‘Will you take my case?’

<

‘Of course, Miss Hamilton. Happy to help a lady in trouble. I’m in the middle of another case, so I can’t be doing anything else for a week or two, but it’s waited this long, hasn’t it? She’s a lady – not that you’re not one,’ he added. ‘Only that she is a real lady. Of means, I mean. And there are a lot of men – she needs a lot of men – there isn’t the resource immediately. But Frank Knight is not one to leave a wilting flower without water.

‘Tell me about your mother.’ He leant forward in his chair with a creak of leather. ‘Was she happy at home? Any arguments, domestics? Was she the faithful kind? How was she dressed when she disappeared? Did she have enemies?’ He spread his fingers out flat on the desk, starlike, and waited.

It was not how I had imagined a detective’s office should be. The room was cavernous, his desk and our two chairs the only furniture in it. The walls were lined with shelves from floor to ceiling, all empty, and the surface of his desk held only a single sheet of paper, an unused blotting pad and the pen and inkstand. It was as if he had wandered in and set up office that morning, on a whim.

But I had been dreaming of finding my mother for ten years and searching for a detective for two. The advertisement, and then a leaflet posted through our front door only last week, signalled fate might finally be on my side. It was no time to take fright.

‘Can you tell me how you will conduct the investigation?’ I asked. He looked taken aback.

‘You needn’t concern yourself,’ he said. ‘You can leave it all safely with me. I will follow a well-trodden path. I have years of experience. Just tell me what I need to know and then you can get back to being a young lady again. This must have been a distressing time for you, but now you can leave everything in my hands, and relax.’

He stroked the picture again with the tips of his fingers, smoothing it.

‘It would be useful to know your plans,’ I said. I was not normally argumentative, but I did not want to hand over the baggage of my life without knowing what he would do with it.

He sighed. ‘A lady who knows her own mind. Well then, here’s a new idea. A sign on the side of a building. We could use the brightest of the new paints, vermilion, pink, gold.’ He flashed his fingers as he mentioned each colour, like a magician, and then stretched his arms out full width, embracing the room. ‘I can see giant letters saying “missing person”. Something everyone sees and no one can pass by. Eight feet tall. The signwriter might even be able to catch a likeness of your mother. “Lily Hamilton, Missing”. Publicity is everything these days. That’ll stir things up, bring out the rats.’

‘No,’ I said. ‘No. This has to be discreet. You said in your advertisement, in both your advertisements, all cases of a private nature would be discreetly investigated. It’s very important to me. I don’t want any signs, or publicity. No publicity.’

He frowned and scratched the back of his head. ‘When I said leave it in my hands,’ he said, ‘I meant leave me to it. Seems you’ve been fretting too long, and you’ve forgotten that this is a man’s business. Tell me about her.’

‘I must ask you to be discreet. I would prefer that society generally does not know about this investigation. And I do not want my father to know,’ I said. A smile slipped onto his face again.

‘Indeed? Well, then, I suppose I can keep it quiet, for a lady’s sake. I’ll have to ask questions, of course. Of the police, etcetera. But I’m good at keeping secrets. Very well, no sign, although it would have moved things along more speedily. Now, to your mother.’

‘She was happy,’ I said. ‘She was happy, and all was well with her and with our lives. There was no reason for her to go. She was wearing a green silk dress. There was nothing on the day it happened to suggest she would leave. Everyone who knew her, loved her. Can I have the photograph back? It is the only one I have.’

It was not true but, for a reason I could not explain, I did not want him to have it. I reached across the desk and took it, but he lunged over and snatched it back. He was not a tall man, so it was a dramatic lunge.

‘No, I need it,’ he said, and as he sat back down again his arm knocked over his inkstand and black ink flooded over the desk, dripping off the edge onto his lap. ‘Christ,’ he said, leaping up again. He shoved the photo in his breast pocket, grabbed sheets of paper from his blotting pad and tried to stem the spill.

‘I am sorry,’ I said. ‘For, for…’ I looked away because he was blotting the front of his trousers. ‘Perhaps I should leave you to…? Is that enough for today? Shall I come back?’

‘Christ,’ he said again. He was wearing white flannels, so it would stain. ‘Yes. Leave it, I’ll sort the preliminaries, look out the newspaper cuttings, and then we can speak again in a week. I’ll need a full and frank account, though. A proper warts-and-all discussion. You can’t go missish on me, if you want me to find your mother.’

‘I shall endeavour not to be missish,’ I said, and I rose and left him there, dabbing at his trousers.

*

So it was done. I had taken a step, a terrifying step, to find out what happened the night my mother disappeared. I felt sick and exhilarated. It had not gone as I had pictured, and he was not the Mr Frank Knight I hoped for, but at least life was moving forward, as it should. For too long I had felt pinned to the past, a butterfly on a board.

To my right was the beach, dotted with bathing carriages and day-trippers, and beyond it lay the blue sea, glinting silver in the sunshine. To my left was the grand row of apartments that ran the length of the promenade, as far as the eye could see, and behind them, rising up on the hills, the fine houses of Hastings and St Leonards and, higher, the castle ruins.

It was early April, and although the wind was sharp the Marine Parade was already packed. As I spun round to walk home a seagull flew past my hat, almost dislodging it, and a small boy dressed in a sailor suit dropped his ice-cream cornet at my feet and wailed. His mother sent me a glare and hustled him on.

The woman on the seashell stand shouted, ‘Queen Conch! Sea urchin! Giant cowrie! Mother-of-pearl!’ at passersby, briefly drowned out by a one-man band, who marched along crashing his assorted musical instruments in painful discord. A goat bleated past, pulling a smartly dressed little girl in a goat-chaise, but it was not a biddable animal, and it lunged to the left, aiming for the fish and chip stand, and the girl shrieked as if her life would end.

People were lured here by the promise of free fresh air, but smells of fish, seaweed, burning wood and popcorn drifted on the breeze. There were many fine ladies out promenading, as well as several gaudy-blazered gentlemen. It was definitely the start of the new season.

Just past the rows of pleasure boats, I saw the Misses Spencer coming towards me. Of even height, as if nature had decided on perfect symmetry; dressed prettily in pale green from head to toe. I saw the second they spotted me, the panic in their eyes as they decided what to do. It was too narrow and crowded a path to leave a wide berth, so they turned sharply right, tilting their parasols in front of their faces, just before I reached them.

It was not new. They had been doing it for the last ten years, as if I had an infection that would make their mother disappear too. It did not sting so much as it had. I carried on, comforting myself with the knowledge their turn led them directly towards the gentlemen’s entrance of the public convenience.

The Misses Spencer and I had attended the same school from the ages of eleven to sixteen; a small school run by over-frilled ladies who prepared us most passionately for a destiny of flower-arranging and découpage. The Misses Spencer – Janice? Mavis? – two years or so younger than me, close to each other in age, were not unfriendly but were prematurely prissy, perfectly moulded for the world they were to enter. I had not encouraged friendship much, to be fair. I had been too excited by life and its possibilities, which then had seemed to stretch as far as the horizon and as high as the clouds. Once I had used the school’s entire supply of green and red thread to embroider a dragon, fire pouring from its nostrils, a small heap of mutilated people at its feet. The sewing instructor had warned my mother about my bloodthirsty sensibilities, but my mother had only laughed. ‘Let her embroider dragons while she can,’ she had said.