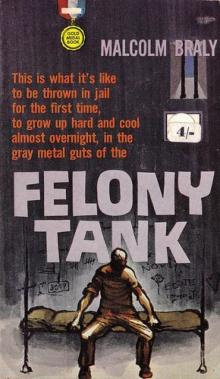

Felony Tank, page 7

He bent the word “funny” so Doug couldn’t miss the meaning. One of the jailers standing behind him snickered. The captain glared him into silence, but Doug still felt his face filling with embarrassment rising out of some obscure humiliation that his appearance should create such a suggestion. He couldn’t answer, but stood hearing the whine of the fan.

The captain read his silence for sullenness, and complained to the sergeant about how all these brats thought they were so damn tough. His words had the worn ring of a familiar complaint, but Doug took confidence from them. It was refreshing to be thought of as tough. He leveled his eyes up to meet the captain’s and put his hands in his pockets, already framing snatches of sentences to describe the scene to Agnes—how he hard-assed the captain.

But the captain didn’t hard-ass worth a damn. He reduced Doug to a mumble with a series of shrewdly related questions: Where was his cup? Who did he give it to? Who was he protecting? Did he know that the Mexican had described his attacker? That they already knew who it was?

Doug made his mistake after the last question. He muttered something to the effect that if they knew who it was why should he have to tell them

“What?” the captain demanded. “What was that?”

“If you know already, why are you asking me?”

The captain shifted deeper into his chair, took out a handkerchief and wiped his neck. “Smart punk,” he said. He turned to the sergeant for confirmation. “Smart punk, huh?”

The sergeant nodded.

“All right, smart punk,” the captain murmured, “let’s see how tough you really are.” He turned back to the sergeant. “See what he thinks of the Hole.”

CHAPTER TEN

The Hole was a small cell, bare of any but the most essential features, and it hadn’t been cleaned in a long time. The inside of the toilet was stained a deep orange below the waterline and the pipes banged and hissed before a brownish trickle would run in the sink. The only light was a forty-watt bulb, recessed into the ceiling and protected by a grate of woven metal strips. A bare mattress covering half the floor space was so old almost all of the cotton tufts were missing; the few remaining were a dark gray. The single blanket felt greasy. The only other object in the cell was a Gideon Bible. The cover was missing and the pages torn out into the middle of Exodus.

The walls were the original brick of the building, repainted many times, and now almost completely covered with a jumble of names, dates, and initials, the work of men intent on leaving their record, as before them more powerful men had caused mountains of stone to be built in the desert. During the first few hours, Doug read these brief and sometimes tragic histories. Many of the dates preceded his own birth, and it gave him an eerie feeling to think of men being in this hole before he was even born, carving the evidence of their passing into the submerged brick. A. Lundgren. Going to hang for something he never done. The lettering was as neat and compressed as a bookkeeper’s entry. THE TUCSON KID was deeply scored in large jagged capitals, dwindling off towards the floor as the carver tired and lost his enthusiasm for immortality.

Doug would have added his own name—he thought of calling himself “The Portland Kid”—but he didn’t have anything to scratch with. He could have used the tongue of his belt buckle, but the sergeant had taken his belt as well as his shoestrings. Afraid he’d hang himself. But that was silly because there wasn’t anything to hang from.

There was nothing to do. He tried walking back and forth, but his shoes flopped without laces, and even when he kicked them off he still had to keep his hands in his pockets or his pants would slip down. He picked up the Bible and stared at the close print, but the unfamiliar syntax threw him off and he sailed it into the corner, much the same as he’d thrown his school books away. What he needed to know wasn’t in books, or if it was, it meant nothing that way.

Later, the door opened and some dinner was shoved in by a khaki arm, obviously some beans left over from lunch, served on a paper plate with a tiny wooden picnic fork. After he ate the beans, he tried to scratch the brick with the fork, but the wood wore away faster than the wall.

He settled on the mattress with his jacket under his head and tried to feel sleepy. But he wasn’t, so he stared at the light until his eyes smarted, then when he closed them the inside of his eyelids would flare with small suns, spinning on velvet until they looked like the skirts of dancers, hanging feet-down out of the sky, spinning and blurring into one another; and then shifting and stretching until they became bars of violet light, spread out like the rills of the desert after the sun has just set; thickening and darkening until they caged the vision of his inner eye.

Even before he started running away, Doug’s life had been an endless series of moves, always moving to new places, and then in a few months moving on. His father was a heavy-construction worker, and he followed the jobs. Wherever the tunnels were going in, wherever they were building bridges or dams, that’s where they lived—sometimes in the country, sometimes in towns or cities.

His earliest memories were tied up with the smell and the feeling of furnished rooms, and the uncertainty of strange neighborhoods where he stood around in the city streets or the dirt lanes formed by tarpaper construction shacks, hoping the other kids would invite him to play their games. He never developed any special skills with which to win friendship or recognition; he played an average game of marbles, stickball, and kick-the-can. When teams were being chosen for baseball or football he was always picked close to the last, just before the little kids and the hopelessly bad players. He was never a secure member of the little neighborhood groups. If there was a quarter to be spent at the fountain, somehow he was left out, as he was left off the lists mothers made up for parties, mostly because they didn’t know him too well, and his manner was quiet.

In school it was much the same. He was below-average as a student, not because he was dumb, but because for months at a time he was out of school altogether, and because so many different teachers and methods had filled his mind with a disorganized jumble. He might leave one school just as they were starting long division and enter the next just as they were completing it, and he had to struggle to catch up.

His memories of school were hopelessly linked with the agony of standing before a classroom of judging strangers, while the teacher introduced him and found him a seat. That and the humiliation of handing his father a report card full of Ds and Cs. “Hell, kid, can’t you do any better than that? Do you want to end up a construction stiff like me?”

His father’s thick hair was permanently ridged by the band inside his metal safety helmet, and while his lower face was weathered red by the sun and the wind, his forehead, protected by the hat brim, was a naked white. He seemed incomplete without a hat. He was that kind of man.

Away from him, Doug could admit that his father worked hard, that he was a good builder, but this admission did nothing to kill the years of bitter envy when he’d wished that his father was a clerk in a store, the same store year after year. Yet he knew that wouldn’t have been enough to make up for all the mothers he’d had, not that he’d minded most of them—they came and went too—but the thing he hated was that now he couldn’t separate his own mother from all the other images, the women who had minded him, dressed him and scolded him. Their different faces blurred in his mind, and it seemed that if he couldn’t separate that one special face, his life would never mean anything. Yet at other times this loss didn’t affect him, and he didn’t think about it.

For a short time he’d been with a gang of kids who stole bottles for the deposits, taking them from garages or back porches and redeeming them at the local grocery for candy or show money. When his father moved on, going to another job site, Doug took the trick with him, and after awhile he worked off the back porches into the houses, and finally into stores. He never took much money because it frightened him to have it; he took enough for shoes and sodas and second-hand adventure magazines, and sometimes he tried to stand treat, but somehow he didn’t do it right because the others didn’t change towards him for any longer than it took to gobble up his gifts.

At times he thought he was happiest alone in the night, a nameless shadow. There was a funny kind of power in it, almost like being invisible. He would lay on a roof for hours, resting his chin on the damp tarpaper, watching the car lights and the people moving in the street below him, and then it seemed better to be out of it, an unmoved observer hanging above the city, able to take what he wanted when he wanted it. When he climbed back down to the sidewalk, ready to go home, the contrast was so sharp that he could feel himself shrinking to the world’s measure of him—a shy kid who couldn’t talk very well or dance very well or do anything very well. He didn’t want to be that kid.

He thought he could change by running away, taking his life into his own hands, and after several false starts he’d been able to force himself to the decision in the city of Portland. A bad report card had helped; it was in the books he’d pitched into the gulch. He’d thrown all his former life into that gulch and started off with thirty-five cents and the clothes he had on, sure that he would find a way to make it all different. But he’d only wandered into a deeper isolation—shut off from children and not yet an adult, and without the power to break the walls of his shyness.

Until he entered the jail….

A jailer pulled him out in the morning, and he thought he was going back to the tank until he saw Terrel waiting for him in the booking room. He’d forgotten about the ring and he hated to walk into the booking room and face the position he’d put himself into.

But Terrel told him he was going down to court and he’d better comb his hair. They found him a comb in one of the drawers behind the booking desk, and he ran it through his hair, looking around for Bailey Johnson, but he wasn’t there. Doug relaxed. He started to hand the comb back, but the jailer told him to keep it.

The courtroom was on one of the lower floors and it wasn’t what Doug had expected from the movie courtrooms he’d seen. It was a narrow bare room like a country meeting hall, with wooden chairs and sterile white plaster; there were flags on either side of the judge’s bench and a Latin motto painted on the wall behind it. A few people were sitting in the chairs and some more were gathered around the bench talking quietly. When the judge came in they put their cigarettes out and fell silent.

“Arraignment,” Terrel told him quietly, but that didn’t mean anything to Doug. They sat down to wait, and he slumped in his chair, wondering if they’d put him back into the tank. He wanted to tell Agnes about the captain.

Doug recognized another man from the tank a few rows in front of them, the tall, dark-haired man who’d been playing poker. Pesco, Agnes had called him. Doug could only see the side of his face, but he seemed subdued, and much different than he had in the tank. When he stood up to approach the bench, Doug saw that he was handcuffed, and the bailiff waited until he was in front of the judge before he took the cuffs off.

Terrel nudged Doug. “Take a good look at that fellow, because if you keep on you’ll end up like him. He’s got so many charges against him he couldn’t do them all if he lived to be eight hundred years old.”

Pesco had his hands behind his back, rubbing his wrists, while the judge looked down at him like an angry sparrow. The judge read the charges and Pesco seemed smaller standing below him listening, but when the judge was finished, Pesco cleared his throat and said, “Not guilty.”

Terrel shook his head. “There isn’t anything you can do for a guy like that.”

But Doug had already made up his mind that he was going to enter the same plea—not guilty.

He wasn’t given the chance. The judge wouldn’t accept a plea from him until he’d been advised by counsel, and after he’d determined that Doug had no money he assigned him a public defender. Terrel told him the lawyer would come up and see him in a day or two.

Back in the booking room he found that the captain had left orders to let him out of the Hole in the morning. While the jailer waited to take him back up to the felony tank, Terrel pulled him aside and warned him about the ring. Terrel put it all on Bailey Johnson, how P.O.’d Johnson would be if Doug didn’t come up with the ring and any other stuff he had hidden, and despite what Agnes had told him, Doug was still frightened. He couldn’t help it, and nothing he could find to tell himself helped at all. He looked at the floor, shuffled his feet and said, “Yes, sir,” letting Terrel think that he was ready to do whatever they wanted. And what would he tell them tomorrow? Tomorrow it would be much worse. But maybe they wouldn’t come. Even as he thought that, he knew he was lying to himself.

But Terrel was pleased. He brought a quarter out of his pocket. “Here. Buy yourself something to eat when the commissary comes.”

Agnes was up; Doug saw him as he entered the tank, lounging against the bars, combing his hair and talking to Pesco. Agnes hailed him. “Hey, buddy!” Grinning and coming towards him. Pesco turned and looked out through the bars towards the window, frowning.

“Damn, buddy, you had me worried. What’d you do? Make the Hole?”

Agnes had a towel around his neck and he was barefoot. His hair was still damp from a shower. Doug sensed that Agnes was more glad than relieved to see him, and he smiled back.

“That’s right. I was in the Hole.”

“You must have talked pretty sassy to that old captain.”

“I didn’t tell him anything. I know that much.”

Agnes laughed. “I know damn well you didn’t. About an hour after they pulled you out, the gang of them came pounding up the stairs like a bunch of hippos. They went through things some, but they didn’t find anything.”

“I didn’t tell him anything.”

“I know you didn’t, buddy-loo, Pesco tells me they had you down at court.”

“It was nothing. Something about an arraignment. But all they did was give me a lawyer.”

Agnes dropped back a step and looked at him, studying, his blue eyes full of something like thought. He adjusted the towel on his neck as if it were a scarf. Doug felt a wash of misery, certain that Agnes had penetrated his lies.

But Agnes just punched him on the forearm with the side of his fist, lightly, a friendly gesture.

“That don’t look too good. They must think they have you solid. Maybe you left fingerprints or something. Did you think of that?”

“No. Maybe it was fingerprints.”

Agnes looked solemn. “Fingerprints are just like leaving your name for them to find.”

“It was probably my fingerprints.”

“Yeah.” Agnes punched him again. “Let’s walk.”

They went back and forth between the poker game and the tank door, back and forth in the thick air and the solid hard light of the tank, passing the same faces looking out of the empty cream walls. Doug saw Carl watching him from the doorway of their cell, but he pretended not to notice.

Agnes was leading up to something, and Doug was content to let him talk. He noticed with surprise that he was taller than Agnes; he was looking down into Agnes’s face, and there was nothing in Agnes’s eyes but friendship and a growing excitement. He began to whisper.

“You know what we’re planning? Well, I talked to Billy, and we’d like to have you along, but we didn’t think you were in enough trouble to have to go that rawjaw, but the way it looks— Well, what do you think?”

It took Doug strangely. He couldn’t imagine why they’d want him. “When are you going to try it?” he asked.

Agnes waited until another man walked past them, then he whispered, “Maybe tonight.”

So soon. Doug’s belly was icy with the thought, but then he realized that if Agnes said they could make it, they could. All he had to do was say yes. He saw a sudden blurred picture of himself and Agnes—maybe even Billy—traveling around the country, stealing what they needed. It would be fine. Terrel could whistle for that ring, and he would never see Bailey Johnson again. He wouldn’t have Carl looking at him in that funny way.

He said, “Sure, I’ll be glad to go.”

Agnes shook his hand. “I knew you’d go for it.” He ran to the cell, and Billy came out, rubbing the side of his face. He smiled at Doug too, when Agnes told him. “The more the merrier,” he said. “It’s your secret too, now.”

“We didn’t have to worry about him. You got a right to go, Doug. You’re helping to pay for the blades. I didn’t know who you were then. You know what I mean?”

Doug knew Agnes was talking about his watch, but that didn’t matter now. He didn’t need it.

They settled down in a corner and began to talk plans, and Doug felt the excitement squeezing out of him; he shifted his feet and banged his hands together and he wanted to laugh out loud, or shout or something.

Agnes laid it out: Slim was going to bring the blades at noon, and they’d saw out that night. Agnes paused and touched Doug on the arm. “We’ll handle all that, but after we get out then you can take over. We’re going to need some money fast, from somewhere right here in town, and—”

Doug continued to nod his head, but he couldn’t keep smiling. It didn’t surprise him that that was the reason they wanted him—he should have expected it—but it was just that he wished he really had some money. He didn’t mind them wanting it, only now they would find him out for sure. He started smiling again, feeling like a phony.

When the tempo of the talk died down, Doug asked Agnes what he thought had happened to his cup. Agnes shrugged. “Damned if I know, buddy.”

CHAPTER ELEVEN

Slim was having trouble making up his mind. He spent some of the morning laying on his bunk in the trusty dormitory. In Slim’s mind the whole jail was laid out as precisely as a floor plan, because he’d tried to devise an escape of his own and abandoned it as hopeless. Now he tried to guess what Agnes had in mind, wondering if Agnes had found something he had overlooked. There were sometimes holes so obvious that no one thought of them. Slim remembered the jail they’d put up in Kansas. For six months they’d boasted about how escape-proof it was going to be, and yet the very week they’d opened it someone had wandered out with as much effort as it took to go down to the corner for a beer. Remembering this, Slim had some second thoughts about Agnes. He thought of the two metal doors between the booking room and the tank. There was no way through them, and even if there were, they wouldn’t have a chance to make it onto the elevator, and that was the only way down from the jail. Even in the tank itself it seemed hopeless, because if they could manage to get out, they still had the bars to saw out of the window, and the patrol would pick them up before they could get started. No. He didn’t have to worry about them making it.