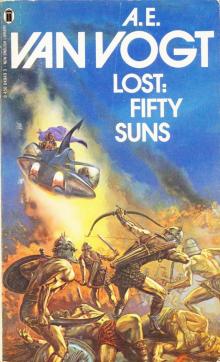

Lost-Fifty Suns, page 1

LOST: FIFTY SUNS

by

A. E. van Vogt

NEW ENGLISH LIBRARY

NEL Books are published by New English Library Limited,

Barnard’s Inn, Ho!born,

London EC IN 2JR,

Le Scrob

Contents

THE TIMED CLOCK 7

THE CONFESSION 21

THE RAT AND THE SNAKE 37

THE BARBARIAN 41

ERSATZ ETERNAL 80

THE SOUND OF WILD LAUGHTER 85

LOST: FIFTY SUNS 138

The Timed Clock

‘Marriage,’ Terry Maynard will say when he’s feeling expansive, ‘is a sacred institution. I ought to know. I’ve been married twice, once back in 1905, and again in 1967. That kind of time interval gives a man perspective for a fair judgment.’

And having said that, he looks blandly over at his wife Joan. She sighed on this particular evening, lit a cigarette, leaned back, and murmured, ‘Terry, you mad daredevil, you. Again?’

She sipped at her cocktail, looked with guileless blue eyes at the visitors, and said, ‘Terry is going to tell you the story of our romance. If you’ve heard it before, you’ll find sandwiches and things in the dining room.’

Two men and a woman got up and walked out. Terry called after them: ‘People laughed at the atomic bomb

- till it dropped on them. One of these days, somebody is going to find out I’m not just romancing. That what I say happened did happen and that it could happen to them. When I think of the deadly potentialities, the atomic bomb will look like a sputtering candle.’

One of the men in the group that had remained said in a puzzled tone, ‘I don’t get that. What can your being married in 1905 as well as now have to do with the A-bomb - entirely aside from the annoyance your charming wife may feel at not being able to sink those long fingernails of hers into the fair skin of her ancient rival?’ ‘Sir,’ said Terry, ‘you are speaking of my first wife - may she rest in peace.’

‘She never will,’ aid Joan Maynard. ‘Not if I can help it.’

But she settled herself comfortably. ‘Go on, Terry, darling,’ she said cozily.

‘When I was ten years old,’ began her husband, ‘I used to be fascinated by the old grandfather clock in the hall -you can all look at it on your way out. One day, I opened the door at the bottom, and I was playing with the pendulum when I saw it was marked with numbers. They started near the top of the long bar, and the first number was 1840, and they went right down to the bottom, and the last number was 1970. That was in 1950, and I remember being surprised that the little indicator on the crystalline weight pointed exactly at 1950. I thought I had made a great discovery about how clocks worked. After I got over my excitement, I began, of course, to fool around with the weight, and I recall sliding it up to 1891.

‘At that moment, I had a dizzy spell. I let go of the weight and sagged to the floor, feeling quite ill. When I looked up, there was a strange woman, and everything around me looked different. You understand, it was only a matter of furniture and rug arrangement. This house has been in our family for well over a hundred years.

‘But at ten I was instantly scared, particularly when I saw this woman. She was about forty years old. She wore an old-fashioned long skirt, her lips were pressed into a thin line of anger, and she held a switch in her hand. As I climbed shakily to my feet, she spoke: “Joe Maynard, how many times have I told you to stay away from that clock?”

‘Her calling me Joe froze me. I didn’t know then that my grandfather’s name was Joseph. Another thing that held me was her accent. Her English was quite precise; I can’t describe it. The third thing that paralyzed me was that in a vague kind of way her face began to look familiar. It was the face of my great-grandmother, whose portrait hung in my father’s study.

‘Swish! The switch caught me on one leg. I dived past her and headed for the door, yowling. I heard her calling after me: “Joe Maynard, you wait till your father comes home - ”

‘Outside, I was in fantasia, a primitive world in a small town in the late 1800s. A dog yipped after me. There were horses on the street, a wooden sidewalk. I had been brought up to dodge automobiles and ride on buses. I couldn’t take the change. My mind is blank about the hours that went by. But it grew dark, and I sneaked back to the big house and peered through the only lighted window into the dining room. I saw a sight I’ll never forget.

My great-grandfather and great-grandmother sat at dinner with a boy my own age; and that boy was practically my living image except that he looked more frightened than I ever hope to be. Great-grandfather was speaking: I could hear him plainly through the glass, he was so angry:

‘ “That settles it. Practically calling your own mother a liar. I’ll take care of you after dinner.”

‘I guessed Joe was getting it for me. But all that really mattered was that they were not in the hall near the clock.

I sneaked into the house, trembling and without really having a plan. I tiptoed over to the clock, opened the clock case, and set the weight back to 1950. I did that without thinking. My mind was like a block of ice.

‘The next thing I knew, a man was yelling at me. A familiar voice. When I looked around, it was my own dad. “You young wretch,” he shouted, “I thought I told you to stay away from that clock.”

‘For once a licking was a relief. But I never as a boy went near the clock again. I did get to the point where I asked cautiously about my ancestors. Dad was very reticent. He’d get a faraway look in his eyes, and he’d say, “I don’t understand a lot of things about my childhood, son. I'll tell you about it some day.”

‘He died suddenly of pneumonia when I was thirteen. It was a financial as well as emotional shock. Mother sold, among other things, the old grandfather clock; and we were thinking of transforming the old place into a rooming house, but a sudden industrial growth bcomed the value of some land we had on the other side of town. I had been thinking about the old clock and about my experience, but what with college and then my stint in Vietnam-I was what you might call a glorified office boy with the rank of captain -1 didn’t get a chance to look for it till early 1966. I traced it through the dealer who had bought it from us, and paid three times what we originally got for it, but of course it was worth it.

‘The weight on the pendulum had slipped down to 1966. The coincidence of that startled me. But more important, under a panel at the bottom I found a treasure: my grandfather’s diary.

‘The first entry was dated May 18, 1904. Kneeling there, grandfather’s diary in my hand, I naturally decided to make a test. Had my childhood experience been real, or had it been a delusion? I didn’t think then of actually arriving on the same day as the diary date, but I set it for 1904 as a matter of course. As a last-moment precaution, I slipped a .38 automatic into my coat pocket and then grasped the crystal weight.

‘It felt warm to the touch. I had the distinct feeling that it vibrated.

‘1 had no sense of nausea this time; and I was just about to give up, rather sheepishly, when I glanced around. The hall seat had been moved. The rugs were a darker variety. Old-fashioned drapes of heavy, dark velvet hung over the door.

‘My heart pounded. I worried about what I would say if I were discovered. Nevertheless, after a moment I realized that the house was silent except for the ticking of the clock. I stood up and in spite of what my eyes were seeing did not quite believe that the miracle had happened again.

‘I walked out into a town that had grown since I had seen it as a boy. But it was still early twentieth century. Cows in back yards. Chicken coops. In the near distance I could see open prairie. The real growth hadn’t begun, and there was no sign of the city that would someday be. It could easily be 1904.

‘In a haze of excitement, I walked along the wooden sidewalk. Twice, I passed people, a man, and then a woman. They looked at me in what I realize now was amazement, but I scarcely noticed them. It was not until two women approached me on the narrow sidewalk that I came out of my daze and realized that I was seeing flesh-and-blood people of the early 1900s.

‘They wore ground-length skirts that rustled. The day was warm. But it had evidently rained earlier, for I saw mud at the bottom of their skirts.

‘The older woman took one look at me and said, “Why, Joseph Maynard, so you’ve come home in time for your poor mother’s funeral. Where did you get those outlandish clothes?”

‘The girl said nothing. She just looked at me.

‘I was about to protest that I was not Joseph Maynard but realized it would be unwise to do so. Besides, I was remembering what the entry in grandfather’s diary had been for May eighteenth:

Met Mrs Caldwell and her daughter Marietta on the street. She couldn’t seem to get over my coming back for the funeral.

‘I thought, slightly dazzled, slightly blank, If this was Mrs Caldwell and her daughter, and this was that meeting, then -

‘The woman was speaking. “Joseph Maynard, I want you to meet my daughter Marietta. We were just speaking of the funeral, weren’t we, dear?”

‘The girl continued to look at me. “Were we, mother?” she asked.

‘ “Of course we were, don’t you remember?” Mrs Caldwell sounded flustered. She went on hastily. “Marietta and I are all ready for the funeral tomorrow.”

‘Marietta said calmly, “I thought you’d made arrangements to go to the Jones’ farm.”

‘ “Marietta, how can you say such a thing? That’s for the day after. If I’ve made any such arrangements, they

“ I always liked her,” said Marietta, with an ever so faint emphasis on the first-person pronoun.

“We’ll see you then tomorrow at the church at two o’clock,” Mrs Caldwell said quickly. “Come along, Marietta, darling.”

‘I drew back to let them pass, then walked around the block, back to the family home. I explored the house, half expecting to find a corpse, but evidently the body had been taken elsewhere.

‘I began to feel badly. My own mother had died in 1963 when I was far off in Vietnam. And our family lawyer had had to make the funeral arrangements. On many a hot night in the jungle I had pictured the silent house when she was ill. It seemed to me that this was about as close as I had gotten to the actuality. The parallel depressed me.

‘I locked the door, wound the clock, reset the weight to 1966, and returned to the twentieth century.

‘The somber atmosphere of death departed slowly, and I came back to a most worrying thought: Had Joseph Maynard really returned to his home town on May 18, 1904? And if not, to whom did the May nineteenth entry in grandfather’s diary refer? The diaiy entry stated simply:

Attended funeral this afternoon and talked again to Marietta.

‘Talked again! That’s what it said. And since it was I who had talked to her the first time, was it also I who would attend the funeral?

‘I spent the evening reading the diary, searching for a word or phrase that would indicate the situation was as I was beginning to see it. I did not find a single reference to time travel, but that seemed natural enough after I thought it over. Suppose the diary fell into the wrong hands.

‘I reached the entry where Joseph Maynard and Marietta Caldwell made their engagement announcement. And a little later I came to the date under which was written, “Married Marietta today! ” At that point, perspiring, I put the diary aside,

‘The question was, if it was I who had done that, then what had become of the real Joseph Maynard? Had the only son of my great-grandparents died on some American frontier, unknown to his fellow townsmen? From the beginning that seemed the most likely explanation.

‘I went to the funeral. And there was no doubt about it I was the only Maynard present, aside from my dead greatgrandmother.

‘Afterwards, I had a talk with the family lawyer, and I took formal possession of the property. I had him set up a trust for the land that fifty years later saved mother and me from having to become boarding-house keepers.

‘Then I set to work to insure that my father would be born.

‘Marietta was an amazingly difficult girl to marry for a man who knew that the marriage was a cinch. She had another suitor, a young fellow I could have strangled half a dozen times. He had a bubbling personality but no money. Her parents were down on him for that last, but it didn’t seem to worry Marietta.

‘In the end, because I couldn’t afford to lose, I played the game unfairly. I went to Mrs Caldwell and told her bluntly that I wanted her to start encouraging Marietta to marry this other guy and to start criticizing me. I suggested that she point out that I was not reliable and that at any time I was apt to go wandering off to some far corner of the world, taking her with me to heaven only knew what hardships.

‘As I had begun to suspect, that little girl had an adventurous streak in her. I don’t know just how much her mother was able to reverse her attitude, but suddenly Marietta was more friendly, I had become so intent on the courtship that I’d kind of forgotten about the diary. After we became engaged, I looked it up, and there it was written up exactly for the day it happened.

‘That gave me a grisly feeling. And when Marietta set the wedding day for the date given in the diary, I came even further out of my fantasy and in the most serious fashion considered my position. If I went through with this thing, then I would be my own grandfather. If I didn’t go through with it, then what?

‘Thinking about it just made me feel blank. But I looked around for a duplicate to the ancient leather diary, copied the old one word for word, and put the new one under the panel in the bottom of the clock. I suppose they were actually the same diary since the one I put in there must be the one I later found.

‘Marietta and I were married as scheduled, and it wasn’t long before we were able to guess that my father would be born in due course - though, naturally, Marietta didn’t think of it in that way.’

His account was interrupted. A woman said acidly, ‘Are we to understand, Mr Maynard, that you actually went through with the marriage and that that poor girl is now going to have a baby?’

Maynard said mildly, ‘All this happened back in the early 1900s.’

The woman’s color was high. ‘I think this is the most outrageous thing I have ever heard’

Maynard gazed quizzically at his audience. ‘How do the rest of you feel about this? Do you feel that a man hasn’t the moral right to insure that he be born?’

‘Well - ’ a man began doubtfully.

Maynard said, ‘Don’t you think I’d better finish the story before we talk?’

‘My troubles,’ he went on, ‘began almost immediately. Marietta wanted to know where I went to when I disappeared. She was damnably inquisitive about my past. Where had I been? What places had I visited? What made me leave home in the first place? Since I was not Joseph Maynard it wasn’t long before I felt like a hen-pecked husband. I had intended to stick with her at least until the baby was born, with only occasional journeys to the twentieth century. But she followed me around the house. Twice, she almost caught me using the clock. I grew alarmed; then I realized that Joseph Maynard would have to vanish again from his age, this time forever.

‘After all, what would be the point in my insuring my eventual birth if that was all I succeeded in doing? I had a life to live in 1967 and afterwards. There was even the problem of getting married again and having children who would carry on the line into the future.

‘In the end I made the break. There was nothing else to do.’

For a second time he was interrupted. ‘Mister Maynard,’ said the same woman who had previously spoken, ‘do you mean to sit there and tell us that you deserted that poor girl and her unborn baby?’

Maynard spread his hands helplessly. ‘What else? After all, she was well looked after. I even told myself that she might eventually marry the bubbling young man - though quite frankly I didn’t like the idea.’

‘Why didn’t you bring her up here?’

‘Because,’ said Terry Maynard, ‘I wanted the baby back there.'

The woman was white-faced and so angry that she stammered. ‘Mr Maynard, I don’t know whether I care to remain any longer under your roof.’

Maynard was astonished. ‘Madam, do you believe this story?’

She blinked at that and said, ‘Oh!’ Then she leaned back and laughed in an embarrassed fashion. Several people laughed at her, uncertainly.

Maynard went on. ‘You can’t imagine how guilty I felt. Every time I looked at a pretty girl the specter of Marietta would rise up before me. And I had a hard time convincing myself that she probably died somewhere in the 1940s or even earlier. And yet, after only four months, I couldn’t clearly remember what she looked like.

‘Then one night at a party I met Joan. She reminded me instantly of Marietta. And that was all I needed, I guess. I have to admit that she was the aggressor in the courtship. I was glad of that, however, as I’m not sure I would have taken the plunge if there hadn’t been someone like Joan pushing at me.

‘We were married, and as is the custom I carried her across the threshold of the old house. After I had set her down, she stood looking at me for a long time with the oddest expression on her face. At last she said in a low voice, “Terry, I have a confession to make.”

‘ “Yes?” I couldn’t imagine what it might be.

‘ “Terry, there’s a reason why I rushed you into this marriage.”

‘That gave me a sinking sensation. I had heard of girls marrying hastily for certain reasons.

“Terry, I’m going to have a baby.”

‘Having said that, she came over and slapped me 'in the face. I don’t think I’ve ever been more bewildered in my life.’