Escape Plus, page 1

Ben Bova

TOR

A TOM DOHERTY ASSOCIATES BOOK

This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this book are fictional, and any resemblance lo real people of incidents is purely coincidental.Escape!, © 1970 by Ben Bova.

A Slight Miscalculation, © 1971 by Mercury Press, Inc.; 1973 by Ben Bova

Vince's Dragon, © 1981 by Ben Bova.

The Last Decision, © 1978 by Random House, Inc.

Men of Good Will, © 1964 by Galaxy Publishing Corporation; 1973 by Ben Bova.

Blood of Tyrants, © 1970 by Ultimate Publishing Co.; 1973 by Ben Bova

The Next Logical Step, © 1962 by The Condé Nast Publications, Inc.; 1973 by Ben Bova.

The Shining Ones, © 1975 by Ben Bova.

Sword Play, © 1975 by the Boy Scouts of America.

A Long Way Back, © 1960 by Ziff-Davis Publishing Co.

Stars, Won't You Hide Me?, © 1966 by Galaxy Publishing Corporation; 1973 by Ben Bova.

ESCAPE PLUS

Copyright © 1984 by Ben Bova

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form.

A TOR Book

Published by Tom Doherty Associates, Inc.

49 West 24 Street

New York, N.Y 10010

First Tor printing: December 1984

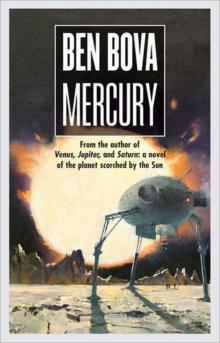

Cover art by Joe Bergeron

ISBN; 0-812-53212-0

CAN. ED.: 0-812-53213-

This book is dedicated to my Number-One Fan and good friend, David Rosenfield.

Contents

Forecast: The Worlds ModelerEscape!

A Slight Miscalculation

Vince's Dragon

The Last Decision

Men of Good Will

Blood of Tyrants

The Next Logical Step

The Shining Ones

Sword Play

A Long Way Back

Stars, Won't You Hide Me?

FORECAST: THE WORLDS MODELER

It is called FORECASTS. It was created for the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the generals and admiral who head the U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps. It has cost more than a million dollars to develop, and will cost still more before it is fully tested and operational.FORECASTS is a computer model of the whole world. It is a highly complex program that contains enormous amounts of data about global political trends, natural resources, and social and economic factors, The Joint Chiefs will use FORECASTS to help them make the predictions that go into their Joint Long Range Strategic Appraisal, in which the JCS evaluate what the world in general, and certain nations in particular, will look like over the next thirty years.

Science fiction writers have been making such predictions for generations now, and because the accuracy of the forecast is only as good as the quality of the information being used, the predictions of science fiction writers have generally been better than those of anyone else's—including the complex computerized "world models" of the scientists who call themselves futurists.

For example, futurists such as the late Herman Kahn have consistently missed the major turning points in recent history. No futurist predicted the Arab oil embargo of and the resulting panic of the energy crises which depressed the economies of the industrialized nations for a decade. The Club of Rome's much-heralded study, The Limits to Growth, failed utterly to understand that the Earth is not the only body in the universe from which the human race can extract energy and natural resources. The Presidential commission which produced Report on the Year 2000 was equally medieval in its view, and failed even to see the vigorous growth of living standards in the small industrializing nations of the Far East, nations such as Taiwan, South Korea, Malaysia, and Singapore.

Science fiction's record of predicting the future is much better. Atomic power, space flight, organ transplants, population explosions, the changes in social mores that we now call "the sexual revolution," genetic engineering—all these changes in human capabilities were described in science fiction stories at least thirty years before they took place in reality. What is more important, science fiction writers also predicted the social consequences of such changes: the Cold War stalemate that has resulted from atomic weapons; the urban sprawl that came from increased mobility and growing population; the breakdown of traditional family values and morality that has accompanied the new sexual freedoms.

Why is it that science fiction writers have seen farther into the future than all others—and more clearly? Is it because they are trained in the sciences? Hardly. Although many writers of science fiction have degrees in the physical or social sciences, very few of them are actually practicing scientists. Isaac Asimov, for example, has not engaged in scientific research for nearly three decades, despite his doctorate in chemistry and his title of professor of biochemistry at Boston University School of Medicine. Ray Bradbury, on the other hand, has no scientific training at all. Yet both Asimov and Bradbury are world-class science fiction writers, and both have graced the literature with scores of powerful and predictive stories.

The thing that makes a science fiction writer better at predicting the future than anyone else is not scientific knowledge, although an understanding of science is very helpful, even necessary. Nor is it a mystical, arcane extrasensory perception of the future. No writer that I know of claims to be in contact with the Spirit of Christmas Yet To Come.

The science fiction writer's secret can be told in two words: freedom and imagination.

The professional scientists who try to predict the future with computerized accuracy always fail because they are required to stick to the facts. No futurist is going to predict that a semi-accidental discovery will transform the entire world. Yet the invention of the transistor did just that: without the transistor and its microchip descendants, today's world of computers and communications satellites simply would not exist. Yet a futurist's forecast of improvements in electronics technology, made around 1950, would have concentrated on bigger and more complicated vacuum tubes and missed entirely the microminiaturization that transistors have made possible. Science fiction writers, circa 1950, "predicted" marvels such as wrist-radios and pocket-sized computers, not because they foresaw the invention of the transistor but because they intuitively felt that some kind of improvement would come along to shrink the bulky computers and radios of that day.

The professional futurists labor under this enormous handicap; they are not allowed to consider the "wild cards," the crazy things that can and usually do happen. They are restricted to making more-or-less straight-line extrapolations of the facts as we know them today. Science fiction writers have the freedom to use more than the facts. They can use their imaginations. They can ask themselves, "What would happen if…?" and then set out to write a story that answers the question. They can use their knowledge of the human soul—for that is what fiction is all about—not merely to describe the marvelous invention or the strange discovery, but to portray how real people—you or I—might react to these new things.

That is science fiction's great advantage, the freedom to employ human imagination to its fullest. The science fiction writer is not required to be accurate, merely entertaining. Although the writer need not have a professional knowledge of science, he or she should understand the basics well enough to know what is impossible—and how to move at least one step beyond that limit. The rule of thumb in good science fiction is that you are free to invent anything you like, providing no one else can prove that it could never be. Even though physicists are certain that nothing in the universe travels faster than the speed of light, they cannot prove that it is utterly impossible for a starship to circumvent that speed limit; therefore science fiction writers can create interstellar dramas, with merely a slight bow to acknowledge that their faster-than-light starships are using principles that were unknown in the 20th century. In creating such stories about some future times and places, the writer often creates an inner reality that eventually comes true.

You don't need a million-dollar computer program or a team of Pentagon scientists. All you need is that strange and elusive quality called talent, plus the fortitude to work long and lonely hours, together with the freedom to let your imagination roam where it will.

The stories in this collection are examples of how my imagination and creative freedom has led me to build worlds that do not exist—yet. From an electronically guarded prison that could be built today to the farthest ultimate reaches of interstellar space, these stories present eleven different answers to eleven different phrasings of that question, "What would happen if…?" One of these tales, The Next Logical Step, deals with the kind of computer that the Joint Chiefs of Staff might find themselves facing soon. Another, A Long Way Back, was my very first published short story; it dealt, in a way, with the basic factors of both the energy crisis that erupted a dozen years after the story was published and the aftermath of a nuclear war—a subject very much in the forefront of everyone's thinking even today, a quarter-century after the story was written.

Two of these tales are not really science fiction. One of them is a fantasy about a dragon, and the other is a "straight" story about my favorite sport, fencing. Both of them come directly from experiences in my younger years in South Philadelphia, that heartland of pop singers, steak sandwiches, and Rocky Balboa.

None of these tales has "come true" as yet, but that is not important. Each of them examines a reality of its own. Each of them places real people in strange and challenging situations. Each of them tests the human spirit in o

Ben Bova

West Hartford, Connecticut

ESCAPE!

We tell ourselves a lot of lies about prisons. The biggest lie is calling it "the criminal justice system;" it is not a system, it has nothing to do with justice, and if there is anything criminal about it, it's the fact that jails tend to make their inmates lifelong antisocial animals.I started my writing career on newspapers, and spent a lot of those early years covering the police beat in an upper-middle-class suburban area outside my native Philadelphia. As an investigative reporter (we didn't know that term back in the Fifties, we just called it legwork) I spent a summer probing into the problem of juvenile crime. The eventual result was Escape!, which was published originally as a short novel.

Two other factors went into writing this story; both involved the idea of a "perfect" jail. One was the notion that the lure of escape was the only thing that kept most inmates alive, especially the ones with long or indeterminate sentences. I read somewhere about a prison chaplain saying that if the inmates truly believed that they could never possibly escape from the jail they were in, they would go insane or commit suicide. The other factor was the kind of idea that only a science fiction writer would think of: suppose we made a jail that is as good as we can possibly imagine, a jail that actually works the way we good citizens say we want our jails to work, a jail that helps its inmates to become honest, upright, tax-paying citizens.

The result was the campus-like and absolutely escape-proof prison in Escape!, with its electronic sentries and all-seeing computer, SPECS. But to make the prison work the way I wanted it to, there had to be a human side to it. The machines can do only so much; the jail with its electronic marvels is merely a box in which to hold prisoners. To make the jail work in a way that would transform those prisoners into healthy, self-reliant, honest citizens required a human mind, a human soul, a human purpose. Thus Joe Tenny entered the equation, and became the main force in the resulting story.

Joe is modelled very closely on a man I knew and worked with for several years. The real "Joe Tenny" was a man of enormous talents and passions, a teacher, a scientist, a man who had worked himself too hard for his own good. He died much too early. The world is poorer for that. A pale shadow of him lives on in this story. That's not enough, but if this story shows you how we can use what's best in us to make the world better, then Joe's vital spark of life is not completely extinguished.

Escape!, incidentally, has generated more mail from readers than any other single story I have ever written. I credit "Joe Tenny's" indomitable spirit for that; he was the kind of man who made people feel good about themselves.

CHAPTER ONE

The door shut behind him.Danny Romano stood in the middle of the small room, every nerve tight. He listened for the click of the lock. Nothing.

Quiet as a cat, he tiptoed back to the door and tried the knob. It turned. The door was unlocked.

Danny opened the door a crack and peeked out into the hallway. Empty. The guards who had brought him here were gone. No voices. No footsteps. Down at the far end of the hall, up near the ceiling, was some sort of TV camera. A little red light glowed next to its lens.

He shut the door and leaned against it.

"Don't lem 'em sucker you," he said to himself. "This is a jail."

Danny looked all around the room. There was only one bed. On its bare mattress was a pile of clothes, bed sheets, towels and stuff. A TV screen was set into the wall at the end of the bed. On the other side of the room was a desk, an empty bookcase, and two stiff-back wooden chairs. Somebody had painted the walls a soft blue.

"This can't be a cell… not for me, anyway. They made a mistake."

The room was about the size of the jail cells they always put four guys into. Or sometimes six.

And there was something else funny about it. The smell, that's it! This room smelled clean. There was even fresh air blowing in through the open window. And there were no bars on the window. Danny tried to remember how many jail cells he had been in. Eight? Ten? They had all stunk like rotting garbage.

He went to the clothes on the bed. Slacks, real slacks. Sport shirts and turtlenecks. And colors! Blue, brown, tan. Danny yanked off the gray coveralls he had been wearing, and tried on a light blue turtleneck and dark brown slacks. They even fit right. Nobody had ever been able to find him a prison uniform small enough to fit his wiry frame before this.

Then he crossed to the window and looked outside. He was on the fifth or sixth floor, he guessed. The grounds around the building were starting to turn green with the first touch of early spring. There were still a few patches of snow here and there, in the shadows cast by the other buildings.

There were a dozen buildings, all big and square and new-looking. Ten floors high, each of them, although there were a couple of smaller buildings farther out. One of them had a tall smokestack. The buildings were arranged around a big, open lawn that had cement paths through it. A few young trees lined the walkways. They were just beginning to bud.

"No fences," Danny said to himself.

None of the windows he could see had bars. Everyone seemed to enter or leave the buildings freely. No guards and no locks on the doors? Out past the farthest building was an area of trees. Danny knew from his trip in here, this morning, that beyond the woods was the highway that led back to the city.

Back to Laurie.

Danny smiled. What were the words the judge had used? In… in-de-ter-minate sentence. The lawyer had said that it meant he was going to stay in jail for as long as they wanted him to. A year, ten years, fifty years…

"I'll be out of here tonight!" He laughed.

A knock on the door made Danny jump. Somebody-heard me!

Another knock, louder this time. "Hey, you in there?" a man's voice called.

"Y… yeah."

The door popped open. "I'm supposed to talk with you and get you squared away. My name's Joe Tenny."

Joe was at least forty, Danny saw. He was stocky, tough-looking, but smiling. His face was broad; his dark hair combed straight back. He was a head taller than Danny and three times wider. The jacket of his suit looked tight across the middle. His tie was loosened, and his shirt collar unbuttoned.

A cop, Danny thought. Or maybe a guard. But why ain't he wearing a uniform?

Joe Tenny stuck out a heavy right hand. Danny didn't move.

"Listen, kid," Tenny said, "we're going to be stuck together for a long time. We might as well be friends."

"I got my own friends," said Danny. "On the outside."

Tenny's eyebrows went up while the corners of his mouth went down. His face seemed to say. Who are you trying to kid, wise guy?

Aloud, he said, "Okay, suit yourself. You can have it any way you like, hard or easy." He reached for one of the chairs and pulled it over near the bed.

"How long am I going to be here?"

"That depends on you. A couple of years, at least." Joe turned the chair around backwards and sat on it as if it were a saddle, leaning his stubby arms on the chair's back.

Danny swung at the pile of clothes and things on the bed, knocking most of them onto the floor. Then he plopped down on the mattress. The springs squeaked in complaint.

Joe looked hard at him, then let a smile crack his face. "I know just what's going through your mind. You're thinking that two years here in the Center is going to kill you, so you're going to crash out the first chance you get. Well, forget it! The Center is escape-proof."

In spite of himself, Danny laughed.

"I know, I know…" Tenny grinned back at him. "The Center looks more like a college campus than a jail. In fact, that's what most of the kids call it—the campus. But believe me, Alcatraz was easy compared to this place. We don't have many guards or fences, but we've got TV cameras, and laser alarms, and SPECS."

"Who's Specks?" Danny asked.

Joe called out, "SPECS, say hello."

The TV screen on the wall lit up. A flat, calm voice said, "GOOD MORNING DR. TENNY. GOOD MORNING MR, ROMANO. WELCOME TO THE JUVENILE HEALTH CENTER."

Danny felt totally confused. Somebody was talking through the TV set? The screen, though, showed the words he was hearing, spelled put a line at a time. But they moved too fast for Danny to really read them. And Specks, whoever he was, called Joe Tenny a doctor.