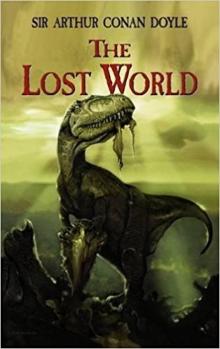

The Lost World, page 1

Produced by Judith Boss. HTML version by Al Haines.

THE LOST WORLD

I have wrought my simple plan If I give one hour of joy To the boy who's half a man, Or the man who's half a boy.

The Lost World

By

SIR ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

COPYRIGHT, 1912

Foreword

Mr. E. D. Malone desires to state that both the injunction for restraint and the libel action have been withdrawn unreservedly by Professor G. E. Challenger, who, being satisfied that no criticism or comment in this book is meant in an offensive spirit, has guaranteed that he will place no impediment to its publication and circulation.

Contents

CHAPTER

I. "THERE ARE HEROISMS ALL ROUND US" II. "TRY YOUR LUCK WITH PROFESSOR CHALLENGER" III. "HE IS A PERFECTLY IMPOSSIBLE PERSON" IV. "IT'S JUST THE VERY BIGGEST THING IN THE WORLD" V. "QUESTION!" VI. "I WAS THE FLAIL OF THE LORD" VII. "TO-MORROW WE DISAPPEAR INTO THE UNKNOWN" VIII. "THE OUTLYING PICKETS OF THE NEW WORLD" IX. "WHO COULD HAVE FORESEEN IT?" X. "THE MOST WONDERFUL THINGS HAVE HAPPENED" XI. "FOR ONCE I WAS THE HERO" XII. "IT WAS DREADFUL IN THE FOREST" XIII. "A SIGHT I SHALL NEVER FORGET" XIV. "THOSE WERE THE REAL CONQUESTS" XV. "OUR EYES HAVE SEEN GREAT WONDERS" XVI. "A PROCESSION! A PROCESSION!"

THE LOST WORLD

The Lost World

CHAPTER I

"There Are Heroisms All Round Us"

Mr. Hungerton, her father, really was the most tactless person uponearth,--a fluffy, feathery, untidy cockatoo of a man, perfectlygood-natured, but absolutely centered upon his own silly self. Ifanything could have driven me from Gladys, it would have been thethought of such a father-in-law. I am convinced that he reallybelieved in his heart that I came round to the Chestnuts three days aweek for the pleasure of his company, and very especially to hear hisviews upon bimetallism, a subject upon which he was by way of being anauthority.

For an hour or more that evening I listened to his monotonous chirrupabout bad money driving out good, the token value of silver, thedepreciation of the rupee, and the true standards of exchange.

"Suppose," he cried with feeble violence, "that all the debts in theworld were called up simultaneously, and immediate payment insistedupon,--what under our present conditions would happen then?"

I gave the self-evident answer that I should be a ruined man, uponwhich he jumped from his chair, reproved me for my habitual levity,which made it impossible for him to discuss any reasonable subject inmy presence, and bounced off out of the room to dress for a Masonicmeeting.

At last I was alone with Gladys, and the moment of Fate had come! Allthat evening I had felt like the soldier who awaits the signal whichwill send him on a forlorn hope; hope of victory and fear of repulsealternating in his mind.

She sat with that proud, delicate profile of hers outlined against thered curtain. How beautiful she was! And yet how aloof! We had beenfriends, quite good friends; but never could I get beyond the samecomradeship which I might have established with one of myfellow-reporters upon the Gazette,--perfectly frank, perfectly kindly,and perfectly unsexual. My instincts are all against a woman being toofrank and at her ease with me. It is no compliment to a man. Wherethe real sex feeling begins, timidity and distrust are its companions,heritage from old wicked days when love and violence went often hand inhand. The bent head, the averted eye, the faltering voice, the wincingfigure--these, and not the unshrinking gaze and frank reply, are thetrue signals of passion. Even in my short life I had learned as muchas that--or had inherited it in that race memory which we call instinct.

Gladys was full of every womanly quality. Some judged her to be coldand hard; but such a thought was treason. That delicately bronzedskin, almost oriental in its coloring, that raven hair, the largeliquid eyes, the full but exquisite lips,--all the stigmata of passionwere there. But I was sadly conscious that up to now I had never foundthe secret of drawing it forth. However, come what might, I shouldhave done with suspense and bring matters to a head to-night. Shecould but refuse me, and better be a repulsed lover than an acceptedbrother.

So far my thoughts had carried me, and I was about to break the longand uneasy silence, when two critical, dark eyes looked round at me,and the proud head was shaken in smiling reproof. "I have apresentiment that you are going to propose, Ned. I do wish youwouldn't; for things are so much nicer as they are."

I drew my chair a little nearer. "Now, how did you know that I wasgoing to propose?" I asked in genuine wonder.

"Don't women always know? Do you suppose any woman in the world wasever taken unawares? But--oh, Ned, our friendship has been so good andso pleasant! What a pity to spoil it! Don't you feel how splendid itis that a young man and a young woman should be able to talk face toface as we have talked?"

"I don't know, Gladys. You see, I can talk face to face with--with thestation-master." I can't imagine how that official came into thematter; but in he trotted, and set us both laughing. "That does notsatisfy me in the least. I want my arms round you, and your head on mybreast, and--oh, Gladys, I want----"

She had sprung from her chair, as she saw signs that I proposed todemonstrate some of my wants. "You've spoiled everything, Ned," shesaid. "It's all so beautiful and natural until this kind of thingcomes in! It is such a pity! Why can't you control yourself?"

"I didn't invent it," I pleaded. "It's nature. It's love."

"Well, perhaps if both love, it may be different. I have never feltit."

"But you must--you, with your beauty, with your soul! Oh, Gladys, youwere made for love! You must love!"

"One must wait till it comes."

"But why can't you love me, Gladys? Is it my appearance, or what?"

She did unbend a little. She put forward a hand--such a gracious,stooping attitude it was--and she pressed back my head. Then shelooked into my upturned face with a very wistful smile.

"No it isn't that," she said at last. "You're not a conceited boy bynature, and so I can safely tell you it is not that. It's deeper."

"My character?"

She nodded severely.

"What can I do to mend it? Do sit down and talk it over. No, really,I won't if you'll only sit down!"

She looked at me with a wondering distrust which was much more to mymind than her whole-hearted confidence. How primitive and bestial itlooks when you put it down in black and white!--and perhaps after allit is only a feeling peculiar to myself. Anyhow, she sat down.

"Now tell me what's amiss with me?"

"I'm in love with somebody else," said she.

It was my turn to jump out of my chair.

"It's nobody in particular," she explained, laughing at the expressionof my face: "only an ideal. I've never met the kind of man I mean."

"Tell me about him. What does he look like?"

"Oh, he might look very much like you."

"How dear of you to say that! Well, what is it that he does that Idon't do? Just say the word,--teetotal, vegetarian, aeronaut,theosophist, superman. I'll have a try at it, Gladys, if you will onlygive me an idea what would please you."

She laughed at the elasticity of my character. "Well, in the firstplace, I don't think my ideal would speak like that," said she. "Hewould be a harder, sterner man, not so ready to adapt himself to asilly girl's whim. But, above all, he must be a man who could do, whocould act, who could look Death in the face and have no fear of him, aman of great deeds and strange experiences. It is never a man that Ishould love, but always the glories he had won; for they would bereflected upon me. Think of Richard Burton! When I read his wife'slife of him I could so understand her love! And Lady Stanley! Did youever read the wonderful last chapter of that book about her husband?These are the sort of men that a woman could worship with all her soul,and yet be the greater, not the less, on account of her love, honoredby all the world as the inspirer of noble deeds."

She looked so beautiful in her enthusiasm that I nearly brought downthe whole level of the interview. I gripped myself hard, and went onwith the argument.

"We can't all be Stanleys and Burtons," said I; "besides, we don't getthe chance,--at least, I never had the chance. If I did, I should tryto take it."

"But chances are all around you. It is the mark of the kind of man Imean that he makes his own chances. You can't hold him back. I'venever met him, and yet I seem to know him so well. There are heroismsall round us waiting to be done. It's for men to do them, and forwomen to reserve their love as a reward for such men. Look at thatyoung Frenchman who went up last week in a balloon. It was blowing agale of wind; but because he was announced to go he insisted onstarting. The wind blew him fifteen hundred miles in twenty-fourhours, and he fell in the middle of Russia. That was the kind of man Imean. Think of the woman he loved, and how other women must haveenvied her! That's what I should like to be,--envied for my man."

"I'd have done it to please you."

"But you shouldn't do it merely to please me. You should do it becauseyou can't help yourself, because it's natural to you, because the manin you is crying out for heroic expr

"I did."

"You never said so."

"There was nothing worth bucking about."

"I didn't know." She looked at me with rather more interest. "Thatwas brave of you."

"I had to. If you want to write good copy, you must be where thethings are."

"What a prosaic motive! It seems to take all the romance out of it.But, still, whatever your motive, I am glad that you went down thatmine." She gave me her hand; but with such sweetness and dignity thatI could only stoop and kiss it. "I dare say I am merely a foolishwoman with a young girl's fancies. And yet it is so real with me, soentirely part of my very self, that I cannot help acting upon it. If Imarry, I do want to marry a famous man!"

"Why should you not?" I cried. "It is women like you who brace men up.Give me a chance, and see if I will take it! Besides, as you say, menought to MAKE their own chances, and not wait until they are given.Look at Clive--just a clerk, and he conquered India! By George! I'lldo something in the world yet!"

She laughed at my sudden Irish effervescence. "Why not?" she said."You have everything a man could have,--youth, health, strength,education, energy. I was sorry you spoke. And now I am glad--soglad--if it wakens these thoughts in you!"

"And if I do----"

Her dear hand rested like warm velvet upon my lips. "Not another word,Sir! You should have been at the office for evening duty half an hourago; only I hadn't the heart to remind you. Some day, perhaps, whenyou have won your place in the world, we shall talk it over again."

And so it was that I found myself that foggy November evening pursuingthe Camberwell tram with my heart glowing within me, and with the eagerdetermination that not another day should elapse before I should findsome deed which was worthy of my lady. But who--who in all this wideworld could ever have imagined the incredible shape which that deed wasto take, or the strange steps by which I was led to the doing of it?

And, after all, this opening chapter will seem to the reader to havenothing to do with my narrative; and yet there would have been nonarrative without it, for it is only when a man goes out into the worldwith the thought that there are heroisms all round him, and with thedesire all alive in his heart to follow any which may come within sightof him, that he breaks away as I did from the life he knows, andventures forth into the wonderful mystic twilight land where lie thegreat adventures and the great rewards. Behold me, then, at the officeof the Daily Gazette, on the staff of which I was a most insignificantunit, with the settled determination that very night, if possible, tofind the quest which should be worthy of my Gladys! Was it hardness,was it selfishness, that she should ask me to risk my life for her ownglorification? Such thoughts may come to middle age; but never toardent three-and-twenty in the fever of his first love.